Despite recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) research, human

children are still by far the best learners we know of, learning impressive

skills like language and high-level reasoning from very little data. Children’s

learning is supported by highly efficient, hypothesis-driven exploration: in

fact, they explore so well that many machine learning researchers have been

inspired to put videos like the one below in their talks to motivate research

into exploration methods. However, because applying results from studies in

developmental psychology can be difficult, this video is often the extent to

which such research actually connects with human cognition.

A time-lapse of a baby playing with toys. Source.

Why is directly applying research from developmental psychology to problems in

AI so hard? For one, taking inspiration from developmental studies can be

difficult because the environments that human children and artificial agents

are typically studied in can be very different. Traditionally, reinforcement

learning (RL) research takes place in grid-world-like settings or other 2D

games, whereas children act in the real world which is rich and 3-dimensional.

Furthermore, comparisons between children and AI agents are difficult to make

because the experiments are not controlled and often have an objective

mismatch; much of the developmental psychology research with children takes

place with children engaged in free exploration, whereas a majority of research

in AI is goal-driven. Finally, it can be hard to ‘close the loop’, and not only

build agents inspired by children, but learn about human cognition from

outcomes in AI research. By studying children and artificial agents in the

same, controlled, 3D environment we can potentially alleviate many of these

problems above, and ultimately progress research in both AI and cognitive

science.

In collaboration with Jessica Hamrick and Sandy Huang from DeepMind, and Deepak

Pathak, Pulkit Agrawal, John Canny, Alexei A. Efros, Jeffrey Liu, and Alison Gopnik from UC Berkeley, that’s

exactly what this work aims to do. We have developed a platform and framework

for directly contrasting agent and child exploration based on DeepMind Lab – a

first person 3D navigation and puzzle-solving environment originally built for

testing agents in mazes with rich visuals.

What do we actually know about how children explore?

The main thing that we know about the child exploration is that children form

hypotheses about how the world works, and they engage in exploration to test

those hypotheses. For example, studies such as the one from Liz Bonawitz et

al., 2007 showed us that preschoolers’ exploratory play is affected by the

evidence they observe. They conclude that if it seems like there are multiple

ways that a toy could work but it’s not clear which one is right (in other

words, the evidence is causally confounded) then children engage in

hypothesis-driven exploration and will explore the toy for significantly longer

than when the dynamics and outcome are simple (in which case they would quickly

move on to a new toy).

Stahl and Feigneson et al., 2015 showed us that when babies as young as

11-months are presented with objects that violate physical laws in their

environments they will explore them more and even engage in hypothesis-testing

behaviors that reflect the particular kind of violation seen. For example, if

they see a car floating in the air (as in the video on the left), they find

this surprising; subsequently, children then bang the toy on the table to

explore how it works. In other words, these violations guide the children’s

exploration in a meaningful way.

How do AI agents explore?

Classic work in computer science and AI focused on developing search methods

that try to seek out a goal. For example, a depth-first search strategy will

continue exploring down a particular path until either the goal or a dead-end

is reached. If a dead-end is reached, it will backtrack until the next

unexplored path is found and then proceed down that path. However, unlike

children’s exploration, methods like these don’t have a notion of exploring

more given surprising evidence, gathering information, or testing hypotheses.

More recent work in RL has seen the development of other types of exploration

algorithms. For example, intrinsic motivation methods provide a bonus for

exploring interesting regions, such as those that have not been visited as much

previously or those which are surprising. While these seem in principle more

similar to children’s exploration, they are typically used more to expose

agents to a diverse set of experience during training, rather than to support

rapid learning and exploration at decision time.

Experimental setup

To alleviate some of the difficulties mentioned before in regards to applying

results from developmental psychology to AI research, we develop a setup in

which we have an exact comparison between children and agent behavior in the

exact same environment with exactly the same observations and maps. We do this

using DeepMind Lab, an existing platform for training and evaluating RL agents.

Moreover, we can restrict the action space in DeepMind Lab to four simple

actions (forward, backward, turn left, and turn right) using custom controllers

built in the lab, which make it easier for children to navigate around the

environment. Finally, in DeepMind lab we can procedurally generate a huge

amount of training data that we can use to bring agents up-to-speed on common

concepts like “wall” and “goal”.

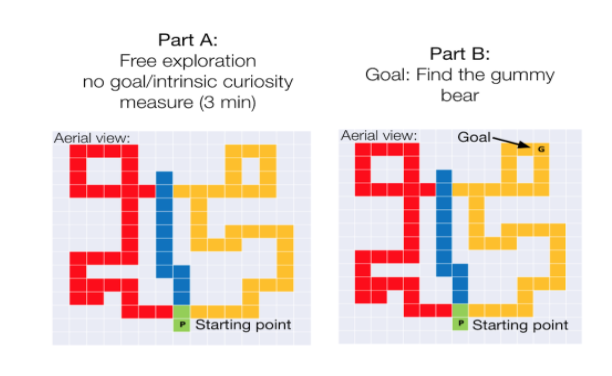

In the picture below you can see an overview of the parts of our experimental

setup. On the left, we see what it looks like when a child is exploring the

maze using the controller and the 4 possible actions they can take. In the

middle, we see what the child is seeing while navigating through the maze, and

on the right there is an aerial view of the child’s overall trajectory in the

maze.

Experimental results

We first investigated whether or not children (ages 4-5) that are naturally

more curious/exploratory in a maze are better able to succeed at finding a goal

later introduced at a random location. To test this, we have children explore

the maze for 3 minutes without any specific instructions or goals, and then

introduce a goal (represented as a gummy) in the same maze and then ask the

children to find the gummy. We measure both 1) the percentage of the maze

explored in the free exploration part of the task and 2) how long, in terms of

number of steps, it takes the children to find the gummy after it is

introduced.

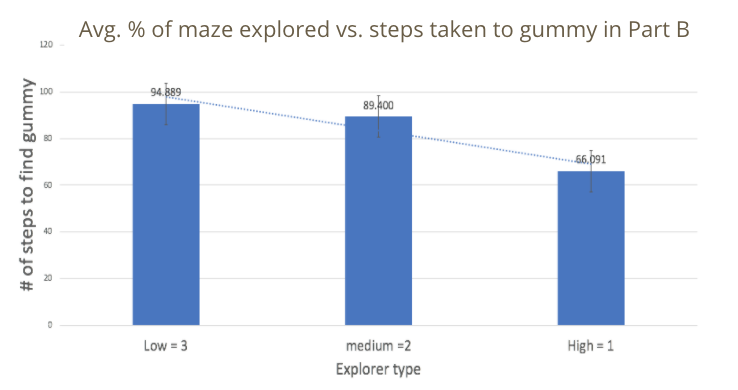

We breakdown the percentage of maze explored into 3 groups: low, medium and

high explorers. The low explorers explored around 22% of the maze on average,

the medium explorers explored around 44% of the maze on average, and the high

explorers explored around 71% of the maze on average. What we find is that the

less exploring the child did in the first part of the maze, the more steps it

took them to reach the gummy. This result can be visualized in the bar chart on

the left, where the Y-axis represents the number of steps it took them to find

the gummy, and the X-axis represents the explorer type. This data suggests a

trend that higher explorers are more efficient at finding a goal in this maze

setting.

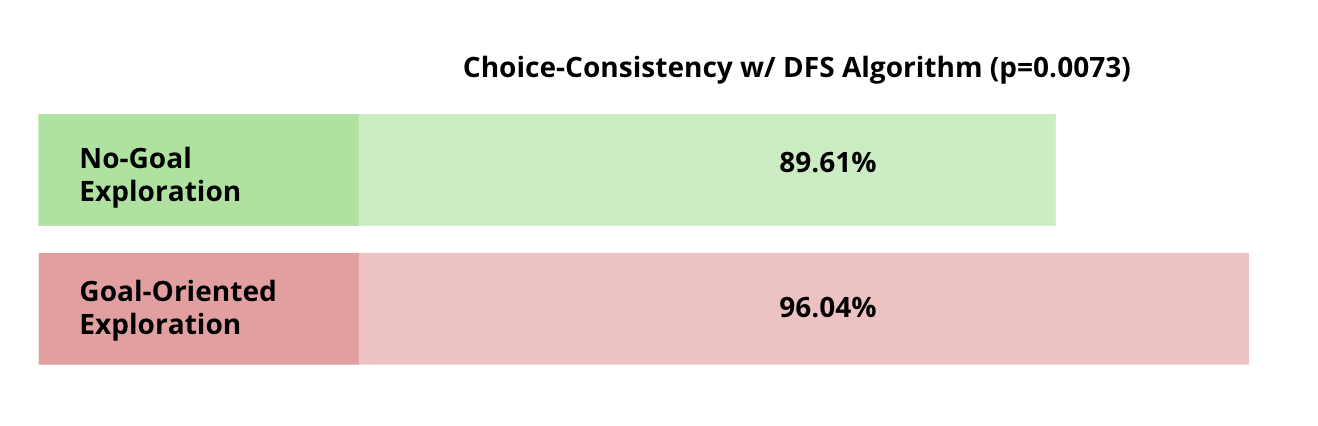

Now that we have data from the children in the mazes, How do we measure the

difference between an agent and a human trajectory? One method is to measure

if the child’s actions are “consistent” with that of a specific exploration

technique. Given a specific state or observation, a human or agent has a set of

actions that can be taken from this state. If the child takes the same action

that an agent would take, we call the action choice ‘consistent’. Otherwise the

action would not be consistent. We measure the percentage of states in a

child’s trajectory where the action taken by the child is consistent with an

algorithmic approach. We call this percentage “choice-consistency.”

One of the simplest algorithmic exploration techniques is to do a systematic

search method called depth-first search (DFS). From our task, recall that

children had a maze in which they first engaged in free exploration, and then a

goal-directed search. When we compare the consistency of the children’s

trajectories in those 2 settings with those of the DFS algorithm, we find that

kids in the free exploration setting take actions that are consistent with DFS

only 90% of the time, whereas in the goal oriented setting they match DFS 96%

of the time.

One way to interpret this result is that kids in the goal-oriented setting are

taking actions that are more systematic than in free exploration. In other

words, the children look more like a search algorithm when they are given a

goal.

Conclusion and future work

In conclusion, this work only begins to touch on a number of deep questions

regarding how children and agents explore. The experiments presented here just

begin to address questions regarding how much children and agents are willing

to explore; whether free versus goal-directed exploration strategies differ;

and how reward shaping affects exploration. Yet, our setup allows us to ask so

many more questions, and we have concrete plans to do so.

While DFS is a great first baseline for uninformed search, to enable a better

comparison, a next step is to compare the children’s trajectories to other

classical search algorithms and to that of RL agents from the literature.

Further, even the most sophisticated methods for exploration in RL tend to

explore only in the service of a specific goal, and are usually driven by error

rather than seeking information. Properly aligning the objectives of RL

algorithms with those of an exploratory child is an open question.

We believe that to truly build intelligent agents, they must do as children do:

actively explore their environments, perform experiments, and gather

information to weave together into a rich model of the world. In this

direction, we will be able to gain a deeper understanding of the way that

children and agents explore novel environments, and how to close the gap

between them.

This blog post is based on the following paper:

- Exploring Exploration: Comparing Children with RL Agents in Unified Environments.

Eliza Kosoy, Jasmine Collins, David M. Chan, Sandy Huang, Deepak Pathak, Pulkit Agrawal, John Canny, Alison Gopnik, and Jessica B. Hamrick

arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.02880 (2020)