Interaction with others is an important part of everyday life. No matter

the situation – whether it be playing a game of chess, carrying a

box together, or navigating lanes of traffic – we’re able to

seamlessly compete against, collaborate with, and acclimate to other

people.

Likewise, as robots become increasingly prevalent and capable, their

interaction with humans and other robots is inevitable. However, despite

the many advances in robot learning, most current algorithms are

designed for robots that act in isolation. These methods miss out on the

fact that other agents are also learning and changing – and so the

behavior the robot learns for the current interaction may not work

during the next one! Instead, can robots learn to seamlessly interact

with humans and other robots by taking their changing strategies into

account? In our new work (paper,

website), we

begin to investigate this question.

Actor-Critic (SAC) assumes that

the opponent (right) follows a fixed strategy, and only blocks on its

left side.

Interactions with humans are difficult for robots because humans and

other intelligent agents don’t have fixed behavior – their

strategies and habits change over time. In other words, they update

their actions in response to the robot and thus continually change the

robot’s learning environment. Consider the robot on the left (the agent)

learning to play air hockey against the non-stationary robot on the

right. Rather than hitting the same shot every time, the other robot

modifies its policy between interactions to exploit the agent’s

weaknesses. If the agent ignores how the other robot changes, then it

will fail to adapt accordingly and learn a poor policy.

The best defense for the agent is to block where it thinks the opponent

will next target. The robot therefore needs to anticipate how the

behavior of the other agent will change, and model how its own actions

affect the other’s behavior. People can deal with these scenarios on a

daily basis (e.g., driving, walking), and they do so without explicitly

modeling every low-level aspect of each other’s policy.

Humans tend to be bounded-rational (i.e., their rationality is limited

by knowledge and computational capacity), and so likely keep track of

much less complex entities during interaction. Inspired by how humans

solve these problems, we recognize that robots also do not need to

explicitly model every low-level action another agent will make.

Instead, we can capture the hidden, underlying intent – what we call

latent strategy (in the sense that it underlies the actions of the

agent) – of other agents through learned low-dimensional

representations. These representations are learned by optimizing neural

networks based on experience interacting with these other agents.

Learning and Influencing Latent Intent

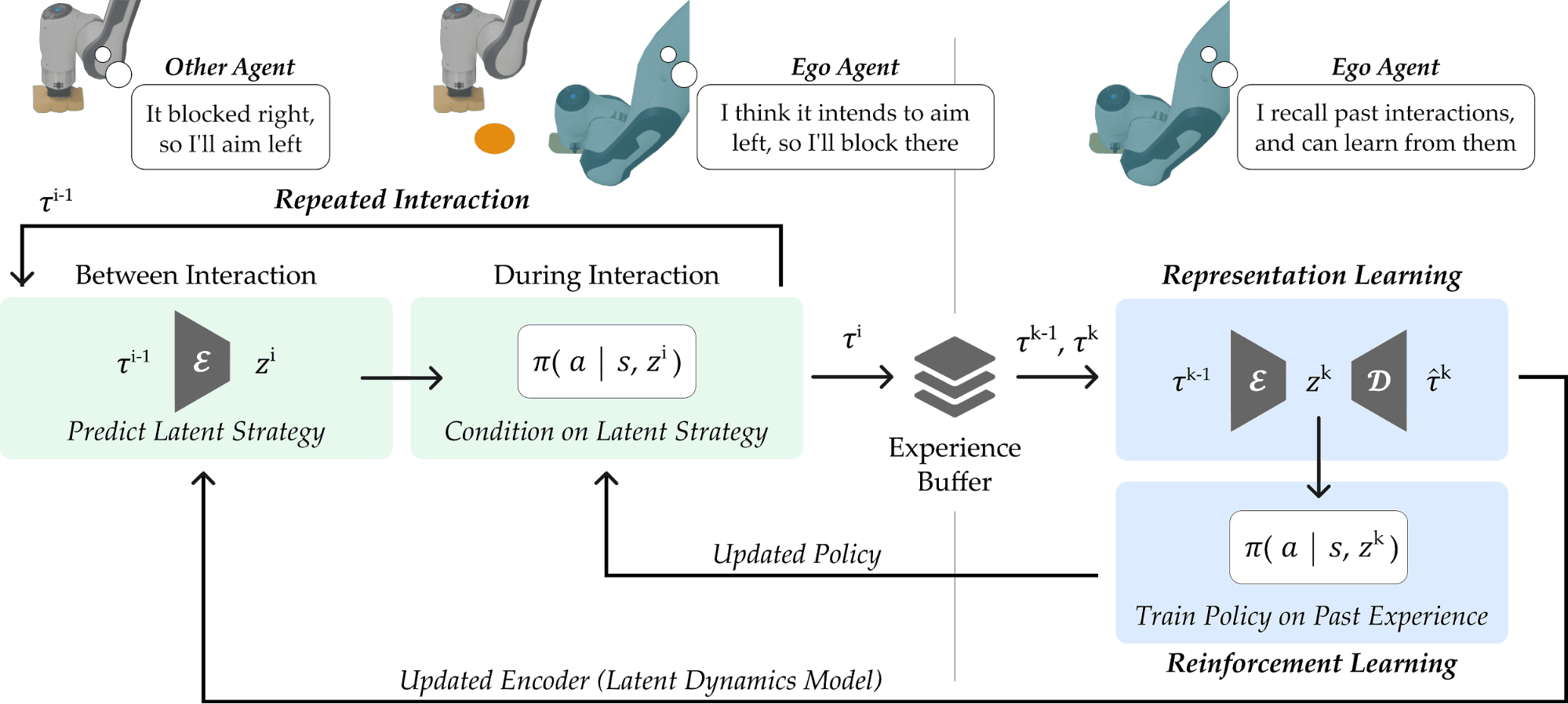

We propose a framework for learning latent representations of another

agent’s policy: Learning and Influencing Latent Intent (LILI). The

agent of our framework identifies the relationship between its behavior

and the other agent’s future strategy, and then leverages these latent

dynamics to influence the other agent, purposely guiding them towards

policies suitable for co-adaptation. At a high level, the robot learns

two things: a way to predict latent strategy, and a policy for

responding to that strategy. The robot learns these during interaction

by “thinking back” to prior experiences, and figuring out what

strategies and policies it should have used.

Modeling Agent Strategies

The first step, shown in the left side of the diagram above, is to learn

to represent the behavior of other agents. Many prior works assume

access to the underlying intentions or actions of other agents, which

can be a restrictive assumption. We instead recognize that a

low-dimensional representation of their behavior, i.e., their latent

strategy, can be inferred from the dynamics and rewards experienced by

the agent during the current interaction. Therefore, given a sequence of

interactions, we can train an

encoder-decoder

model; the encoder embeds interaction and predicts the next

latent strategy , and the decoder takes this prediction

and reconstructs the transitions and rewards observed during interaction

.

Influencing by Optimizing for Long-Term Rewards

Given a prediction of what strategy the other agent will follow next,

the agent can learn how to react to it, as illustrated on the right

side of the diagram above. Specifically, we train an agent policy

with reinforcement learning (RL) to

make decisions conditioned on the latent strategy predicted

by the encoder.

However, beyond simply reacting to the predicted latent strategy, an

intelligent agent should proactively influence this strategy to

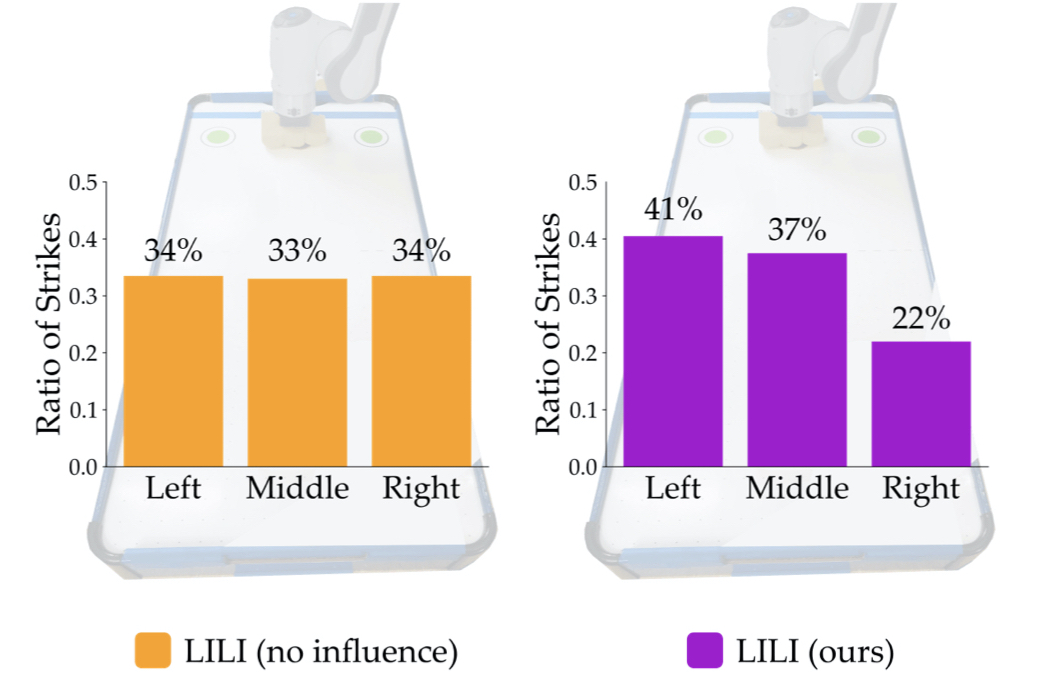

maximize rewards over repeated interactions. Returning to our hockey

example, consider an opponent with three different strategies: it fires

to the left, down the middle, or to the right. Moreover, left-side shots

are easier for the agent to block and so gives a higher reward when

successfully blocked. The agent should influence its opponent to adopt

the left strategy more frequently in order to earn higher long-term

rewards.

For learning this influential behavior, we train the agent policy

to maximize rewards across multiple interactions:

With this objective, the agent learns to generate interactions that

influence the other agent, and hence the system, toward outcomes that

are more desirable for the agent or for the team as a whole.

Experiments

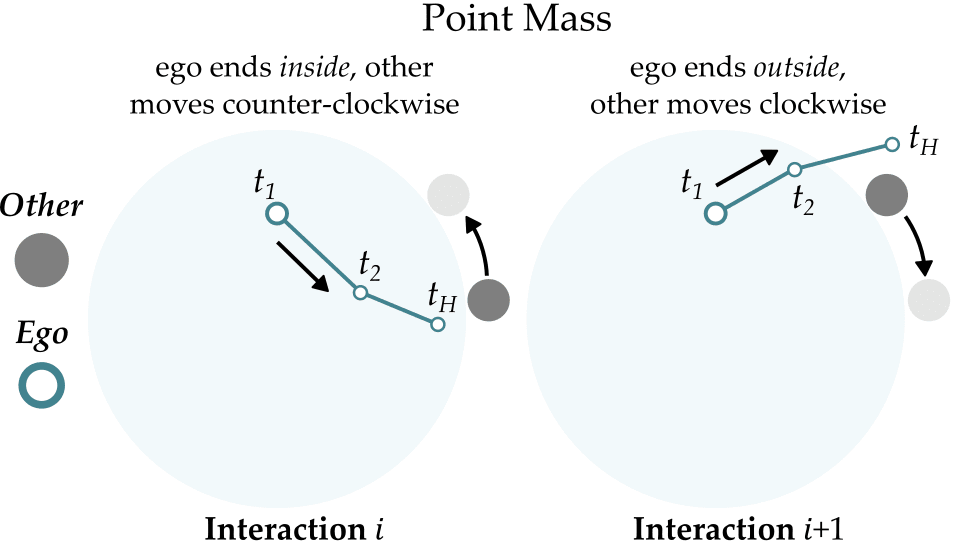

2D Navigation

We first consider a simple point mass navigation task. Similar to

pursuit-evasion games, the agent needs to reach the other agent (i.e.,

the target) in a 2D plane. This target moves one step clockwise or

counterclockwise around a circle depending on where the agent ended the

previous interaction. Because the agent starts off-center, some target

locations can be reached more efficiently than others. Importantly, the

agent never observes the location of the target.

Below, we visualize 25 consecutive interactions from policies learned by

Soft Actor-Critic (SAC) (a standard RL algorithm), LILI (no influence),

and LILI. LILI (no influence) corresponds to our approach without the

influencing objective; i.e., the agent optimizes rewards accumulated in

a single interaction. The gray circle represents the target, while the

teal line marks the trajectory taken by the agent and the teal circle

marks the agent’s position at the final timestep of the interaction.

The SAC policy, at convergence, moves to the center of the circle in

every interaction. Without knowledge of or any mechanism to infer where

the other agent is, the center of the circle gives the highest stable

rewards. In contrast, LILI (no influence) successfully models the other

agent’s behavior dynamics and correctly navigates to the other agent,

but isn’t trained to influence the other agent. Our full approach LILI

does learn to influence: it traps the other agent at the top of the

circle, where the other agent is closest to the agent’s starting

position and yields the highest rewards.

Robotic Air Hockey

Next, we evaluate our approach on the air hockey task, played between

two robotic agents. The agent first learns alongside a robot opponent,

then plays against a human opponent. The opponent is a rule-based agent

which always aims away from where the agent last blocked. When blocking,

the robot does not know where the opponent is aiming, and only observes

the vertical position of the puck. We additionally give the robot a

bonus reward if it blocks a shot on the left of the board, which

incentivizes the agent to influence the opponent into aiming left.

In contrast to the SAC agent, the LILI agent learns to anticipate

the opponent’s future strategies and successfully block the different

incoming shots.

Because the agent receives a bonus reward for blocking left, it should

lead the opponent into firing left more often. LILI (no influence) fails

to guide the opponent into taking advantage of this bonus: the

distribution over the opponent’s strategies is uniform. In contrast,

LILI leads the opponent to strike left 41% of the time, demonstrating

the agent’s ability to influence the opponent. Specifically, the agent

manipulates the opponent into alternating between the left and middle

strategies.

Finally, we test the policy learned by LILI (no influence) against a

human player following the same strategy pattern as the robot opponent.

Importantly, the human has imperfect aim and so introduces new noise to

the environment. We originally intended to test our approach LILI with

human opponents, but we found that – although LILI worked well when

playing against another robot – the learned policy was too brittle

and did not generalize to playing alongside human opponents. However,

the policy learned with LILI (no influence) was able to block 73% of

shots from the human.

Final Thoughts

We proposed a framework for multi-agent interaction that represents the

behavior of other agents with learned high-level strategies, and

incorporates these strategies into an RL algorithm. Robots with our

approach were able to anticipate how their behavior would affect another

agent’s latent strategy, and actively influenced that agent for more

seamless co-adaptation.

Our work represents a step towards building robots that act alongside

humans and other agents. To this end, we’re excited about these next

steps:

-

The agents we examined in our experiments had a small number of simple strategies determining their behavior. We’d like to study the scalability of our approach to more complex agent strategies that we’re likely to see in humans and intelligent agents.

-

Instead of training alongside artificial agents, we hope to study the human-in-the-loop setting in order to adapt to the dynamic needs and preferences of real people.

This post is based on the following paper:

Annie Xie, Dylan P. Losey, Ryan Tolsma, Chelsea Finn, Dorsa Sadigh.

Learning Latent Representations for Multi-Agent Interaction.

Project webpage

Finally, thanks to Dylan Losey, Chelsea Finn, Dorsa Sadigh, Andrey Kurenkov, and Michelle Lee for valuable feedback on this post.