Current machine learning methods provide unprecedented accuracy across a range

of domains, from computer vision to natural language processing. However, in

many important high-stakes applications, such as medical diagnosis or

autonomous driving, rare mistakes can be extremely costly, and thus effective

deployment of learned models requires not only high accuracy, but also a way to

measure the certainty in a model’s predictions. Reliable uncertainty

quantification is especially important when faced with out-of-distribution

inputs, as model accuracy tends to degrade heavily on inputs that differ

significantly from those seen during training. In this blog post, we will

discuss how we can get reliable uncertainty estimation with a strategy that

does not simply rely on a learned model to extrapolate to out-of-distribution

inputs, but instead asks: “given my training data, which labels would make

sense for this input?”.

To illustrate how this can allow for more reasonable predictions on

out-of-distribution data, consider the following example where we attempt to

classify automobiles, where all the class 1 training examples are sedans and

class 2 examples are large buses.

Figure 1: Given previously seen examples, it is uncertain what the label for

the new query point should be. Different classifiers that work well on the

training set can give different predictions on the query point.

A classifier could potentially fit the training labels correctly based on

several different explanations; for example, it could notice that buses are all

longer than sedans and classify accordingly, or it could perhaps pay attention

to the height of the vehicle instead. However, if we try to simply extrapolate

to an out-of-distribution image of a limousine, the classifier’s output could

be unpredictable and arbitrary. A classifier based on length could note that

the limousine is similar to the buses in its length and confidently predict

class 2, while a classifier utilizing the height could confidently predict

class 1. Based only on the training set, there is not enough information to

accurately decide which class a limousine should fit into, so we would ideally

want our classifier to indicate uncertainty instead of providing arbitrary

confident predictions for either class. On the other hand, if we explicitly try

to find models that explain each potential label, we would find reasonable

explanations for either label, suggesting that we should be uncertain about

predicting which class the limousine belongs to.

We can instantiate this reasoning with an algorithm that, for every possible

label, explicitly updates the model to try to explain that label for the query

point and combines the different models to obtain well-calibrated predictions

for out-of-distribution inputs. In this blog post, we will motivate and

introduce

amortized conditional normalized maximum likelihood

(ACNML), a practical instantiation of this idea that enables reliable

uncertainty estimation with deep neural networks.

Conditional Normalized Maximum Likelihood

Our method extends a prediction strategy from the minimum description length

(MDL) literature known as conditional normalized maximum likelihood (CNML),1

which has been studied for its theoretical properties, but is computationally

intractable for all but the simplest problems. We will first review CNML and

discuss how its predictions can lead to conservative uncertainty estimates. We

will then describe our method, which allows for a practical application of CNML

to obtain uncertainty estimates for deep neural networks.

The CNML distribution is derived from achieving a notion of minimax optimality,

where we define a notion of regret for each label and choose the distribution

that minimizes the worst case regret over labels. Given a training set

$D_{rm train}$, a query input $x$, and a set of potential models $Theta$, we

define the regret for each label to be the difference between the negative

log-likelihood loss for our distribution and the loss under the model that best

fits the training dataset together with the query point and label.

Intuitively, minimizing the worst case regret over labels then ensures our

predictive distribution is conservative, as it cannot assign low probabilities

to any labels that appear consistent with our training data, where consistency

is determined by the model class.

The minimax optimal distribution given a particular input $x$ and training set

$mathcal D$ can be explicitly computed as follows:

-

For each label $y$, we append $(x,y)$ to our training set and compute the

new optimal parameters $hat theta_y$ for this modified training set. -

Use $hat theta_y$ to assign probability for that label.

-

Since these probabilities will now sum to a number greater than 1, we

normalize to obtain a valid distribution over labels.

<!–

Daniel: no need for the image, equation above works fine.

–>

CNML has the interesting property that it explicitly optimizes the model to

make predictions on the query input, which can lead to more reasonable

predictions than simply extrapolating using a model obtained only from the

training set. It can also lead to more conservative predictions on

out-of-distribution inputs, since it would be easier to fit different labels

for out-of-distribution points without affecting performance on the training

set.

We illustrate CNML with a 2-dimensional logistic regression example. We compare

heatmaps of CNML probabilities with the maximum likelihood classifier to

illustrate how CNML provides conservative uncertainty estimates on points away

from the data. With this model class, CNML expresses uncertainty and assigns a

uniform distribution to any query point where the dataset remains linearly

separable (meaning there exists a linear decision boundary could correctly

classify all data points) regardless of which label was assigned for the query

point.

Figure 2: Here, we show the heatmap of CNML predictions (left) and the

predictions of the training set MLE $hat theta_{text{train}}$ (right). The

training inputs are shown with blue (class 0) and orange (class 1) dots. Blue

shading indicates that higher probability for class 0 on that input and red

shading indicates higher probability to class 1, with darker colors indicating

more confident predictions. We note that while the original classifier assigns

confident predictions for most inputs, CNML assigns close to uniform for most

points between the two clusters of training points, indicating high uncertainty

about these ambiguous inputs.

We illustrate how CNML computes these probabilities by illustrating the base

classifier predictions under parameters $hat theta_{text{train}}$ (the

training set MLE), as well as $hat theta_{text{0}}$, $hat

theta_{text{1}}$, the parameters computed by CNML after assigning the

labels 0 and 1 respectively to a query point.

We first consider an out-of-distribution query point far away from any of the

training inputs (shown in pink in the bottom of the leftmost image). In the

left image, we see the original decision boundary for $hat

theta_{text{train}}$ confidently classifies the query point as class 0. In

the middle, we see the decision boundary of $hat theta_0$ similarly

classifies the query point as class 0. However, we see in the rightmost image

that $hat theta_1$ is able to confidently classify the query point as class 1.

Since $hat theta_0$ confidently predicts class 0 for the query point and

$hat theta_1$ confidently predicts class 1, CNML normalizes the two

predictions to assign roughly equal probability to either label.

Figure 3: Query point shown in pink. Both $hat theta_{text{train}}$ and

$hat theta_0$ classify the query point as class 0, but $hat theta_1$ is

able to classify it as class 1.

On the other hand, for an in-distribution query point (again shown in pink) in

the middle of the class 0 training inputs, no linear classifier can fit a label

of 1 to the query point while still accurately fitting the rest of the training

data, so the CNML distribution still confidently predicts class 0 on this query

point.

Figure 4: Query point shown in pink. All parameters are forced to classify the

query point as class 0 since it is in the middle of the class 0 training

points.

Controlling Conservativeness via Regularization

We see in Figure 2 that CNML probabilities are uniform on most of the input

space, arguably being too conservative. In this case, the model class is in

some sense too expressive, as linear predictors with large coefficients that

can assign arbitrarily high probabilities to each label as long as the data

remains linearly separable. This problem is exacerbated with even more

expressive model classes like deep neural networks, which can potentially fit

arbitrary labels. In order to have CNML give more useful predictions, we would

need to constrain the allowed set of models to better reflect our notion of

reasonable models.

To accomplish this, we generalize CNML to incorporate regularization via a

prior term, resulting in conditional

normalized maximum a posteriori

(CNMAP) instead. Instead of computing maximum likelihood

parameters for the training dataset and the new input and label, we compute

maximum a posteriori (MAP) solutions instead, with the prior term $p(theta)$

serving as a regularizer to limit the complexity of the selected model.

<!–

Daniel Seita: above equation in LaTeX is fine.

–>

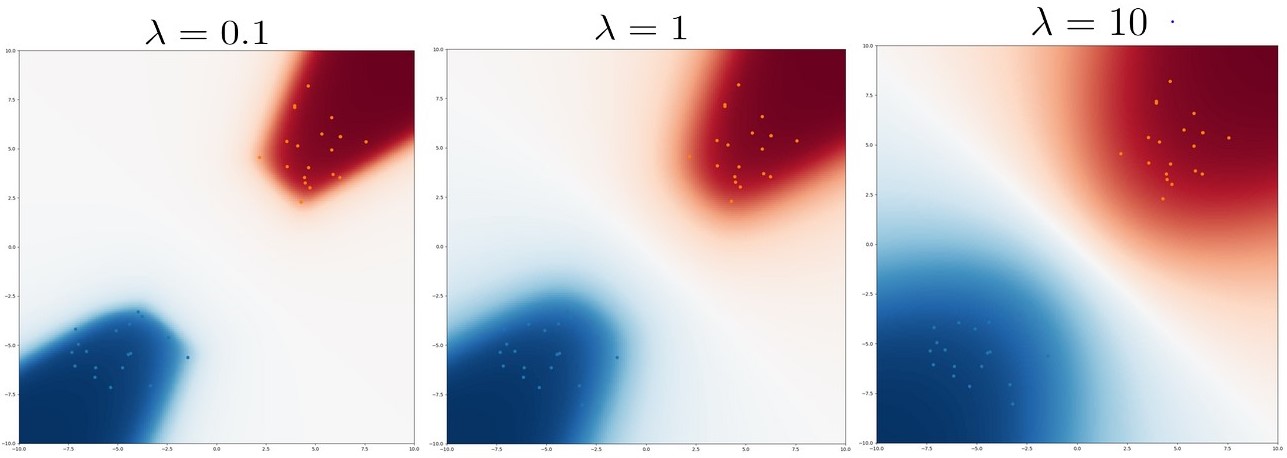

Going back to the logistic regression example, we add different levels of L2

regularization to the parameters (corresponding to Gaussian priors) and plot

CNMAP probabilities in Figure 3 below. As regularization increases, CNML

becomes less conservative, with the assigned probabilities transitioning much

more smoothly as one moves away from the training points.

Figure 5: Heatmaps of CNMAP probabilities under varying amounts of

regularization $lambda |w|_2^2$. Increasing regularization leads to less

conservative predictions.

Computational Intractability

While we see that CNML is able to provide conservative predictions for OOD

inputs, computing CNML predictions requires retraining the model using the

entire training set multiple times for each test input, which can be very

computationally expensive. While explicitly computing CNML distributions was

feasible in our logistic regression example with small datasets, it would be

computationally intractable to compute CNML naively with datasets consisting of

thousands of images and using deep convolutional neural networks, as retraining

the model just once could already take many hours. Even initializing from the

solution to the training set and finetuning for several epochs after adding the

query input and label could still take several minutes per input, rendering it

impractical to use with deep neural networks and large datasets.

Amortized Conditional Normalized Maximum Likelihood

Since exactly computing CNML or CNMAP distributions is computationally

infeasible in deep learning settings due to the need to optimize over large

datasets for each new input and label, we need a tractable approximation. In

our method, amortized conditional normalized maximum likelihood (ACNML), we

utilize approximate Bayesian posteriors to capture necessary information about

the training data in order to efficiently compute the MAP/MLE solutions for

each datapoint. ACNML amortizes the costs of repeatedly optimizing over the

training set by first computing an approximate Bayesian posterior, which serves

as a compact approximation to the training losses.

CNMAP and Bayesian Posteriors

We note that the main computational bottleneck is the need to optimize over the

entire training set for each query point. In order to sidestep this issue, we

first show a relationship between the MAP parameters needed in CNMAP and

Bayesian posterior densities:

<!–

$$hat theta_y = arg max_theta log p_{theta}(y vert x) + log p_{theta}(D_{text{train}}) + log p(theta)$$

Daniel Seita: above equation in LaTeX is fine.

–>

Rather than computing optimal parameters for the new query point and the

training set, we can reformulate CNMAP as optimizing over just the query point

and a posterior density. With a uniform prior (equivalent to having no

regularizer), we can recover the maximum likelihood parameters to perform CNML

if desired.2

ACNML now utilizes approximate Bayesian inference to replace the exact Bayesian

posterior density with a tractable density $q(theta)$. As many methods have

been proposed for approximate Bayesian inference in deep learning, we can

simply utilize any approximate posterior that provides tractable densities for

ACNML, though we focus on Gaussian approximate posteriors for simplicity and

computational efficiency. After computing the approximate posterior once during

training, the test-time optimization procedure becomes much simpler, as we only

need to optimize over our approximate posterior instead of the training set.

When we instantiate ACNML and initialize from the MAP solution, we find that it

typically takes only a handful of gradient updates to compute new (approximate)

optimal parameters for each label, resulting in much faster test-time inference

than a naive CNML instantiation that fine tunes using the whole training set.

In our paper, we analyze the

approximation error incurred by using a particular Gaussian posterior in place

of the exact training data likelihoods, and show that under certain

assumptions, the approximation is accurate when the training set is large.

Experiments

We instantiate ACNML with two different Gaussian posterior approximations,

SWAG-Diagonal and

KFAC-Laplace

and train models on the CIFAR-10 image classification dataset. To evaluate

out-of-distribution performance, we then evaluate on the CIFAR-10 Corrupted

datasets, which apply a diverse range of common image corruptions at different

intensities, allowing us to see how well methods perform under varying levels

of distribution shift. We compare against methods using Bayesian

marginalization, which average predictions across different models sampled from

the approximate posterior. We note that all methods provide very similar

accuracy both in-distribution and out-of-distribution, so we focus on comparing

uncertainty estimates.

Figure 7: Reliability Diagrams comparing ACNML against the corresponding

Bayesian model averaging method (SWAGD) and the MAP solution (SWA). ACNML

generally predicts with lower confidence than other methods, leading to

comparatively better uncertainty estimation as the data becomes more

out-of-distribution.

We first examine ACNML’s predictions using reliability diagrams, which

aggregate the test data points into buckets based on how confident the model’s

predictions are, then plot the average confidence in a bucket against the

actual accuracy of the predictions. These diagrams show the distribution of

predicted confidences and can capture how effectively a model’s confidence

reflects the actual uncertainty over the prediction.

As we would expect from our earlier discussion about CNML, we find that ACNML

reliably gives more conservative (less confident) predictions than other

methods, to the point where its predictions are actually underconfident on

the in-distribution CIFAR10 test set where all methods provide very accurate

predictions. However, on the out-of-distribution CIFAR10-C tasks where

classifier accuracy degrades, ACNML’s conservativeness provides much more

reliable confidence estimates, while other methods tend to be severely

overconfident.

Figure 8: ECE comparisons: We compare instantiations of ACNML with two

different approximate posteriors against their Bayesian counterparts.

We quantitatively measure calibration using the

Expected Calibration Error,

which uses the same buckets as the reliability diagrams and

computes the average calibration error (absolute difference between average

confidence and accuracy within the bucket) over all buckets. We see that ACNML

instantiations provide much better calibration than their Bayesian counterparts

and the deterministic baseline as the corruption intensities increase and the

data becomes more out-of-distribution.

Discussion

In this post, we discussed how we can obtain reliable uncertainty estimates on

out-of-distribution data by explicitly optimizing on the data we wish to make

predictions on instead of relying on trained models to extrapolate from the

training data. We then showed that this can be done concretely with the CNML

prediction strategy, a scheme that has been studied theoretically but is

computationally intractable to apply in practice. Finally we presented our

method, ACNML, a practical approximation to CNML that enables reliable

uncertainty estimation with deep neural networks. We hope that this line of

work will help enable broader applicability of large scale machine learning

systems, especially in safety-critical domains where uncertainty estimation is

a necessity.

We thank Sergey Levine and Dibya Ghosh for providing valuable feedback on this post.

This post is based on this following paper:

- Aurick Zhou, Sergey Levine.

Amortized Conditional Normalized Maximum Likelihood.

-

For additional background on MDL and CNML, we refer to the following

textbook.

The particular variant of CNML used here is referred to as CNML-3 in the text, and as sNML-1 in

Roos et al. ↩ -

Despite referring to maximum likelihood in the name, ACNML actually

approximates the CNMAP procedure, with CNML being a special case of CNMAP

by using a uniform prior as regularizer. In practice, due to the

over-conservativeness of CNML mentioned before, we will use non-uniform

priors (as used by the Bayesian deep learning methods we build off of). ↩