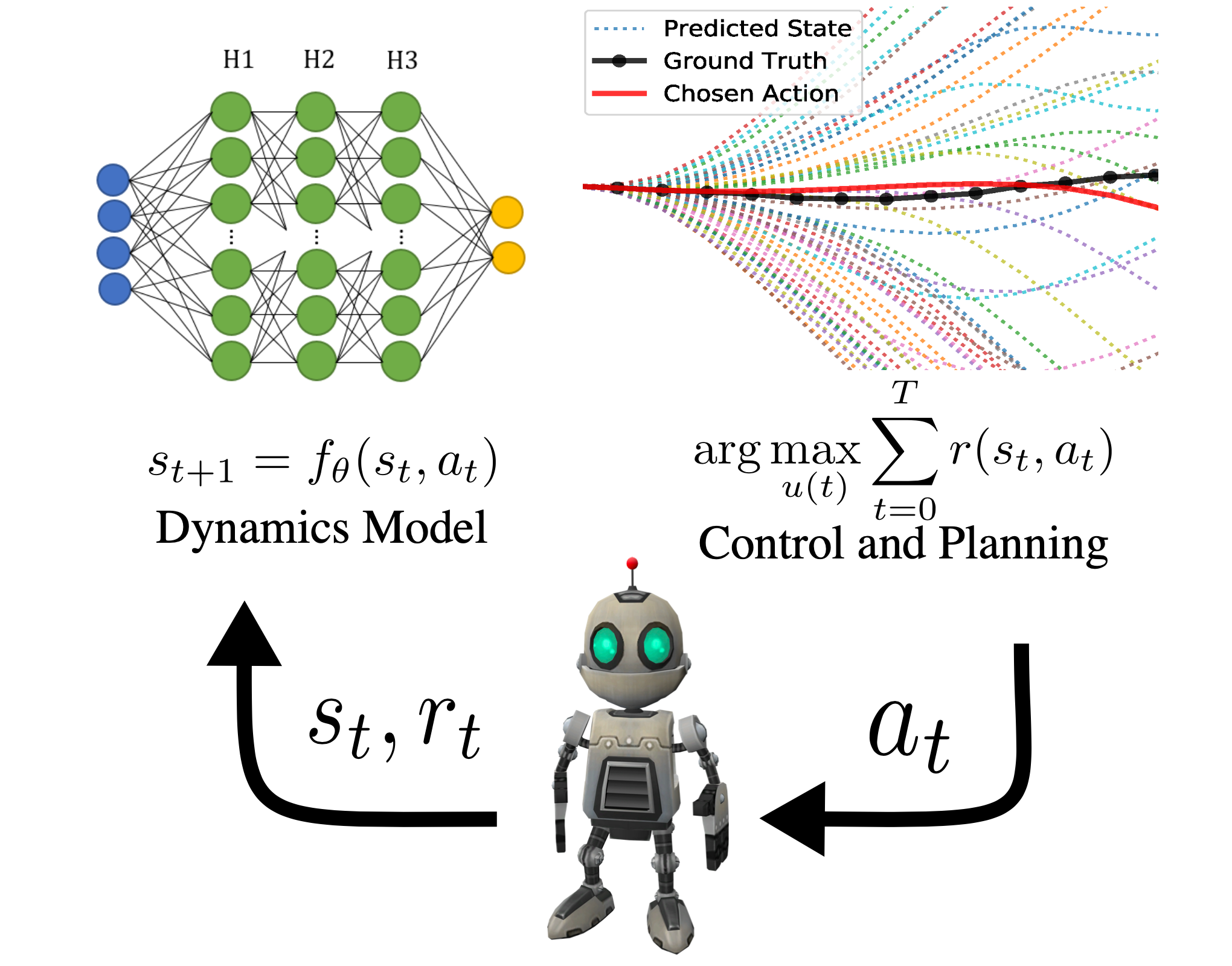

Model-based reinforcement learning (MBRL) is a variant of the iterative

learning framework, reinforcement learning, that includes a structured

component of the system that is solely optimized to model the environment

dynamics. Learning a model is broadly motivated from biology, optimal control,

and more – it is grounded in natural human intuition of planning before acting. This intuitive

grounding, however, results in a more complicated learning process. In this

post, we discuss how model-based reinforcement learning is more susceptible to

parameter tuning and how AutoML can help in finding very well performing

parameter settings and schedules. Below, left is the expected behavior of an

agent maximizing velocity on a “Half Cheetah” robotic task, and to the right is

what our paper with hyperparameter tuning finds.

MBRL

Model-based reinforcement learning (MBRL) is an iterative framework for solving

tasks in a partially understood environment. There is an agent that repeatedly

tries to solve a problem, accumulating state and action data. With that data,

the agent creates a structured learning tool – a dynamics model – to reason

about the world. With the dynamics model, the agent decides how to act by

predicting into the future. With those actions, the agent collects more data,

improves said model, and hopefully improves future actions.

AutoML

Humans are pretty poor at internalizing higher-dimensional relationships.

Unfortunately, all ML systems come with hyperparameters that have complex

higher-dimensional relationships. Manually searching for configurations or

schedules that work well is a tedious and unrewarding task, so let’s let a

computer do it for us. Automated Machine Learning (AutoML) is a field

dedicated to the study of using machine learning algorithms to tune our machine

learning tools. However, there have not been many attempts in using AutoML

methods for RL so far, (for more on AutoRL see this blog post) even

though, given the success of AutoML in Supervised Learning, one could expect a

bigger impact in higher-dimensional RL. This is partly due to the harder

problem of dynamic hyperparameter tuning (where hyperparameters can change

within a run), but more on that later.

Why MBRL is challenging to tune

Why may we see even more impact of AutoML on MBRL when compared to model-freel RL?

First off, more machine learning parts equals a harder problem,

so there is a greater potential to make hyperparameter tuning way more

impactful to MBRL. Normally, a graduate student fine tunes one problem at a

time with a handful of variables, but in MBRL there are two weirdly intertwined

systems: the model and the planner (the objectives are mismatched). So, no human is likely to be able

to find the perfect parameters. Much research progress, still, is yielding to

luck when it comes to finding the right hyperparameters. Even though it is an

open problem to see if computers can find the true optimum, as mentioned

before, computers are much better at optimizing in high-dimensional spaces such

as RL.

Secondly, the benchmark where most RL algorithms are tested in recent work –

a simulator called Mujoco – has been used for years and performance of

the best algorithms is close to maxing out the realistic behaviors in the

simulator. Such a realistic solution for Half Cheetah can be seen in the video

on the left at the beginning of the post.

Mujoco showed up as a favorite of Deep RL because it was available when a

massive growth phase was coming through. It is a decent simulator, relatively

lightweight, and easy-enough to use (though, Mujoco is expensive, has fairly

strict licensing, and not a completely accurate portrayal of the real world).

Mujoco has worked for individual researchers and teams growing into a new area,

but not necessarily great for the long-term health of the field. Researchers

have tracked the so-called state-of-the-art (SOTA) performance of algorithms

across the group of tasks available on the benchmark. This has led to relying

on this benchmark as a surrogate objective for what humans truly want to

optimize – performance in the real world – and left progress in the research

field vulnerable to being gamed. And in such problems, where optimal

solutions may be unintuitive, computers are even more likely to substantially

outperform humans.

Static vs. Dynamic Parameter Tuning

Reinforcement learning, or any iterative framework for that matter, poses an

interesting challenge for AutoML and parameter tuning research: the best

parameters might change over time. The ideal parameters shift because the

data used to train any model changes over time. This is different from a more

classical approach to AutoML – on a Supervised Learning task, static

parameter configurations are much more likely to perform well (such as the

weights and biases of a deployed vision model).

When the distribution of the data we are using changes over time, we look to

dynamic hyperparameter tuning where the hyperparameters of the model or

optimizer are adapted over time. In the case of MBRL, this can have an elegant

interpretation: as the agent gets more data, it can train a more accurate

model, and then it may want to use that model to plan further into the future.

This would translate to a dynamic tuning of the model predictive horizon

hyperparameter variable used in the action optimization. Static hyperparameters –

which most RL algorithms report in tables in the appendix of their papers –

are likely not going to be able to deal with shifting distributions. The

algorithm used to demonstrate this is Hyperband (more later in the post). It is

a static tuning method and the chosen parameters show a low correlation with

reward across a longer run or to another task. For more details on the

specifics of static tuning, see the paper, but the crucial question is: how

much can an RL agent gain with dynamics tuning. Normally, this gain is measured

on the performance of an algorithm on one task.

This finding, however, does not mean that static tuning does not have its uses.

In this paper, we further studied what aspects of static and dynamic are most

important for a practitioner depending on what they want to achieve –

transferability (across runs on the same task or across tasks) or final

performance. We showed that static parameter configurations learn

hyperparameter settings that are more robust to transferring. By design,

dynamic configurations make many more choices about the parameter settings than

static configurations, thus making it very challenging to tune dynamic

configurations by hand and without automatic HPO methods. With an increasing

number of decision points, it becomes more and more likely that each choice we

make is specifically tailored to the environment and even the current run at

hand.

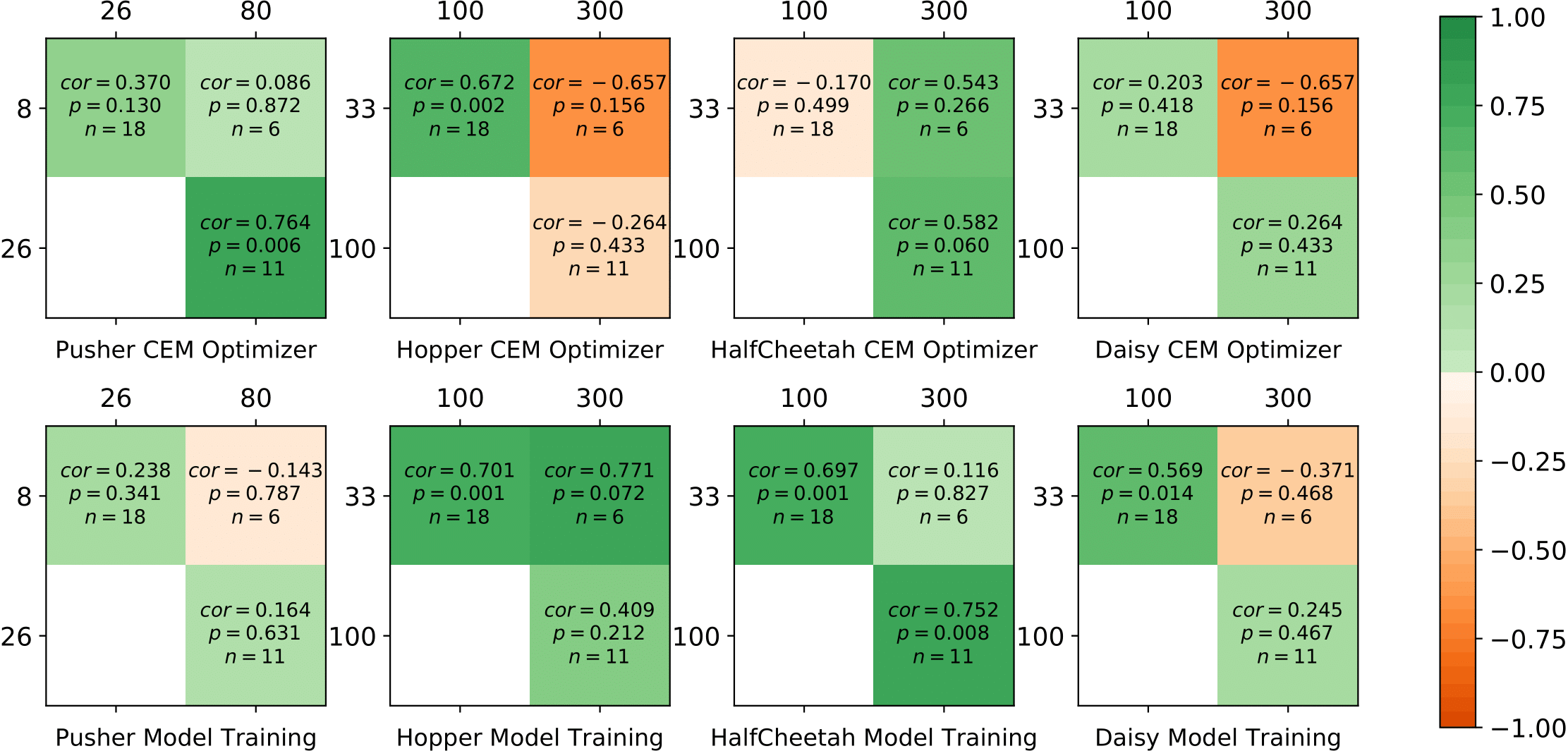

Weak or even negative correlation across different budgets are found in most of

the environments with static and transferred tunings, which shows different

configurations perform best for different training durations and that dynamic

tuning may be needed. Above shows the Spearman rank correlation of

hyperparameters sampled by Hyperband across trials when training. $cor$ is the

correlation coefficient, $p$ is the p-value for the hypothesis test and $n$ gives

the number of configurations trained in both fidelities.

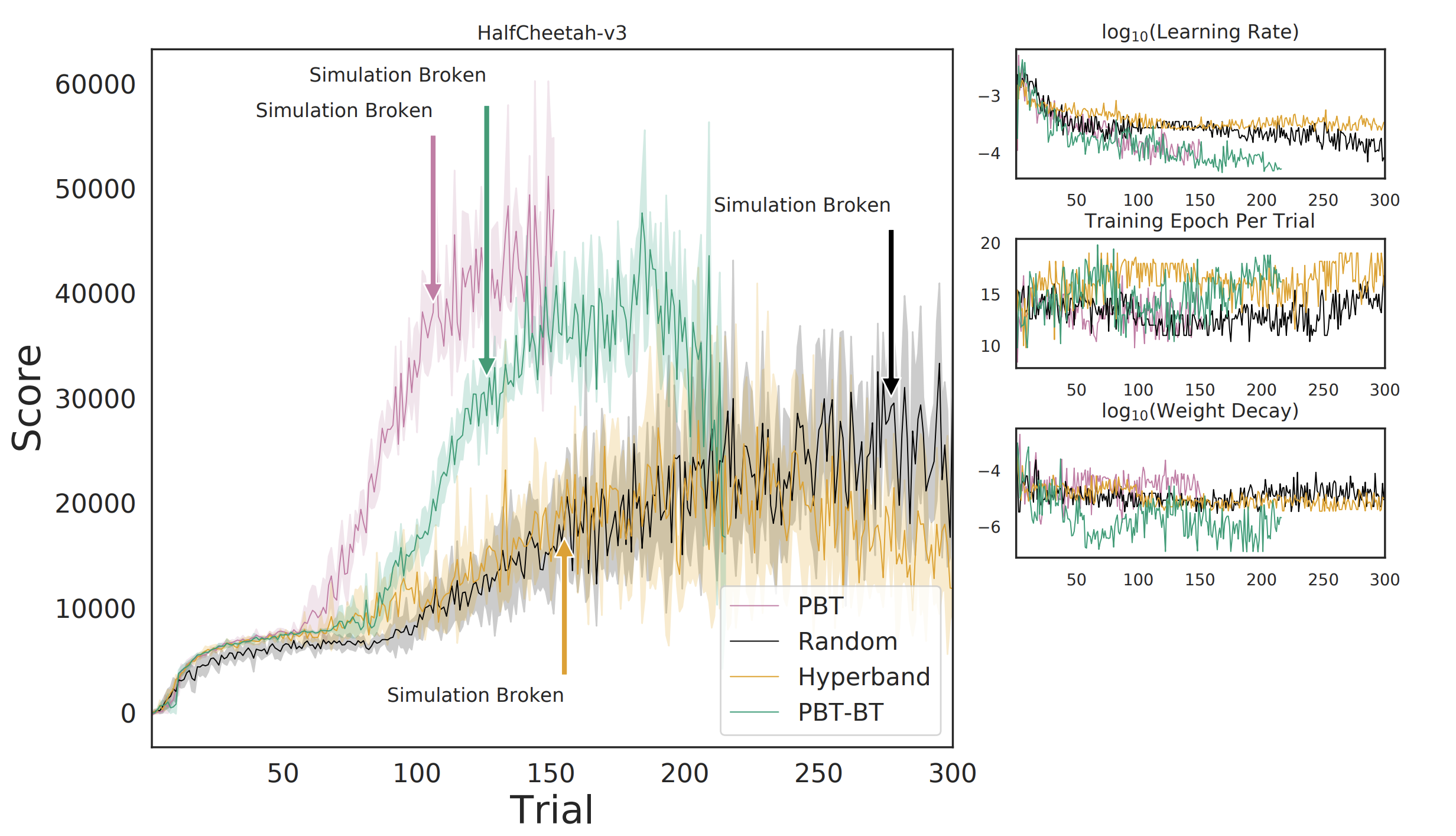

Breaking the simulator

Combining AutoML with MBRL dramatically beats the SOTA results on a couple of

Mujoco tasks by using existing MBRL algorithms with both dynamic and static

parameter tuning. With sufficient hyperparameter tuning, the MBRL algorithm

(PETS) literally breaks Mujoco. The Mujoco log reads something akin to:

WARNING: Nan, Inf or huge value in QACC at DOF 0. The simulation is unstable. Time = 40.4200.

This correlates to the task being solved in a non-intuitive, exploitative

manner: the Half Cheetah cartwheels.

Normally, the Half Cheetah is supposed to run. However, through hyperparameter

tuning, the agent can experience that stumbling and flipping over can be

converted into a successful cartwheel. Chaining such cartwheels back to back

allows it to build up much more speed than otherwise possible. So much, in

fact, that the simulator can’t keep up and breaks. This shows that we have not

yet explored the full potential of existing agent implementations and that

AutoML can be a key component in doing so. The paper has a much, much wider

range of results on multiple environments, but I leave that to the reader. The

paper has interesting tradeoffs between optimizing the model (learning the

dynamics) and the controller (solving the reward-maximization problem).

Additionally, it shows how dynamically changing the parameters throughout a

trial can be useful, such as increasing your model horizon as the algorithm

collects data and the model becomes more accurate. We analyse in-depth the

impact of design decisions on the following tuning methods:

- Population Based Training (PBT): An evolutionary approach to hyperparameter tuning, where the best performing members are modified and replace worse performing configurations (link).

- Population Based Training with Backtracking (PBT-BT): Population-based training where the agents can return to past configurations during the learning process.

- Hyperband: A Bandit-Based Approach to Hyperparameter Optimization (link).

- Random Search: A method where configurations are generated within the hyperparameter search space (example).

Conclusion

Ultimately, this is a paper that can really move the field forward by showing

the ceiling is much higher than expected for current deep RL algorithms and

that new benchmarking tasks are needed to facilitate continued development of

the research area. Knowing that the last generation of MBRL algorithms still

has substantial performance to be cultivated motivates more interesting

numerical research revisiting past methods as the future is designed.

As the Mujoco simulator seems to be reaching its maximum in terms of logged

performance, it is time for a new generation of simulators and tasks to

benchmark developments in deep reinforcement learning. In creating new tasks,

there is an exciting opportunity to move our research methods closer to real

world applications — providing a harder challenge with a growing potential

payoff.

This post is based on the following paper:

- On the Importance of Hyperparameter Optimization for Model-based Reinforcement Learning

Baohe Zhang, Raghu Rajan, Luis Pineda, Nathan Lambert, André Biedenkapp, Kurtland Chua, Frank Hutter, Roberto Calandra

Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (AISTATS), 2021.

A video explaining the paper