2D block quantization for Float8 (FP8) holds the promise of improving the accuracy of Float8 quantization while also accelerating GEMM’s for both inference and training. In this blog, we showcase advances using Triton for the two main phases involved in doing block quantized Float8 GEMMs.

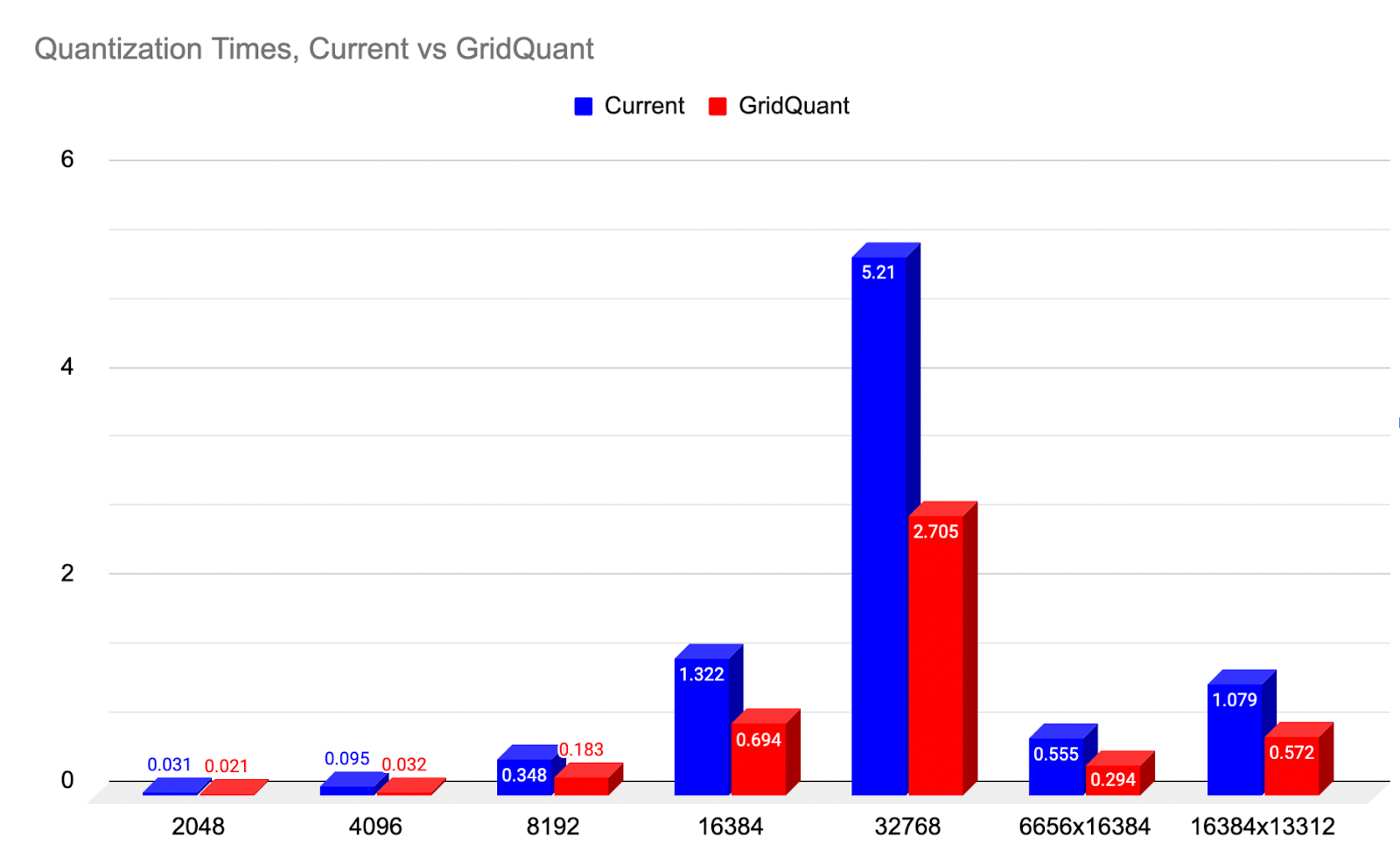

For the incoming quantization of A and B tensors from high precision (BFloat16) to Float8, we showcase GridQuant which leverages a mini-grid stride loop style of processing with nearly 2x speedups (99.31%) over a current 2D block quantization kernel.

For the Float8 GEMM, we showcase 3 new developments for Triton – Warp Specialization, TMA and a persistent kernel to effectively create a cooperative style kernel (an alternative to the Ping-Pong schedule). As a result, we achieve ~1.2x speedup over our best-performing SplitK kernel from last year.

Figure 1: A comparison of the 2D quantization speedup over a current baseline, across a range of sizes. (lower-is-better)

Why 2D Blockwise Quantization for FP8?

Generally speaking, the accuracy of fp8 quantization improves as we move from tensor-wise scaling, to row-wise scaling, to 2D block-wise, and then finally to column-wise scaling. This is because features for a given token are stored in each column, and thus each column in that tensor is more similarly scaled.

To minimize the number of outliers of a given numerical set, we want to find commonality so that numbers are being scaled in a similar fashion. For transformers, this means column based quantization could be optimal…however, columnar memory access is massively inefficient due to the data being laid out in memory in a rowwise contiguous manner. Thus columnwise loading would require memory access involving large strides in memory to pull isolated values, contrary to the core tenets of efficient memory access.

However, 2D is the next best option as it includes some aspects of columnar while being more memory efficient to pull since we can vectorize these loads with 2D vectorization. Therefore, we want to find ways to improve the speed for 2D block quantization which is why we developed the GridQuant kernel.

For the quantization process, we need to 2D block quantize both the higher precision BF16 incoming tensors (A = input activations, B = weights) and then proceed to do the Float8 matmul using the quantized tensors and their 2D block scaling values, and return an output C tensor in BF16.

How does GridQuant improve 2D block quantization efficiency?

The GridQuant kernel has several improvements over the initial baseline quantization implementation which was a standard tile based implementation. The GridQuant kernel has two full passes through the entire input tensor and works as follows:

Phase 1 – Determine the max abs value for each 256×256 sub block from the incoming high precision tensor.

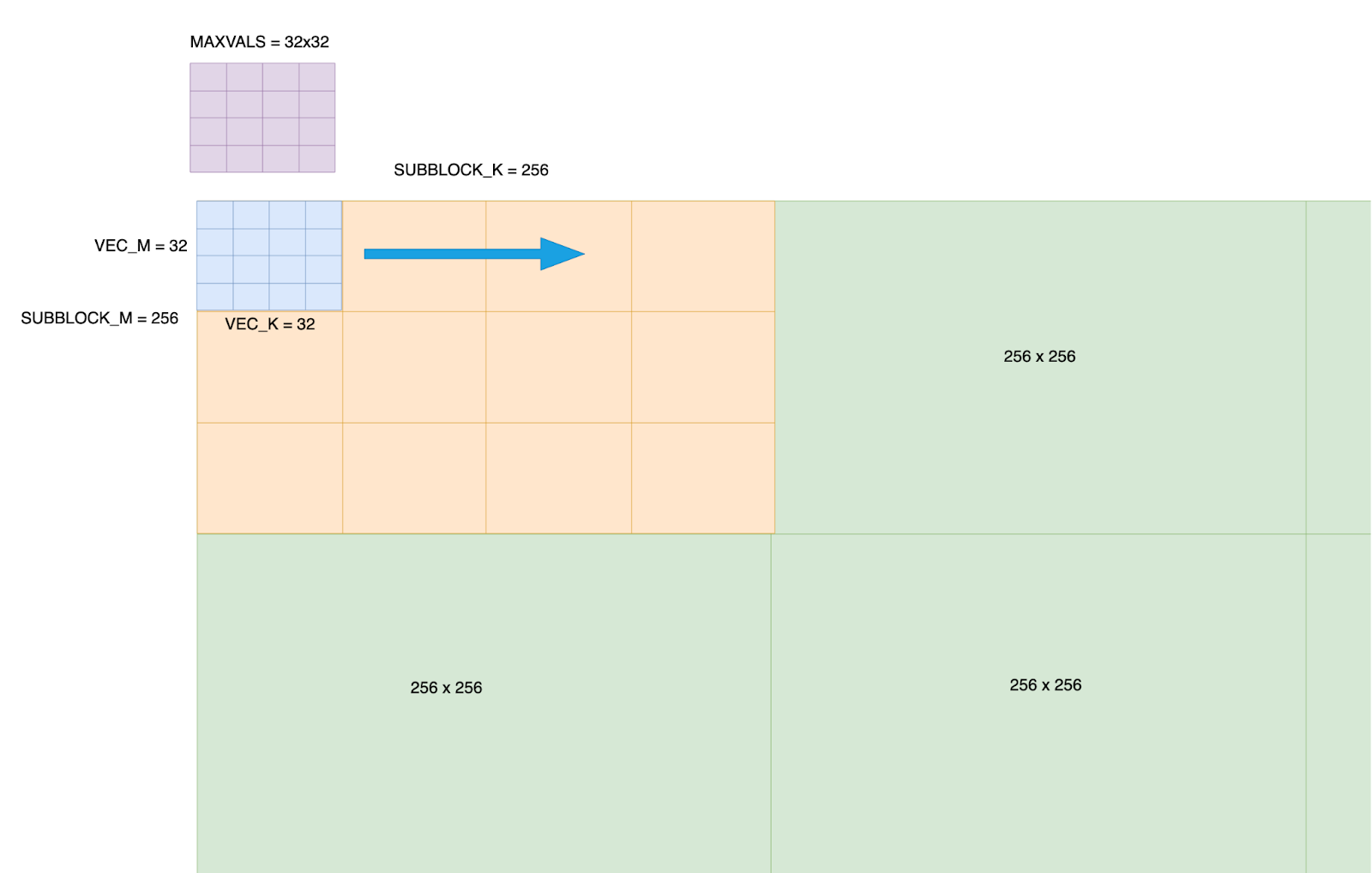

1 – We divide the BF16 tensor into 256 x 256 sub blocks. This quantization size is configurable, but 256×256 is the default as it provides a blend of quantization precision and processing efficiency.

2 – Each 256×256 sub-block is subdivided into 64 sub-blocks arranged in an 8×8 pattern, with each sub-block processing a 32×32 element block. A single warp (32 threads) handles the computation for all elements within its assigned 32×32 block.

3 – We declare a 32×32 max_vals array in shared memory. This will store the current max val for each position i,j as the 2d vector block moves across the entire 256×256 sub_block.

This is an important improvement because it means we can do vectorized, rather than scalar, updates to the max vals scoring system and allows for much more efficient updates.

Figure 2: The Fractionalized layout of an incoming tensor – a grid of 256×256 is created across the tensor, and within each 256×256 block, it is further refined into 32×32 sub blocks. A 32×32 max_vals is created for each 256×256 block.

4 – Each warp processes a 32×32 chunk and because we are using 4 warps, we ensure the Triton compiler can pipeline the memory loads for the next 32×32 chunk with the actual processing of absmax calculations for the current chunk. This ensures that the warp scheduler is able to toggle warps loading data with those processing and keep the SM continuously busy.

5 – The 32×32 2D vector block processing is moved across and through the entire 256×256 subblock in a grid stride looping fashion, with each warp updating the shared memory 32×32 max_vals against its current 32×32 sub-block. Thus max_vals[i,j] holds the latest max value as each sub block is processed.

After completing the 256×256 block grid stride loop, the maxvals matrix is then itself reduced to find the absolute single max value for that entire 256 block.

This gives us our final scaling factor value for this 2D 256 x 256 block.

Phase 2 – Quantize the 256×256 block values to Float8, by using the single max value scaling factor found during Phase 1.

Next, we make a second pass through the entire 256×256 block to rescale all the numbers using this max value found in phase 1 to convert them to the float 8 format.

Because we know we need to do 2 complete passes, for the loads during the phase 1 portion we instruct the triton compiler to keep these values in cache at higher priority (evict policy = last).

This means that during the second pass, we can get a high hit rate from the L2 cache which provides much faster memory access than going all the way to HBM.

With the 2D block quantization processing complete when all 256 x256 blocks are processed, we can return the new Float8 quantized tensor along with it’s scaling factor matrix, which we’ll use in the next phase of the GEMM processing. This input quantization is repeated for the second input tensor as well, meaning we end up with A_Float 8, A_scaling_matrix, and B_Float8 and B_scaling matrix.

GridQuant – GEMM Kernel

The GridQuant-GEMM kernel takes in the four outputs from the quantization above for processing. Our high-performance GEMM kernel features several new Triton developments to achieve SOTA performance for matrix shape profiles relevant in LLM inference during the decoding phase.

These new features are commonly found in Hopper optimized kernels like FlashAttention-3 and Machete, built using CUTLASS 3.x. Here, we discuss these methods and showcase the performance benefits that can be achieved leveraging them in Triton.

Tensor Memory Accelerator (TMA)

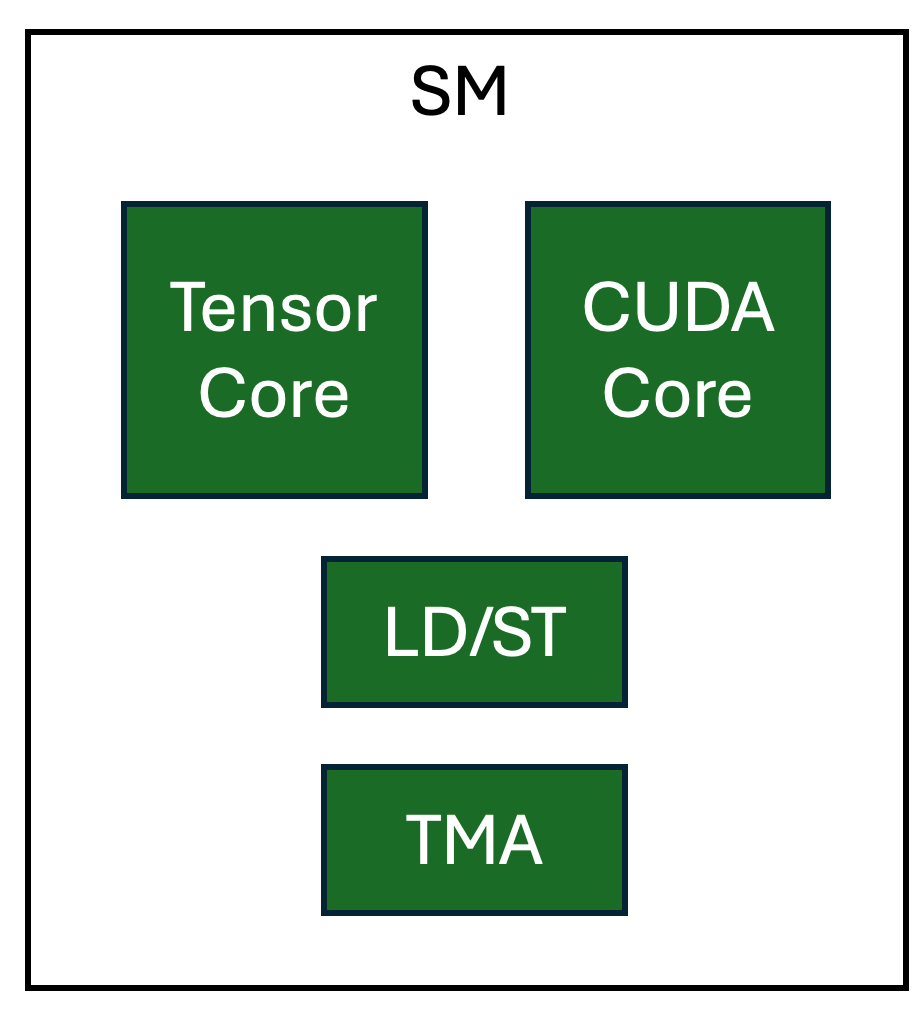

The TMA unit on NVIDIA Hopper GPUs, is a dedicated hardware unit for load/store operations that act on multidimensional tensors commonly found in AI workloads. This has several important benefits.

Transferring data from global and shared memory can occur without involving other resources on GPU SMs, freeing up registers and CUDA Cores. Further, when used in warp-specialized kernels, light-weight TMA operations can be assigned to a producer warp allowing for a high degree of overlap of memory transfers and computation.

For more details on how TMA is used in Triton see our previous blog.

Warp-Specialization (Cooperative Persistent Kernel Design)

Warp Specialization is a technique to leverage pipeline parallelism on GPUs. This experimental feature enables the expression of specialized threads through a tl.async_task API, allowing the user to specify how operations in a Triton program should be “split” amongst warps. The cooperative Triton kernel performs different types of computation and loads that each take place on their own dedicated hardware. Having dedicated hardware for each of these specialized tasks makes it possible to realize parallelism efficiently for operations that have no data dependency.

Figure 3. Logical view of dedicated HW units in NVIDIA H100 SM

The operations in our kernel that create the pipeline are:

A – Load per-block scale from GMEM into SMEM (cp.async engine)

B – Load activation (A) and Weight (B) tiles from GMEM into SMEM (TMA)

C – Matrix-Multiplication of A tile and B tile = C tile (Tensor Core)

D – Scale C tile with per-block scale from A and per-block scale from B (CUDA core)

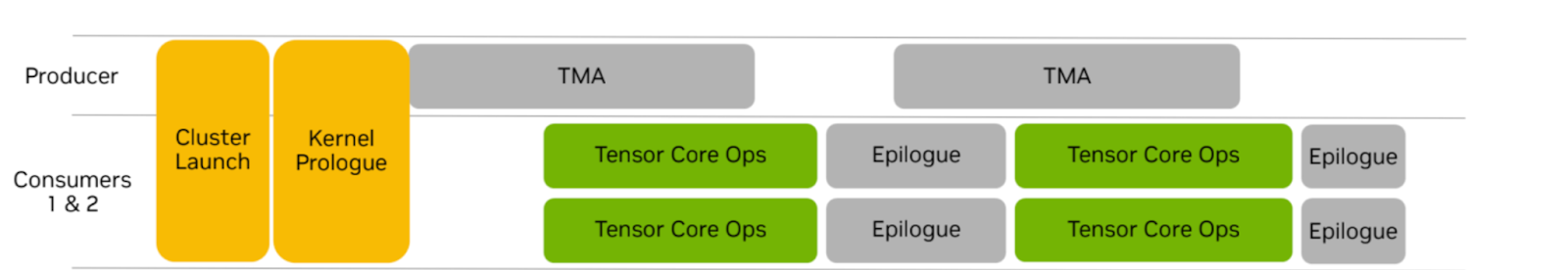

These steps can be assigned to “tasks” which are carried out by specialized warp groups in a threadblock. The cooperative strategy has three warp groups. A producer warp group that is responsible for feeding the compute units and 2 consumer warp groups that perform the computation. The two consumer warp groups each work on half of the same output tile.

Figure 4. Warp-Specialized Persistent Cooperative kernel (source: NVIDIA)

This is different from the ping-pong schedule we discussed in our previous blog, where each consumer warp group works on different output tiles. We note that the Tensor Core ops are not overlapped with the epilogue computation. Decreased utilization of the Tensor Core pipeline during the epilogue phase of the computation will reduce register pressure for the consumer warp group compared to ping-pong which always keeps the Tensor Core busy, thus allowing for larger tile sizes.

Lastly, our kernel is designed to be persistent when the grid size exceeds the number of available compute units on H100 GPUs (132). Persistent kernels remain active on the GPU for an extended period and compute multiple output tiles during its lifetime. Our kernel leverages TMA async shared to global memory stores, while continuing to do work on the next output tile as opposed to incurring the cost of scheduling multiple threadblocks.

Microbenchmarks

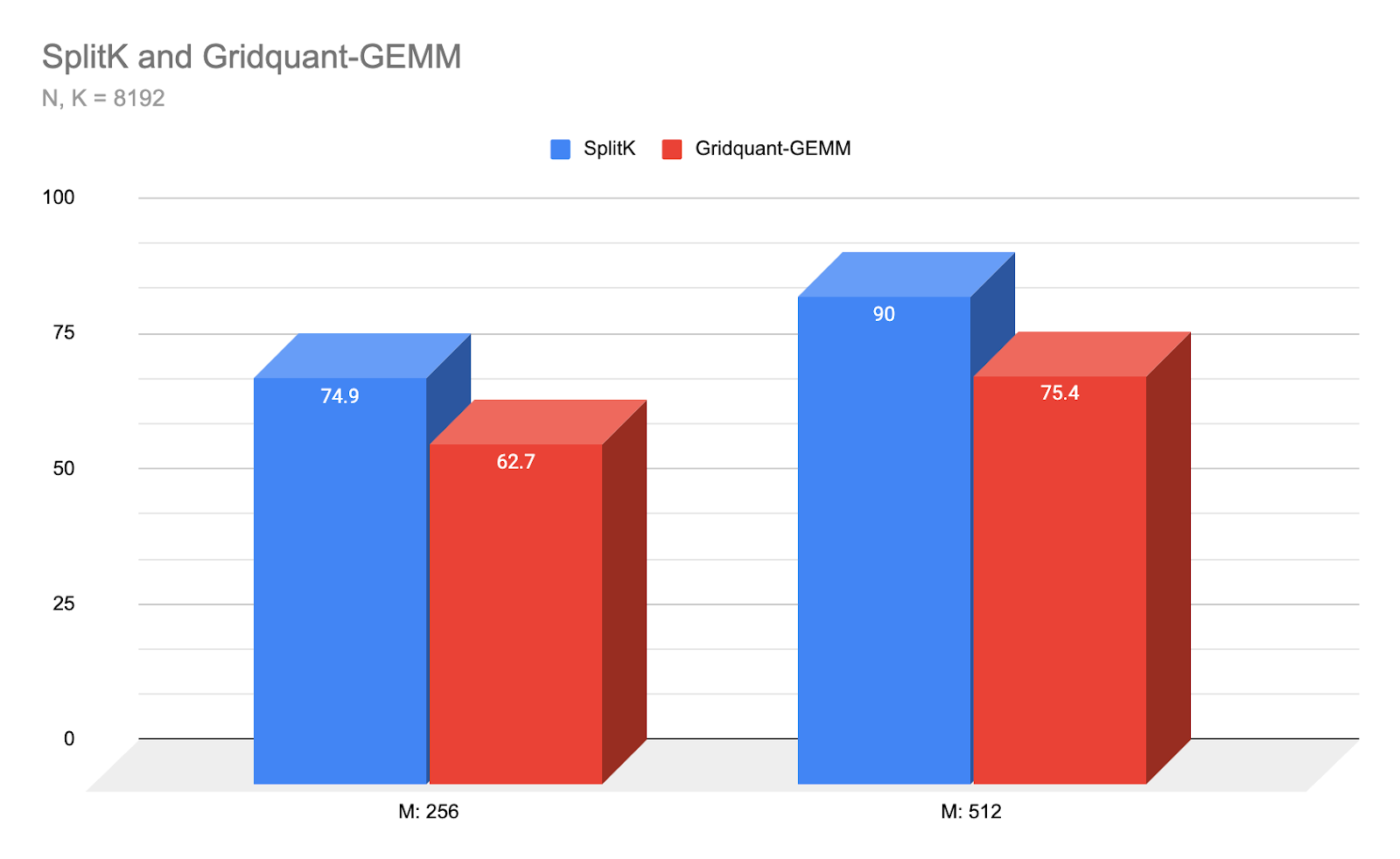

Figure 5: Latency comparison (us) of Gridquant-GEMM vs our best performing SplitK kernel for small batch regime and Llama3 8192 N,K sizing. (lower-is-better)

The Warp-Specialized Triton kernel achieves SOTA performance at the above small-M and square matrix shapes, achieving a nearly 1.2x speedup over the SplitK Triton kernel, which was the previous best performing strategy for Triton GEMMs in this low arithmetic intensity regime. For future work, we plan to tune our kernel performance for the medium-to-large M regime and non-square matrices.

Conclusion and Future Work

Future work includes benchmarking gridquant on end to end workflows. In addition, we plan to run more extensive benchmarks on non-square (rectangular) matrices as well as medium-to-large M sizes. Finally, we plan to explore ping-pong style warp-specialization in Triton versus the current cooperative implementation.