Our method learns complex behaviors by training offline from prior datasets

(expert demonstrations, data from previous experiments, or random exploration

data) and then fine-tuning quickly with online interaction.

Robots trained with reinforcement learning (RL) have the potential to be used

across a huge variety of challenging real world problems. To apply RL to a new

problem, you typically set up the environment, define a reward function, and

train the robot to solve the task by allowing it to explore the new environment

from scratch. While this may eventually work, these “online” RL methods are

data hungry and repeating this data inefficient process for every new problem

makes it difficult to apply online RL to real world robotics problems. What if

instead of repeating the data collection and learning process from scratch

every time, we were able to reuse data across multiple problems or experiments?

By doing so, we could greatly reduce the burden of data collection with every

new problem that is encountered. With hundreds to thousands of robot

experiments being constantly run, it is of crucial importance to devise an RL

paradigm that can effectively use the large amount of already available data

while still continuing to improve behavior on new tasks.

The first step towards moving RL towards a data driven paradigm is to consider

the general idea of offline (batch) RL. Offline RL considers the problem of

learning optimal policies from arbitrary off-policy data, without any further

exploration. This is able to eliminate the data collection problem in RL, and

incorporate data from arbitrary sources including other robots or

teleoperation. However, depending on the quality of available data and the

problem being tackled, we will often need to augment offline training with

targeted online improvement. This problem setting actually has unique

challenges of its own. In this blog post, we discuss how we can move RL from

training from scratch with every new problem to a paradigm which is able to

reuse prior data effectively, with some offline training followed by online

finetuning.

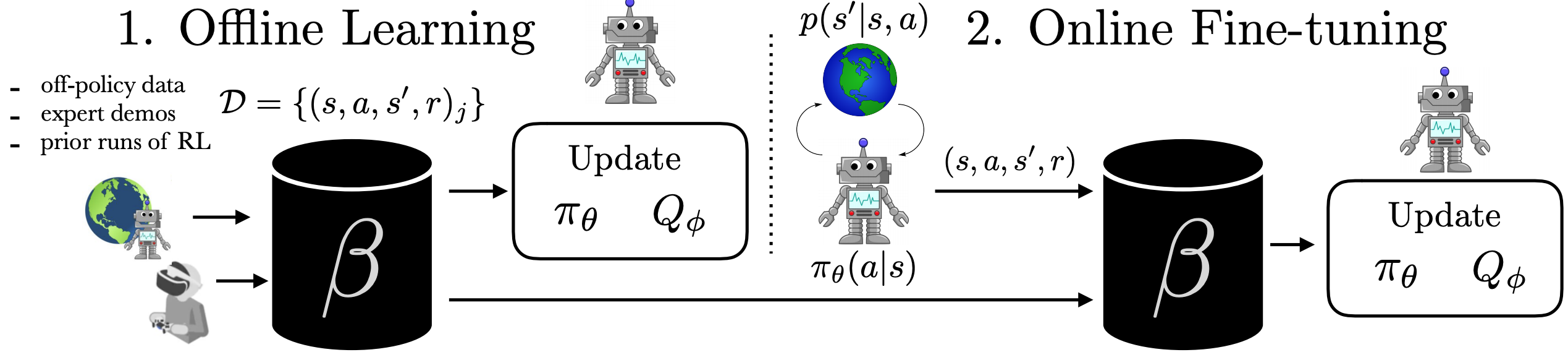

Figure 1: The problem of accelerating online RL with offline datasets. In

(1), the robot learns a policy entirely from an offline dataset. In (2), the

robot gets to interact with the world and collect on-policy samples to improve

the policy beyond what it could learn offline.

Challenges in Offline RL with Online Fine-tuning

We analyze the challenges in the problem of learning from offline data and

subsequent fine-tuning, using the standard benchmark HalfCheetah locomotion

task. The following experiments are conducted with a prior dataset consisting

of 15 demonstrations from an expert policy and 100 suboptimal trajectories

sampled from a behavioral clone of these demonstrations.

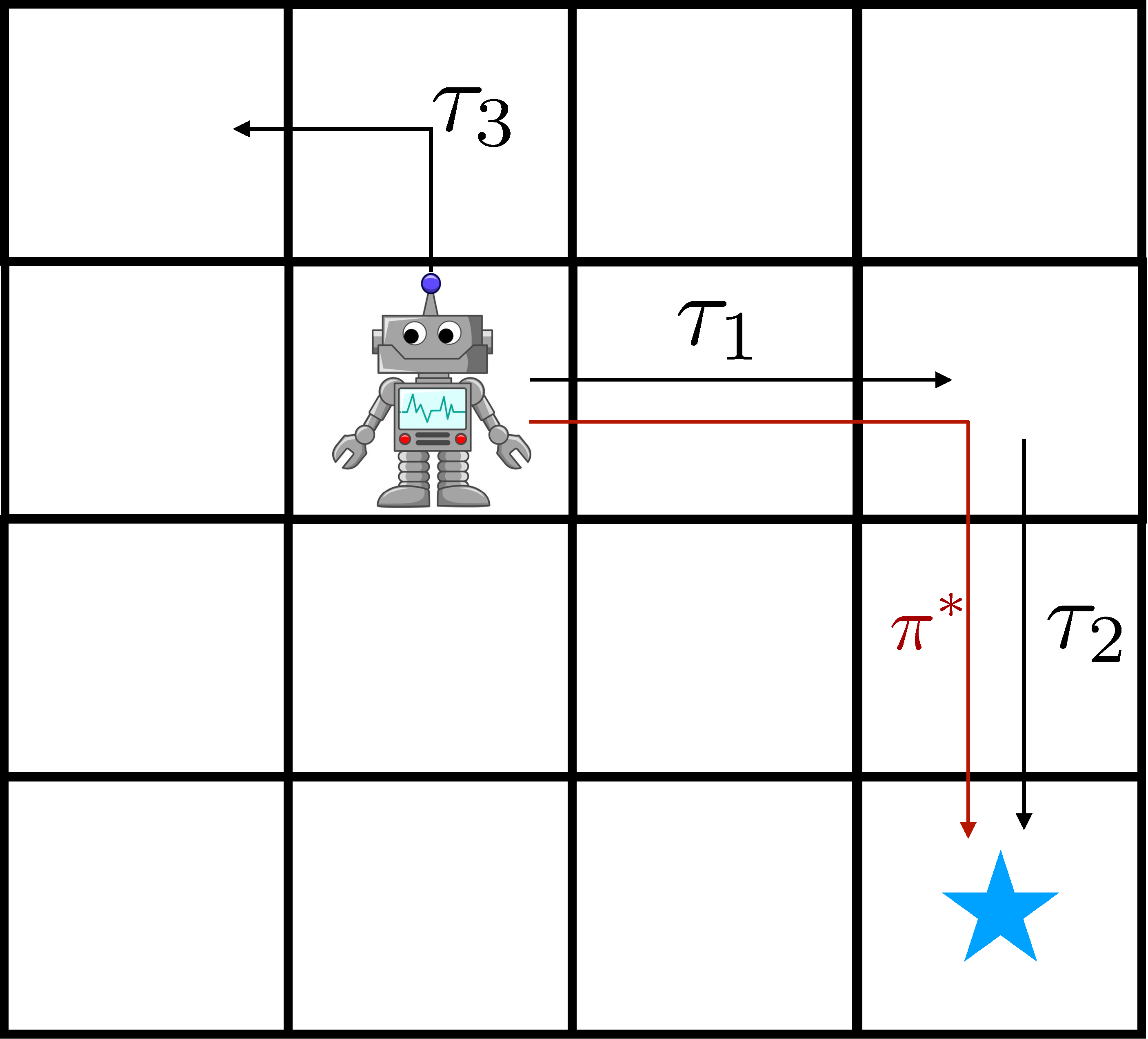

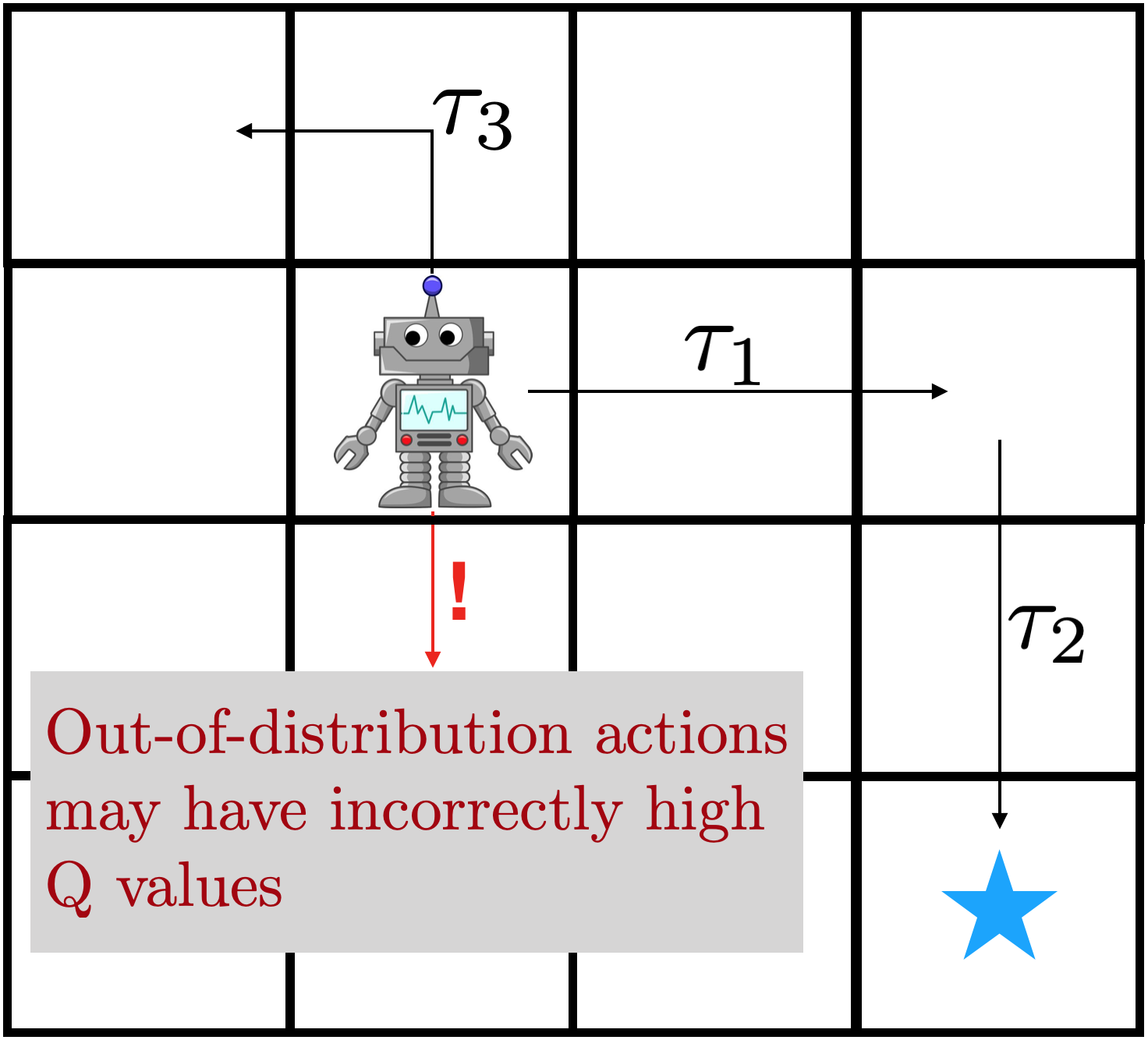

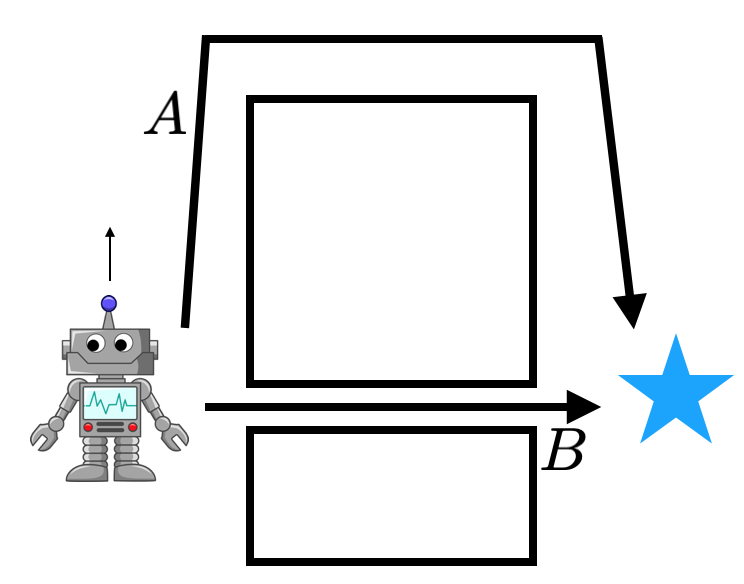

Figure 2: On-policy methods are slow to learn compared to off-policy

methods, due to the ability of off-policy methods to “stitch” good trajectories

together, illustrated on the left. Right: in practice, we see slow online

improvement using on-policy methods.

1. Data Efficiency

A simple way to utilize prior data such as demonstrations for RL is to

pre-train a policy with imitation learning, and fine-tune with on-policy RL

algorithms such as AWR or DAPG.

This has two drawbacks. First, the prior data may not be optimal so imitation

learning may be ineffective. Second, on-policy fine-tuning is data inefficient

as it does not reuse the prior data in the RL stage. For real-world robotics,

data efficiency is vital. Consider the robot on the right, trying to reach the

goal state with prior trajectory $tau_1$ and $tau_2$. On-policy methods

cannot effectively use this data, but off-policy algorithms that do dynamic

programming can, by effectively “stitching” $tau_1$ and $tau_2$ together with

the use of a value function or model. This effect can be seen in the learning

curves in Figure 2, where on-policy methods are an order of magnitude slower

than off-policy actor-critic methods.

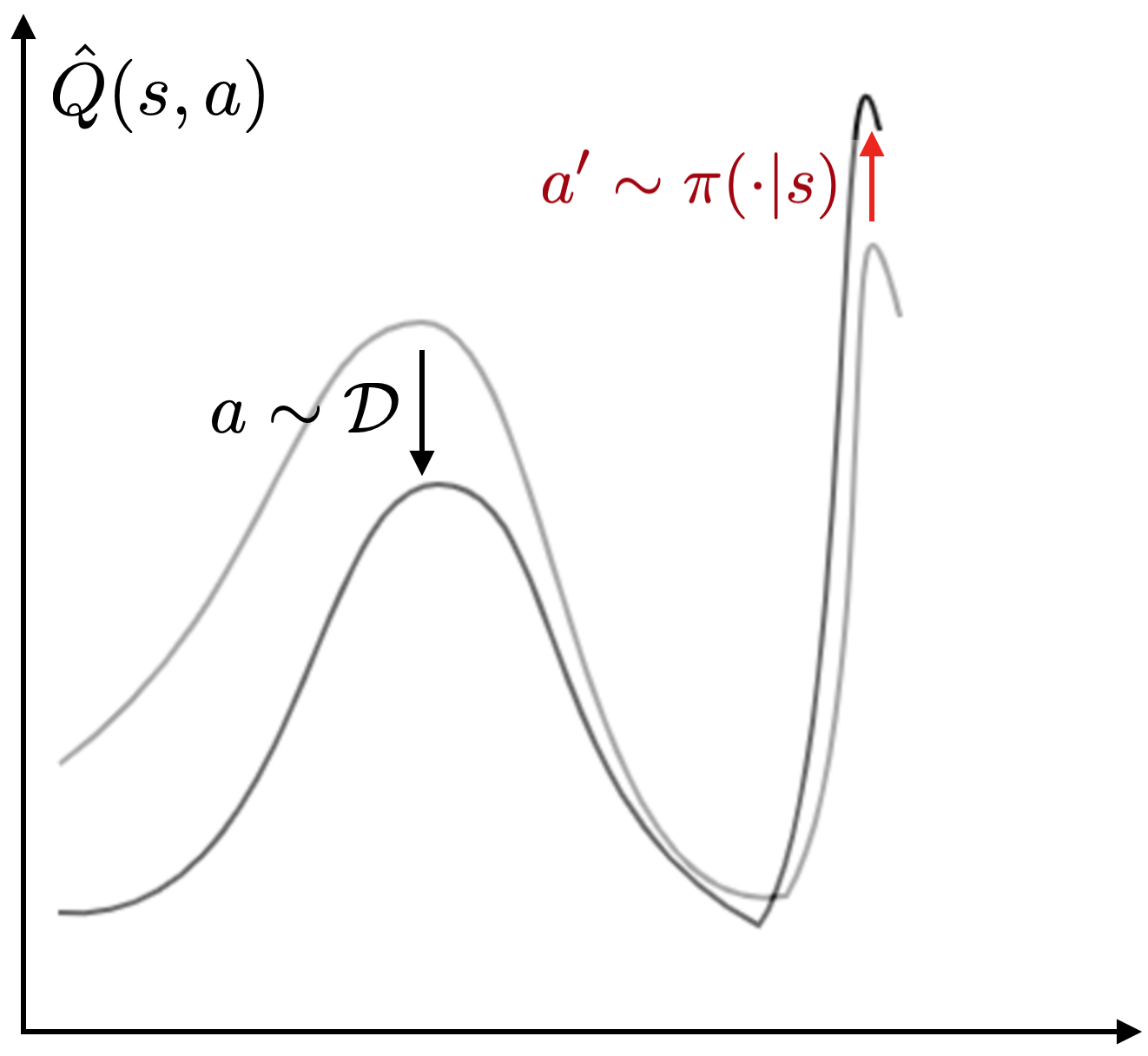

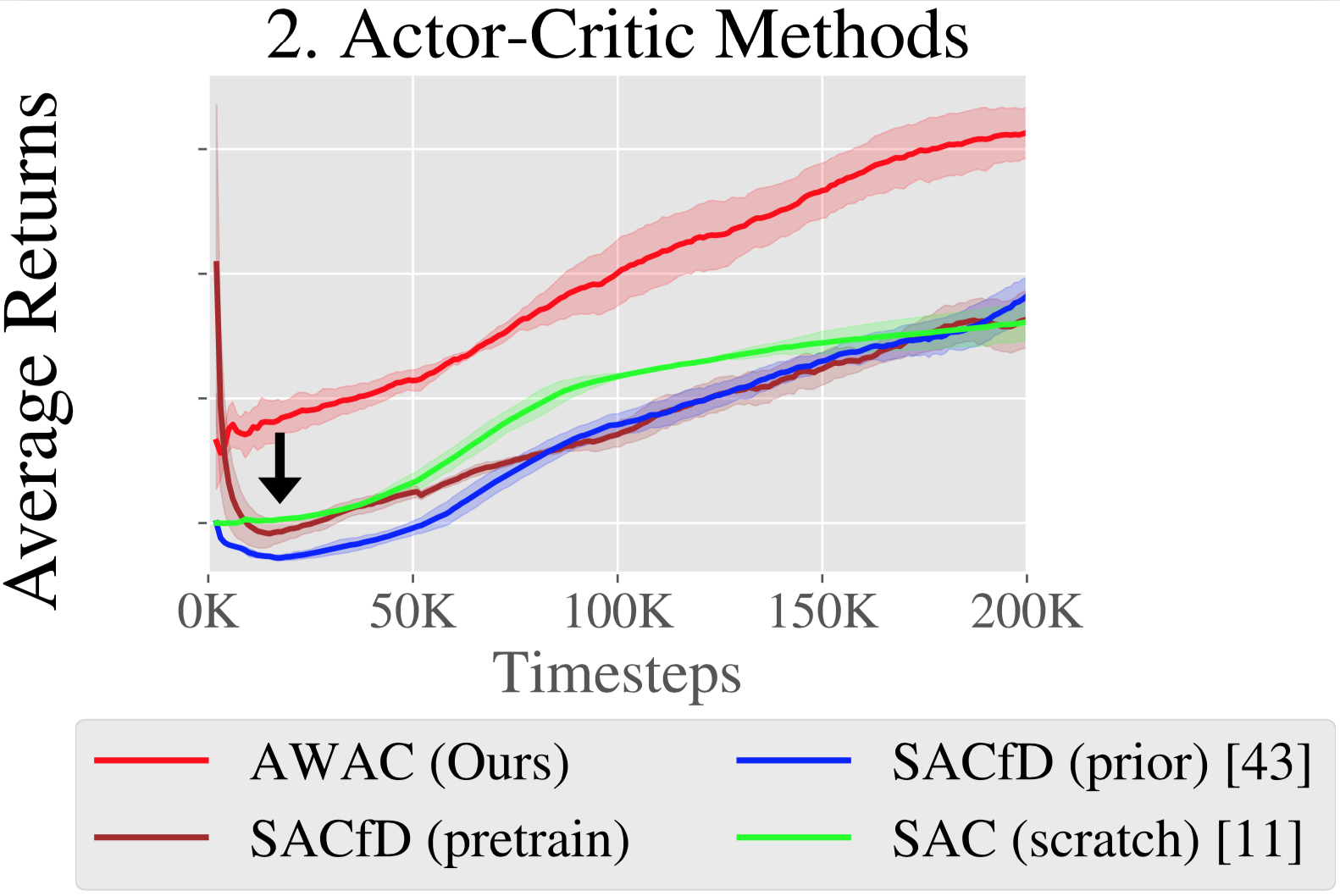

Figure 3: Bootstrapping error is an issue when using off-policy RL for

offline training. Left: an erroneous Q value far away from the data is

exploited by the policy, resulting in a poor update of the Q function. Middle:

as a result, the robot may take actions that are out of distribution. Right:

bootstrap error causes poor offline pretraining when using SAC and its

variants.

2. Bootstrapping Error

Actor-critic methods can in principle learn efficiently from off-policy data by

estimating a value estimate $V(s)$ or action-value estimate $Q(s, a)$ of future

returns by Bellman bootstrapping. However, when standard off-policy

actor-critic methods are applied to our problem (we use SAC), they perform poorly, as shown

in Figure 3: despite having a prior dataset in the replay buffer, these

algorithms do not benefit significantly from offline training (as seen by the

comparison between the SAC(scratch) and SACfD(prior) lines in Figure 3).

Moreover, even if the policy is pre-trained by behavior cloning (“SACfD

(pretrain)”) we still observe an initial decrease in performance.

This challenge can be attributed to off-policy bootstrapping error

accumulation. During training, the Q estimates will not be fully accurate,

particularly in extrapolating actions that are not present in the data. The

policy update exploits overestimated Q values, making the estimated Q values

worse. The issue is illustrated in the figure: incorrect Q values result in an

incorrect update to the target Q values, which may result in the robot taking a

poor action.

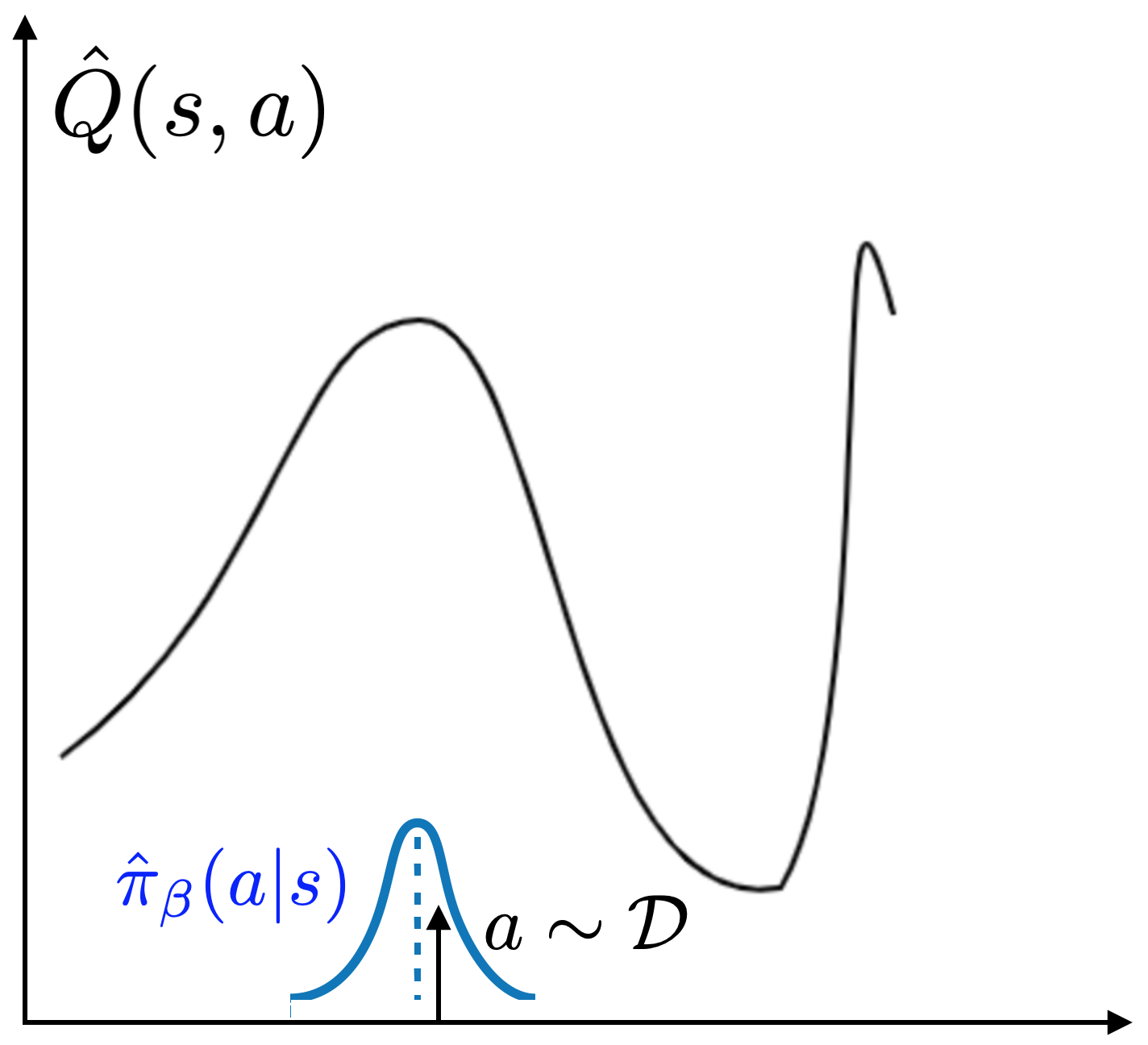

3. Non-stationary Behavior Models

Prior offline RL algorithms such as BCQ, BEAR, and BRAC propose to address the

bootstrapping issue by preventing the policy from straying too far from the

data. The key idea is to prevent bootstrapping error by constraining the policy

$pi$ close to the “behavior policy” $pi_beta$: the actions that are present

in the replay buffer. The idea is illustrated in the figure below: by sampling

actions from $pi_beta$, you avoid exploiting incorrect Q values far away from

the data distribution.

However, $pi_beta$ is typically not known, especially for offline data, and

must be estimated from the data itself. Many offline RL algorithms (BEAR, BCQ,

ABM) explicitly fit a parametric

model to samples from the replay buffer for the distribution $pi_beta$. After

forming an estimate $hat{pi}_beta$, prior methods implement the policy

constraint in various ways, including penalties on the policy update (BEAR,

BRAC) or architecture choices for sampling actions for policy training (BCQ,

ABM).

While offline RL algorithms with constraints perform well offline, they

struggle to improve with fine-tuning, as shown in the third plot in Figure 1.

We see that the purely offline RL performance (at “0K” in Fig.1) is much

better than SAC. However, with additional iterations of online fine-tuning, the

performance increases very slowly (as seen from the slope of the BEAR curve in

Fig 1). What causes this phenomenon?

The issue is in fitting an accurate behavior model as data is collected online

during fine-tuning. In the offline setting, behavior models must only be

trained once, but in the online setting, the behavior model must be updated

online to track incoming data. Training density models online (in the

“streaming” setting) is a challenging research problem, made more difficult by

a potentially complex multi-modal behavior distribution induced by the mixture

of online and offline data. In order to address our problem setting, we require

an off-policy RL algorithm that constrains the policy to prevent offline

instability and error accumulation, but is not so conservative that it prevents

online fine-tuning due to imperfect behavior modeling. Our proposed algorithm,

which we discuss in the next section, accomplishes this by employing an

implicit constraint, which does not require any explicit modeling of the

behavior policy.

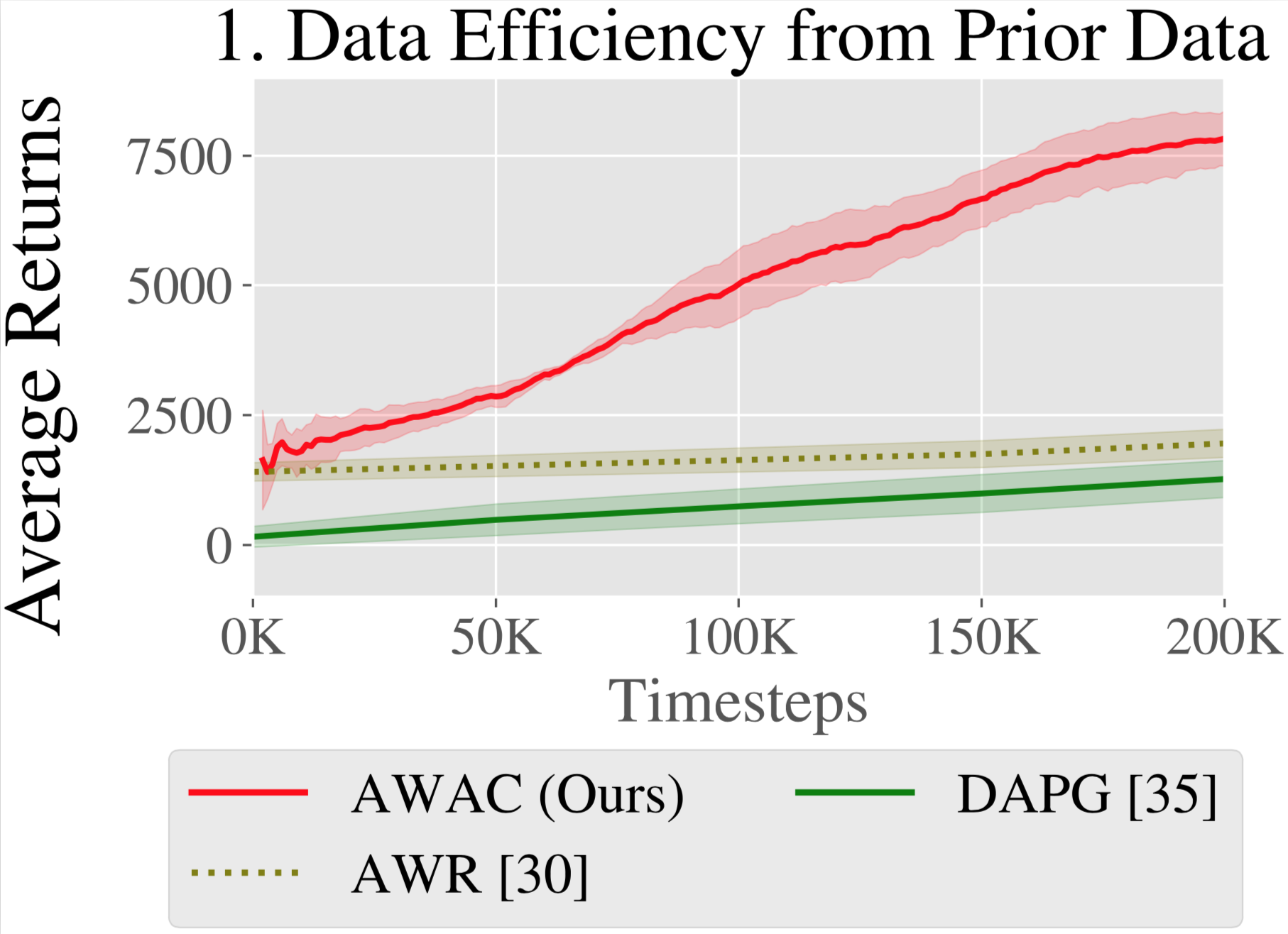

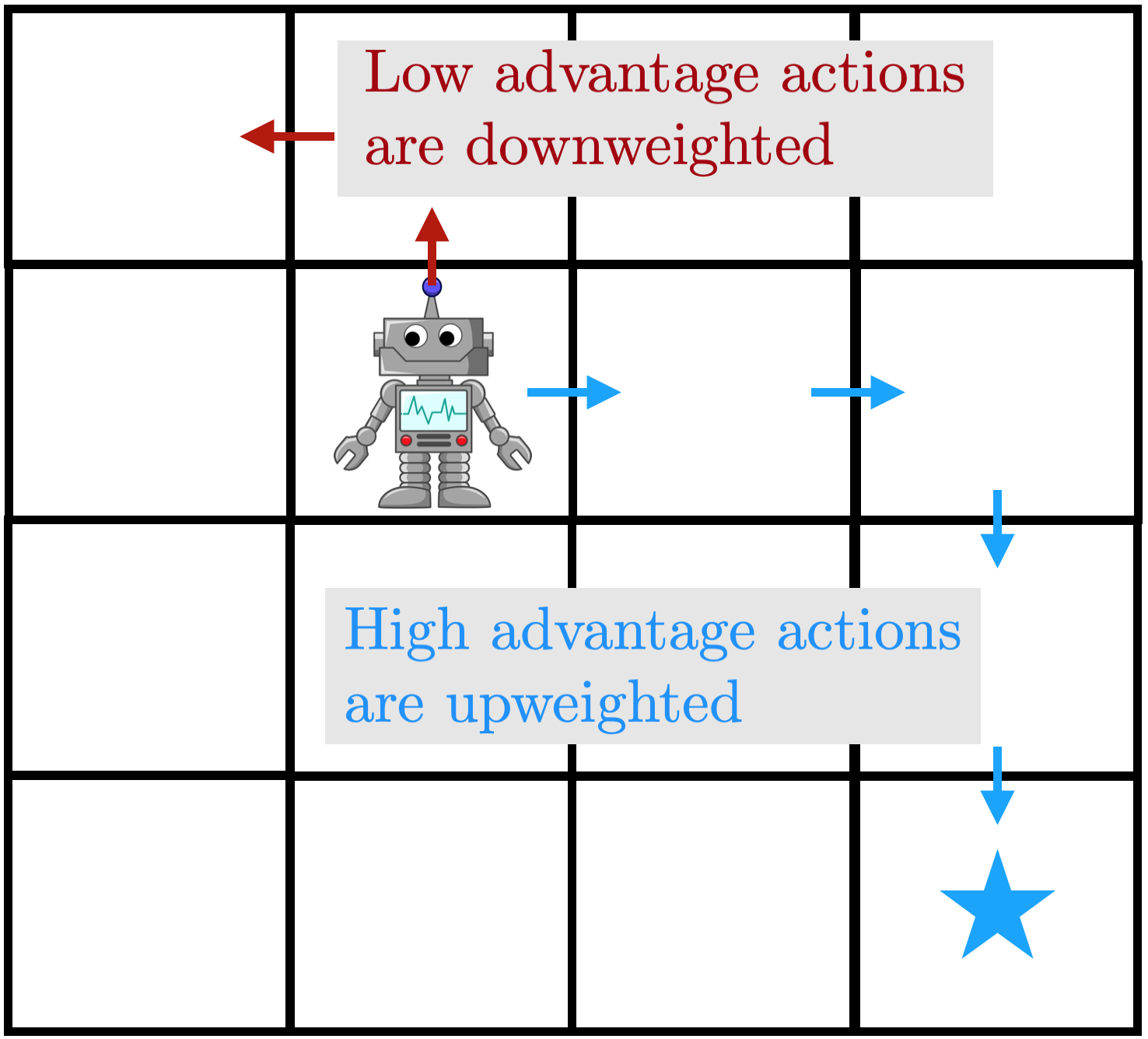

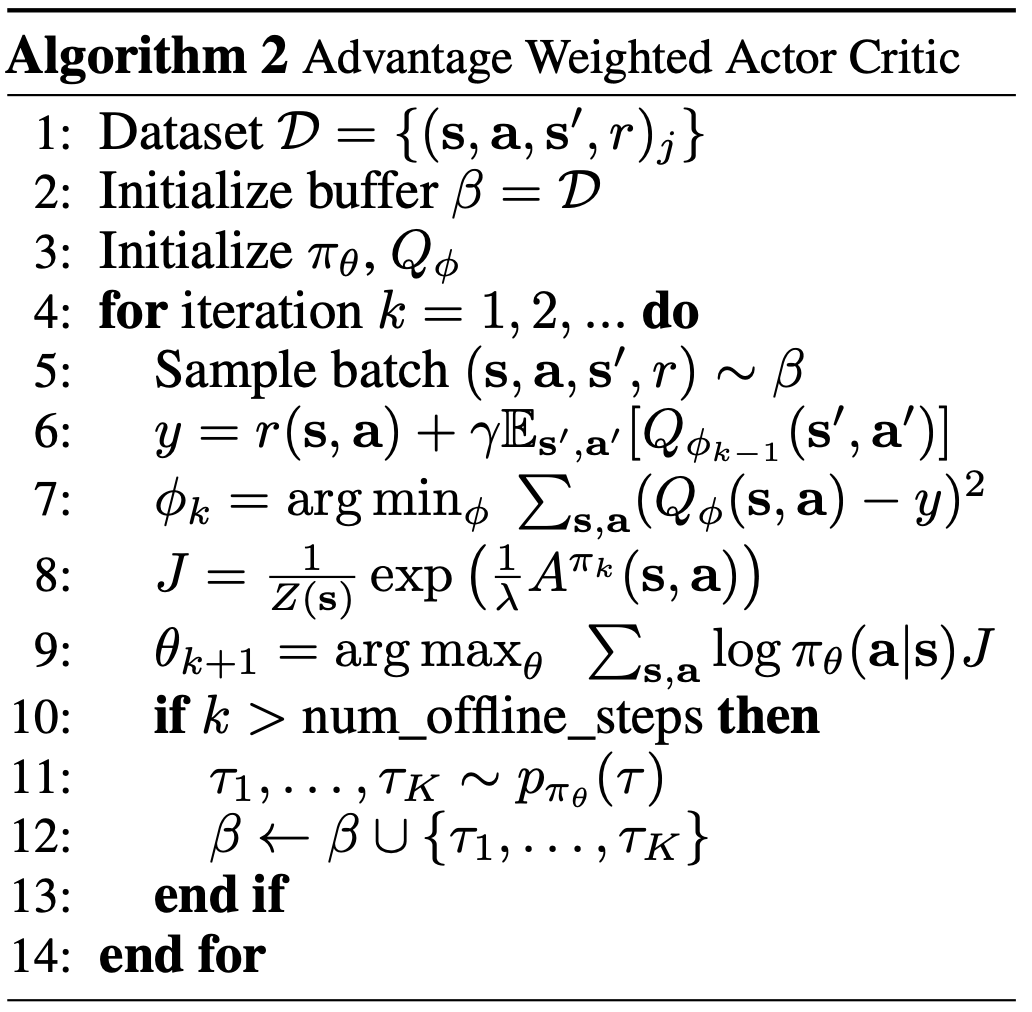

Figure 4: an illustration of AWAC. High-advantage transitions are regressed

on with high weight, while low advantage transitions have low weight. Right:

algorithm pseudocode.

Advantage Weighted Actor Critic

In order to avoid these issues, we propose an extremely simple algorithm –

advantage weighted actor critic (AWAC). AWAC avoids the pitfalls in the

previous section with careful design decisions. First, for data efficiency, the

algorithm trains a critic that is trained with dynamic programming. Now, how

can we use this critic for offline training while avoiding the bootstrapping

problem, while also avoiding modeling the data distribution, which may be

unstable? For avoiding bootstrapping error, we optimize the following problem:

We can compute the optimal solution for this equation and project our policy

onto it, which results in the following actor update:

This results in an intuitive actor update, that is also very effective in

practice. The update resembles weighted behavior cloning; if the Q function was

uninformative, it reduces to behavior cloning the replay buffer. But with a

well-formed Q estimate, we weight the policy towards only good actions. An

illustration is given in the figure above: the agent regresses onto

high-advantage actions with a large weight, while almost ignoring low-advantage

actions. Please see the paper for an expanded derivation and implementation

details.

Experiments

So how well does this actually do at addressing our concerns from earlier? In

our experiments, we show that we can learn difficult, high-dimensional, sparse

reward dexterous manipulation problems from human demonstrations and off-policy

data. We then evaluate our method with suboptimal prior data generated by a

random controller. Results on standard MuJoCo benchmark environments

(HalfCheetah, Walker, and Ant) are also included in the paper.

Dexterous Manipulation

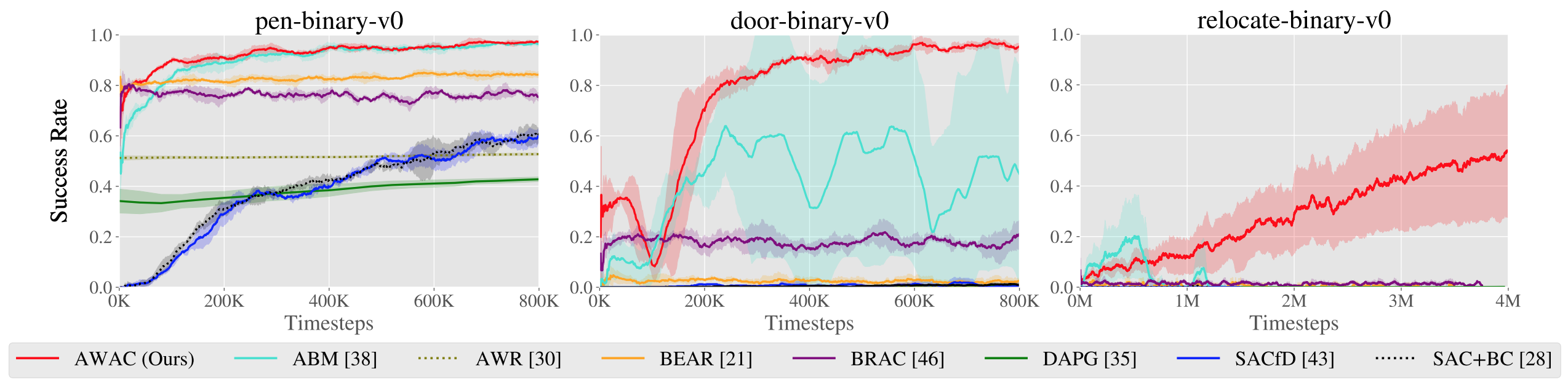

Figure 5. Top: performance shown for various methods after online training

(pen: 200K steps, door: 300K steps, relocate: 5M steps). Bottom: learning

curves on dextrous manipulation tasks with sparse rewards are shown. Step 0

corresponds to the start of online training after offline pre-training.

We aim to study tasks representative of the difficulties of real-world robot

learning, where offline learning and online fine-tuning are most relevant. One

such setting is the suite of dexterous manipulation tasks proposed by Rajeswaran et al., 2017. These

tasks involve complex manipulation skills using a 28-DoF five-fingered hand in

the MuJoCo simulator: in-hand rotation of a pen, opening a door by unlatching

the handle, and picking up a sphere and relocating it to a target location.

These environments exhibit many challenges: high dimensional action spaces,

complex manipulation physics with many intermittent contacts, and randomized

hand and object positions. The reward functions in these environments are

binary 0-1 rewards for task completion. Rajeswaran et al. provide 25 human

demonstrations for each task, which are not fully optimal but do solve the

task. Since this dataset is very small, we generated another 500 trajectories

of interaction data by constructing a behavioral cloned policy, and then

sampling from this policy.

First, we compare our method on the dexterous manipulation tasks described

earlier against prior methods for off-policy learning, offline learning, and

bootstrapping from demonstrations. The results are shown in the figure above.

Our method uses the prior data to quickly attain good performance, and the

efficient off-policy actor-critic component of our approach fine-tunes much

quicker than DAPG. For example, our method solves the pen task in 120K

timesteps, the equivalent of just 20 minutes of online interaction. While the

baseline comparisons and ablations are able to make some amount of progress on

the pen task, alternative off-policy RL and offline RL algorithms are largely

unable to solve the door and relocate task in the time-frame considered. We

find that the design decisions to use off-policy critic estimation allow AWAC

to significantly outperform AWR while the implicit behavior modeling allows

AWAC to significantly outperform ABM, although ABM does make some progress.

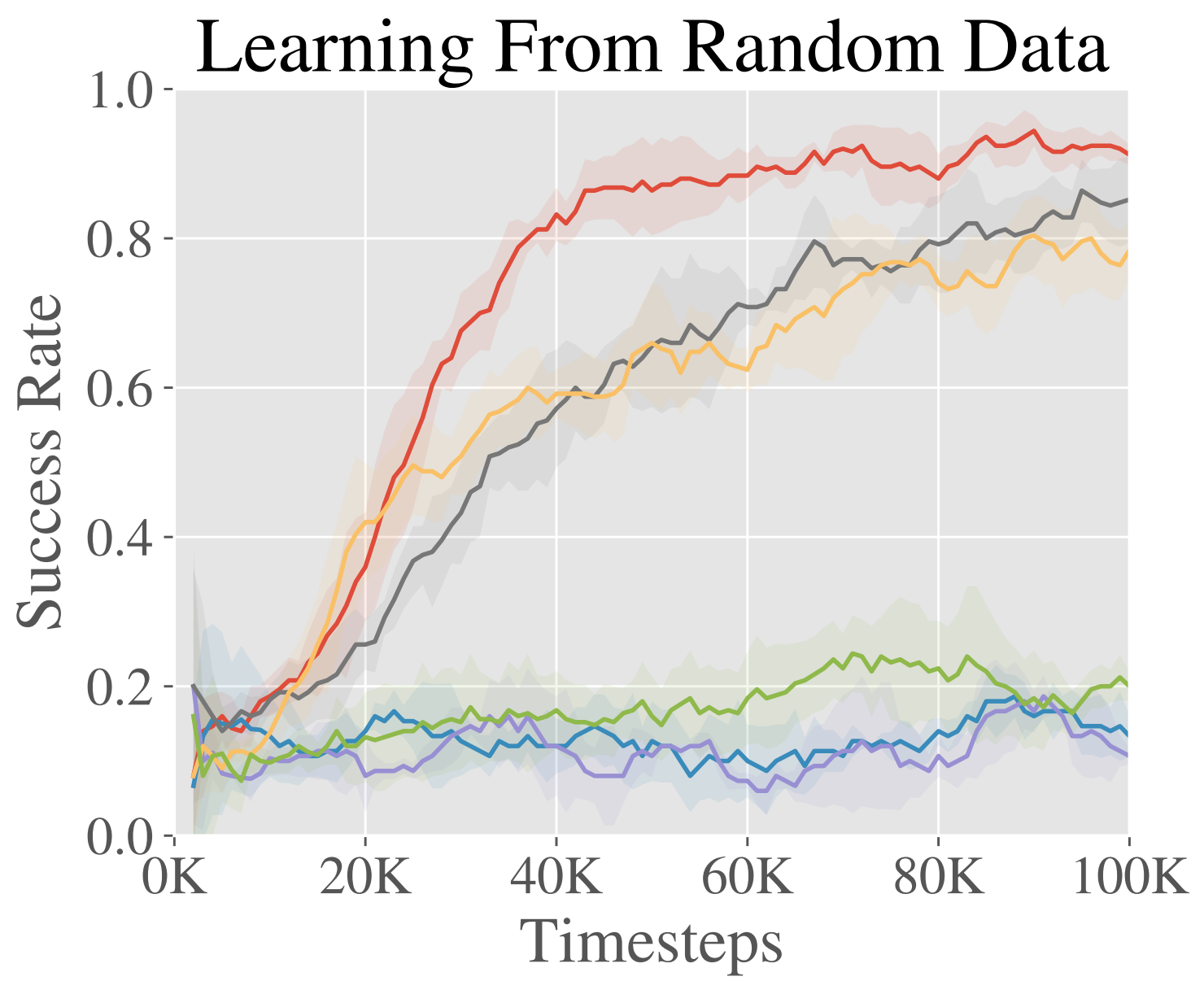

Fine-Tuning from Random Policy Data

An advantage of using off-policy RL for reinforcement learning is that we can

also incorporate suboptimal data, rather than only demonstrations. In this

experiment, we evaluate on a simulated tabletop pushing environment with a

Sawyer robot.

To study the potential to learn from suboptimal data, we use an off-policy

dataset of 500 trajectories generated by a random process. The task is to push

an object to a target location in a 40cm x 20cm goal space.

The results are shown in the figure to the right. We see that while many

methods begin at the same initial performance, AWAC learns the fastest online

and is actually able to make use of the offline dataset effectively as opposed

to some methods which are completely unable to learn.

Future Directions

Being able to use prior data and fine-tune quickly on new problems opens up

many new avenues of research. We are most excited about using AWAC to move from

the single-task regime in RL to the multi-task regime, with data sharing and

generalization between tasks. The strength of deep learning has been its

ability to generalize in open-world settings, which we have already seen

transform the fields of computer vision and natural language processing. To

achieve the same type of generalization in robotics, we will need RL algorithms

that take advantage of vast amounts of prior data. But one key distinction in

robotics is that collecting high-quality data for a task is very difficult –

often as difficult as solving the task itself. This is opposed to, for instance

computer vision, where humans can label the data. Thus, the active data

collection (online learning) will be an important piece of the puzzle.

This work also suggests a number of algorithmic directions to move forward.

Note that in this work we focused on mismatched action distributions between

the policy $pi$ and the behavior data $pi_beta$. When doing off-policy

learning, there is also a mismatched marginal state distribution between the

two. Intuitively, consider a problem with two solutions A and B, with B being a

higher return solution and off-policy data demonstrating solution A provided.

Even if the robot discovers solution B during online exploration, the

off-policy data still consists of mostly data from path A. Thus the Q-function

and policy updates are computed over states encountered while traversing path A

even though it will not encounter these states when executing the optimal

policy. This problem has been studied previously. Accounting for both

types of distribution mismatch will likely result in better RL algorithms.

Finally, we are already using AWAC as a tool to speed up our research. When we

set out to solve a task, we do not usually try to solve it from scratch with

RL. First, we may teleoperate the robot to confirm the task is solvable; then

we might run some hard-coded policy or behavioral cloning experiments to see if

simple methods can already solve it. With AWAC, we can save all of the data in

these experiments, as well as other experimental data such as when

hyperparameter sweeping an RL algorithm, and use it as prior data for RL.

A preprint of the work this blog post is based on is available here. Code is now included in rlkit. The code documentation also

contains links to the data and environments we used. The project website is

available here.