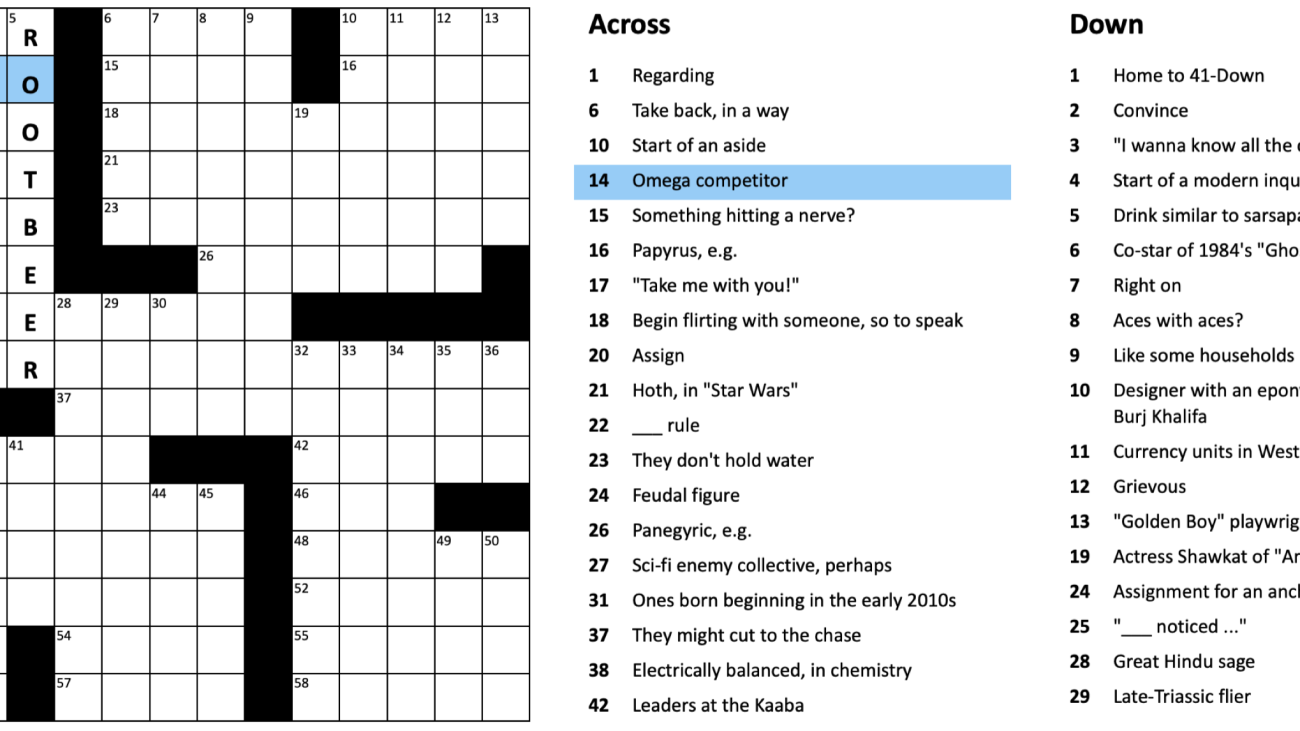

We recently published the Berkeley Crossword Solver (BCS), the current state of the art for solving American-style crossword puzzles. The BCS combines neural question answering and probabilistic inference to achieve near-perfect performance on most American-style crossword puzzles, like the one shown below:

Figure 1: Example American-style crossword puzzle

An earlier version of the BCS, in conjunction with Dr.Fill, was the first computer program to outscore all human competitors in the world’s top crossword tournament. The most recent version is the current top-performing system on crossword puzzles from The New York Times, achieving 99.7% letter accuracy (see the technical paper, web demo, and code release).