Editor’s note: Today we’re building on our long-standing partnership with the University of Cambridge, with a multi-year research collaboration agreement and a Google gr…Read More

Editor’s note: Today we’re building on our long-standing partnership with the University of Cambridge, with a multi-year research collaboration agreement and a Google gr…Read More

Improving traffic evacuations: A case study

Some cities or communities develop an evacuation plan to be used in case of an emergency. There are a number of reasons why city officials might enact their plan, a primary one being a natural disaster, such as a tornado, flood, or wildfire. An evacuation plan can help the community more effectively respond to an emergency, and so could help save lives. However, it can be difficult for a city to evaluate such a plan because it is not practical to have an entire town or city rehearse a full blown evacuation. For example, Mill Valley, a city in northern California, created a wildfire evacuation plan but lacked an estimate for how long the evacuation would take.

Today we describe a case study in which we teamed up with the city of Mill Valley to test and improve their evacuation plan. We outline our approach in our paper, “Mill Valley Evacuation Study”. We started by using a traffic simulator to model a citywide evacuation. The research goal was to provide the city with detailed estimates for how long it would take to evacuate the city, and, by studying the egress pattern, to find modifications to make the plan more effective. While our prior work on this subject provided an estimate for the evacuation time and showed how the time could be reduced if certain road changes were implemented, it turns out the recommendations in that paper — such as changing the number of outgoing lanes on an arterial — were not feasible. The current round of research improves upon the initial study by more accurately modeling the number and starting locations of vehicles, by using a more realistic map, and by working closely with city officials to ensure that recommended changes to the plan are deemed viable.

Geography and methodology

Mill Valley is in Marin County, California, north of San Francisco. Many of the residences are located on the steep hillsides of several valleys surrounded by dense redwood forests.

|

|

| Aerial views of Mill Valley, courtesy of the City of Mill Valley. |

Many of those residences are in areas that have only one exit direction, toward the town center. From there the best evacuation route is toward Highway 101, which is in the flat part of the city and is the most likely area to be far from potential wildfires. Some neighborhoods have other routes that lead away from both the city and Highway 101, but those routes pass through hilly forested areas, which could be dangerous or impassable during a wildfire. So, the evacuation plan directs all vehicles west of Highway 101 to head east, to the highway (see map below). The neighborhoods east of Highway 101 are not included in the simulation because they are away from areas with a high fire hazard rating, and are close to the highway.

Mill Valley has about 11,400 households west of Highway 101. Most Mill Valley households have two vehicles. Evacuation times scale with the number of vehicles, so it is in the common interest to minimize the number of vehicles used during an evacuation. To that end, Mill Valley has a public awareness campaign aimed at having each household evacuate in one vehicle. While no one knows how many vehicles would be used during an evacuation, it is safe to assume it is on average between one and two per household. The basic evacuation problem, then, is how to efficiently get between 11 and 23 thousand vehicles from the various residences onto one of the three sets of Highway 101 on-ramps.

The current work uses the same general methodology as the previous research, namely, running the open source SUMO agent-based traffic simulator on a map of Mill Valley. The traffic simulator models traffic by simulating each vehicle individually. The detailed behaviors of vehicles are dictated by a car-following model. Each vehicle is given a point and time at which to start and an initial route. The routes of most vehicles are updated throughout the simulation, depending on conditions. To consider potential changes in driver behavior under the high stress conditions of an evacuation, the effects of the “aggressiveness” of each car is also investigated, but in our case the impacts are minimal. Some simplifying assumptions are that vehicles originate at residential addresses and the roads and highways are initially empty. These assumptions correspond approximately to conditions that could be encountered if an evacuation happens in the middle of the night. The main inputs in the simulation are the road network, the household locations, the average number of vehicles per household, and a departure temporal distribution. We have to make assumptions about the departure distribution. After discussing with the city officials, we chose a distribution such that most vehicles depart within an hour.

Four bottlenecks

Mill Valley has three sets of Highway 101 on-ramps: northern, middle, and southern. All the vehicles must use one of these sets of on-ramps to reach their destination (either the northernmost or southernmost segment of Highway 101 included in our map). Given that we are only concerned with the majority of Mill Valley that lies west of the highway, there are two lanes that approach the northern on-ramps, and one lane that approaches each of the middle and southern on-ramps. Since every vehicle has to pass over one of these four lanes to reach the highway, they are the bottlenecks. Given the geography and existing infrastructure, adding more lanes is infeasible. The aim of this research, then, is to try to modify traffic patterns to maximize the rate of traffic on each of the four lanes.

Evacuation plan

When we started this research, Mill Valley had a preliminary evacuation plan. It included modifying traffic patterns — disabling traffic lights and changing traffic rules — on a few road segments, as well as specifying the resources (traffic officers, signage) necessary to implement the changes. As an example, a two-way road may be changed to a one-way road to double the number of outgoing lanes. Temporarily changing the direction of traffic is called contraflow.

The plot below shows the simulated fraction of vehicles that have departed or reached their destinations versus time, for 1, 1.5, and 2 vehicles per household (left to right). The dashed line on the far left shows the fraction that have departed. The solid black lines show the preliminary evacuation plan results and the dotted lines indicate the normal road network (baseline) results. The preliminary evacuation plan significantly speeds up the evacuation.

We can understand how effective the preliminary evacuation plan is by measuring the rates at the bottlenecks. The below plots show the rate of traffic on each of the four lanes leading to the highway on-ramps for the case of 1.5 vehicles per household for both the baseline case (the normal road rules; shown shaded in gray) and the preliminary evacuation plan (shown outlined in black). The average rate per lane varies greatly in the different cases. It is clear that, while the evacuation plan leads to increased evacuation rates, there is room for improvement. In particular, the middle on-ramps are quite underutilized.

Final evacuation plan

After studying the map and investigating different alternatives, we, working together with city officials, found a minimal set of new road changes that substantially lower the evacuation time compared to the preliminary evacuation plan (shown below). We call this the final evacuation plan. It extends the contraflow section of the preliminary plan 1000 feet further west, to a main intersection. Crucially, this allows for one of the (normally) two outgoing lanes to be dedicated to routing traffic to the middle on-ramps. It also creates two outgoing lanes from that main intersection clear through to the northern on-ramps, over ¾ of a mile to the east.

The rate per lane plots comparing the preliminary and final evacuation plans are shown below for 1.5 vehicles per household. The simulation indicates that the final plan increases the average rate of traffic on the lane leading to the middle on-ramps from about 4 vehicles per minute to about 18. It also increases the through rate of the northern on-ramps by over 60%.

|

| The rates of traffic on the four lanes leading to Highway 101 on-ramps for both the preliminary case (shown shaded in gray) and the final evacuation plan (shown outlined in black). |

The below plot shows the cumulative fraction of vehicles vs. time, comparing the cases of 1, 1.5 and 2 vehicles per household for the preliminary and final evacuation plans. The speedup is quite significant, on the scale of hours. For example, with 1.5 vehicles per household, it took 5.3 hours to evacuate the city using the preliminary evacuation plan, and only 3.5 hours using the final plan.

Conclusion

Evacuation plans can be crucial in quickly getting many people to safety in emergency situations. While some cities have traffic evacuation plans in place, it can be difficult for officials to learn how well the plan works or whether it can be improved. Google Research helped Mill Valley test and evaluate their evacuation plan by running traffic simulations. We found that, while the preliminary plan did speed up the evacuation time, some minor changes to the plan significantly expedited evacuation. We worked closely with the city during this research, and Mill Valley has adopted the final plan. We were able to provide the city with more simulation details, including results for evacuating the city one area at a time. Full details can be found in the paper.

Detailed recommendations for a particular evacuation plan are necessarily specific to the area under study. So, the specific road network changes we found for Mill Valley are not directly applicable for other cities. However, we used only public data (road network from OpenStreetMap; household information from census data) and an open source simulator (SUMO), so any city or agency could use the methodology used in our paper to obtain results for their area.

Acknowledgements

We thank former Mayor John McCauley and City of Mill Valley personnel Tom Welch, Lindsay Haynes, Danielle Staude, Rick Navarro and Alan Piombo for numerous discussions and feedback, and Carla Bromberg for program management.

Calling all AI cybersecurity startups — in Europe and, now, the U.S.

Launch of the new Google for Startups Growth Academy: AI for Cybersecurity program for companies based in Europe and the U.S.Read More

Launch of the new Google for Startups Growth Academy: AI for Cybersecurity program for companies based in Europe and the U.S.Read More

Batch calibration: Rethinking calibration for in-context learning and prompt engineering

Prompting large language models (LLMs) has become an efficient learning paradigm for adapting LLMs to a new task by conditioning on human-designed instructions. The remarkable in-context learning (ICL) ability of LLMs also leads to efficient few-shot learners that can generalize from few-shot input-label pairs. However, the predictions of LLMs are highly sensitive and even biased to the choice of templates, label spaces (such as yes/no, true/false, correct/incorrect), and demonstration examples, resulting in unexpected performance degradation and barriers for pursuing robust LLM applications. To address this problem, calibration methods have been developed to mitigate the effects of these biases while recovering LLM performance. Though multiple calibration solutions have been provided (e.g., contextual calibration and domain-context calibration), the field currently lacks a unified analysis that systematically distinguishes and explains the unique characteristics, merits, and downsides of each approach.

With this in mind, in “Batch Calibration: Rethinking Calibration for In-Context Learning and Prompt Engineering”, we conduct a systematic analysis of the existing calibration methods, where we both provide a unified view and reveal the failure cases. Inspired by these analyses, we propose Batch Calibration (BC), a simple yet intuitive method that mitigates the bias from a batch of inputs, unifies various prior approaches, and effectively addresses the limitations in previous methods. BC is zero-shot, self-adaptive (i.e., inference-only), and incurs negligible additional costs. We validate the effectiveness of BC with PaLM 2 and CLIP models and demonstrate state-of-the-art performance over previous calibration baselines across more than 10 natural language understanding and image classification tasks.

Motivation

In pursuit of practical guidelines for ICL calibration, we started with understanding the limitations of current methods. We find that the calibration problem can be framed as an unsupervised decision boundary learning problem. We observe that uncalibrated ICL can be biased towards predicting a class, which we explicitly refer to as contextual bias, the a priori propensity of LLMs to predict certain classes over others unfairly given the context. For example, the prediction of LLMs can be biased towards predicting the most frequent label, or the label towards the end of the demonstration. We find that, while theoretically more flexible, non-linear boundaries (prototypical calibration) tend to be susceptible to overfitting and may suffer from instability for challenging multi-class tasks. Conversely, we find that linear decision boundaries can be more robust and generalizable across tasks. In addition, we find that relying on additional content-free inputs (e.g., “N/A” or random in-domain tokens) as the grounds for estimating the contextual bias is not always optimal and may even introduce additional bias, depending on the task type.

Batch calibration

Inspired by the previous discussions, we designed BC to be a zero-shot, inference-only and generalizable calibration technique with negligible computation cost. We argue that the most critical component for calibration is to accurately estimate the contextual bias. We, therefore, opt for a linear decision boundary for its robustness, and instead of relying on content-free inputs, we propose to estimate the contextual bias for each class from a batch in a content-based manner by marginalizing the output score over all samples within the batch, which is equivalent to measuring the mean score for each class (visualized below).

We then obtain the calibrated probability by dividing the output probability over the contextual prior, which is equivalent to aligning the log-probability (LLM scores) distribution to the estimated mean of each class. It is noteworthy that because it requires no additional inputs to estimate the bias, this BC procedure is zero-shot, only involves unlabeled test samples, and incurs negligible computation costs. We may either compute the contextual bias once all test samples are seen, or alternatively, in an on-the-fly manner that dynamically processes the outputs. To do so, we may use a running estimate of the contextual bias for BC, thereby allowing BC’s calibration term to be estimated from a small number of mini-batches that is subsequently stabilized when more mini-batches arrive.

Experiment design

For natural language tasks, we conduct experiments on 13 more diverse and challenging classification tasks, including the standard GLUE and SuperGLUE datasets. This is in contrast to previous works that only report on relatively simple single-sentence classification tasks.. For image classification tasks, we include SVHN, EuroSAT, and CLEVR. We conduct experiments mainly on the state-of-the-art PaLM 2 with size variants PaLM 2-S, PaLM 2-M, and PaLM 2-L. For VLMs, we report the results on CLIP ViT-B/16.

Results

Notably, BC consistently outperforms ICL, yielding a significant performance enhancement of 8% and 6% on small and large variants of PaLM 2, respectively. This shows that the BC implementation successfully mitigates the contextual bias from the in-context examples and unleashes the full potential of LLM in efficient learning and quick adaptation to new tasks. In addition, BC improves over the state-of-the-art prototypical calibration (PC) baseline by 6% on PaLM 2-S, and surpasses the competitive contextual calibration (CC) baseline by another 3% on average on PaLM 2-L. Specifically, BC is a generalizable and cheaper technique across all evaluated tasks, delivering stable performance improvement, whereas previous baselines exhibit varying degrees of performance across tasks.

|

| Batch Calibration (BC) achieves the best performance on 1-shot ICL over calibration baselines: contextual calibration (CC), domain-context calibration (DC), and prototypical calibration (PC) on an average of 13 NLP tasks on PaLM 2 and outperforms the zero-shot CLIP on image tasks. |

We analyze the performance of BC by varying the number of ICL shots from 0 to 4, and BC again outperforms all baseline methods. We also observe an overall trend for improved performance when more shots are available, where BC demonstrates the best stability.

|

| The ICL performance on various calibration techniques over the number of ICL shots on PaLM 2-S. We compare BC with the uncalibrated ICL, contextual calibration (CC), domain-context calibration (DC), and prototypical calibration (PC) baselines. |

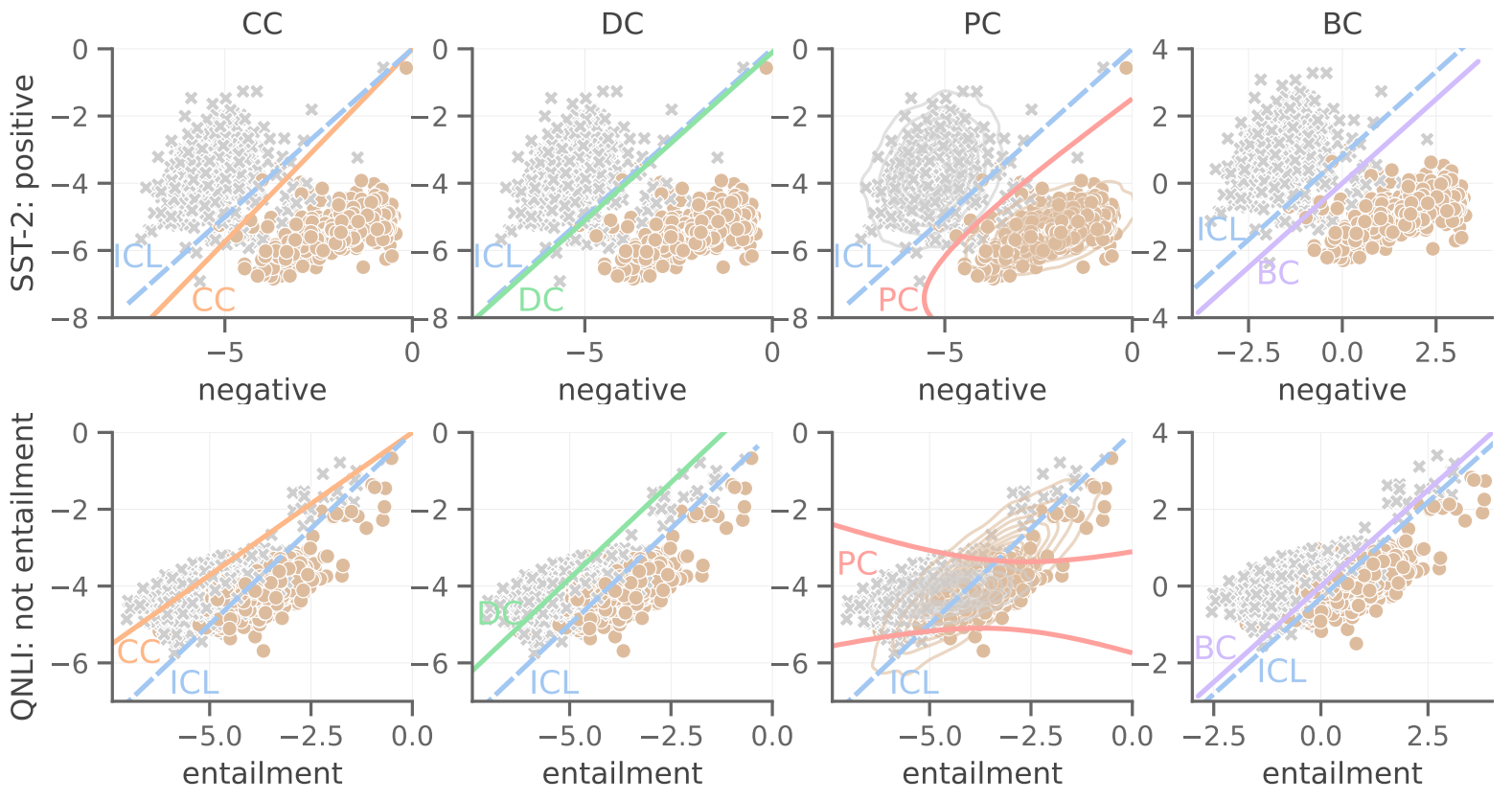

We further visualize the decision boundaries of uncalibrated ICL after applying existing calibration methods and the proposed BC. We show success and failure cases for each baseline method, whereas BC is consistently effective.

|

| Visualization of the decision boundaries of uncalibrated ICL, and after applying existing calibration methods and the proposed BC in representative binary classification tasks of SST-2 (top row) and QNLI (bottom row) on 1-shot PaLM 2-S. Each axis indicates the LLM score on the defined label. |

Robustness and ablation studies

We analyze the robustness of BC with respect to common prompt engineering design choices that were previously shown to significantly affect LLM performance: choices and orders of in-context examples, the prompt template for ICL, and the label space. First, we find that BC is more robust to ICL choices and can mostly achieve the same performance with different ICL examples. Additionally, given a single set of ICL shots, altering the order between each ICL example has minimal impact on the BC performance. Furthermore, we analyze the robustness of BC under 10 designs of prompt templates, where BC shows consistent improvement over the ICL baseline. Therefore, though BC improves performance, a well-designed template can further enhance the performance of BC. Lastly, we examine the robustness of BC to variations in label space designs (see appendix in our paper). Remarkably, even when employing unconventional choices such as emoji pairs as labels, leading to dramatic oscillations of ICL performance, BC largely recovers performance. This observation demonstrates that BC increases the robustness of LLM predictions under common prompt design choices and makes prompt engineering easier.

|

| Batch Calibration makes prompt engineering easier while being data-efficient. Data are visualized as a standard box plot, which illustrates values for the median, first and third quartiles, and minimum and maximum. |

Moreover, we study the impact of batch size on the performance of BC. In contrast to PC, which also leverages an unlabeled estimate set, BC is remarkably more sample efficient, achieving a strong performance with only around 10 unlabeled samples, whereas PC requires more than 500 unlabeled samples before its performance stabilizes.

|

| Batch Calibration makes prompt engineering easier while being insensitive to the batch size. |

Conclusion

We first revisit previous calibration methods while addressing two critical research questions from an interpretation of decision boundaries, revealing their failure cases and deficiencies. We then propose Batch Calibration, a zero-shot and inference-only calibration technique. While methodologically simple and easy to implement with negligible computation cost, we show that BC scales from a language-only setup to the vision-language context, achieving state-of-the-art performance in both modalities. BC significantly improves the robustness of LLMs with respect to prompt designs, and we expect easy prompt engineering with BC.

Acknowledgements

This work was conducted by Han Zhou, Xingchen Wan, Lev Proleev, Diana Mincu, Jilin Chen, Katherine Heller, Subhrajit Roy. We would like to thank Mohammad Havaei and other colleagues at Google Research for their discussion and feedback.

Developing industrial use cases for physical simulation on future error-corrected quantum computers

If you’ve paid attention to the quantum computing space, you’ve heard the claim that in the future, quantum computers will solve certain problems exponentially more efficiently than classical computers can. They have the potential to transform many industries, from pharmaceuticals to energy.

For the most part, these claims have rested on arguments about the asymptotic scaling of algorithms as the problem size approaches infinity, but this tells us very little about the practical performance of quantum computers for finite-sized problems. We want to be more concrete: Exactly which problems are quantum computers more suited to tackle than their classical counterparts, and exactly what quantum algorithms could we run to solve these problems? Once we’ve designed an algorithm, we can go beyond analysis based on asymptotic scaling — we can determine the actual resources required to compile and run the algorithm on a quantum computer, and how that compares to a classical computation.

Over the last few years, Google Quantum AI has collaborated with industry and academic partners to assess the prospects for quantum simulation to revolutionize specific technologies and perform concrete analyses of the resource requirements. In 2022, we developed quantum algorithms to analyze the chemistry of an important enzyme family called cytochrome P450. Then, in our paper released this fall, we demonstrated how to use a quantum computer to study sustainable alternatives to cobalt for use in lithium ion batteries. And most recently, as we report in a preprint titled “Quantum computation of stopping power for inertial fusion target design,” we’ve found a new application in modeling the properties of materials in inertial confinement fusion experiments, such as those at the National Ignition Facility (NIF) at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, which recently made headlines for a breakthrough in nuclear fusion.

Below, we describe these three industrially relevant applications for simulations with quantum computers. While running the algorithms will require an error-corrected quantum computer, which is still years away, working on this now will ensure that we are ready with efficient quantum algorithms when such a quantum computer is built. Already, our work has reduced the cost of compiling and running the algorithms significantly, as we have reported in the past. Our work is essential for demonstrating the potential of quantum computing, but it also provides our hardware team with target specifications for the number of qubits and time needed to run useful quantum algorithms in the future.

Application 1: The CYP450 mechanism

The pharmaceutical industry is often touted as a field ripe for discovery using quantum computers. But concrete examples of such potential applications are few and far between. Working with collaborators at the pharmaceutical company Boehringer Ingelheim, our partners at the startup QSimulate, and academic colleagues at Columbia University, we explored one example in the 2022 PNAS article, “Reliably assessing the electronic structure of cytochrome P450 on today’s classical computers and tomorrow’s quantum computers”.

Cytochrome P450 is an enzyme family naturally found in humans that helps us metabolize drugs. It excels at its job: more than 70% of all drug metabolism is performed by enzymes of the P450 family. The enzymes work by oxidizing the drug — a process that depends on complex correlations between electrons. The details of the interactions are too complicated for scientists to know a priori how effective the enzyme will be on a particular drug.

In the paper, we showed how a quantum computer could approach this problem. The CYP450 metabolic process is a complex chain of reactions with many intermediate changes in the electronic structure of the enzymes throughout. We first use state-of-the-art classical methods to determine the resources required to simulate this problem on a classical computer. Then we imagine implementing a phase-estimation algorithm — which is needed to compute the ground-state energies of the relevant electronic configurations throughout the reaction chain — on a surface-code error-corrected quantum computer.

With a quantum computer, we could follow the chain of changing electronic structure with greater accuracy and fewer resources. In fact, we find that the higher accuracy offered by a quantum computer is needed to correctly resolve the chemistry in this system, so not only will a quantum computer be better, it will be necessary. And as the system size gets bigger, i.e., the more quantum energy levels we include in the simulation, the more the quantum computer wins over the classical computer. Ultimately, we show that a few million physical qubits would be required to reach quantum advantage for this problem.

Application 2: Lithium-ion batteries

Lithium-ion batteries rely on the electrochemical potential difference between two lithium containing materials. One material used today for the cathodes of Li-ion batteries is LiCoO2. Unfortunately, it has drawbacks from a manufacturing perspective. Cobalt mining is expensive, destructive to the environment, and often utilizes unsafe or abusive labor practices. Consequently, many in the field are interested in alternatives to cobalt for lithium-ion cathodes.

In the 1990’s, researchers discovered that nickel could replace cobalt to form LiNiO2 (called “lithium nickel oxide” or “LNO”) for cathodes. While pure LNO was found to be unstable in production, many cathode materials used in the automotive industry today use a high fraction of nickel and hence, resemble LNO. Despite its applications to industry, however, not all of the chemical properties of LNO are understood — even the properties of its ground state remains a subject of debate.

In our recent paper, “Fault tolerant quantum simulation of materials using Bloch orbitals,” we worked with the chemical company, BASF, the molecular modeling startup, QSimulate, and collaborators at Macquarie University in Australia to develop techniques to perform quantum simulations on systems with periodic, regularly spaced atomic structure, such as LNO. We then applied these techniques to design algorithms to study the relative energies of a few different candidate structures of LNO. With classical computers, high accuracy simulations of the quantum wavefunction are considered too expensive to perform. In our work, we found that a quantum computer would need tens of millions of physical qubits to calculate the energies of each of the four candidate ground-state LNO structures. This is out of reach of the first error-corrected quantum computers, but we expect this number to come down with future algorithmic improvements.

|

| Four candidate structures of LNO. In the paper, we consider the resources required to compare the energies of these structures in order to find the ground state of LNO. |

Application 3: Fusion reactor dynamics

In our third and most recent example, we collaborated with theorists at Sandia National Laboratories and our Macquarie University collaborators to put our hypothetical quantum computer to the task of simulating dynamics of charged particles in the extreme conditions typical of inertial confinement fusion (ICF) experiments, like those at the National Ignition Facility. In those experiments, high-intensity lasers are focused into a metallic cavity (hohlraum) that holds a target capsule consisting of an ablator surrounding deuterium–tritium fuel. When the lasers heat the inside of the hohlraum, its walls radiate x-rays that compress the capsule, heating the deuterium and tritium inside to 10s of millions of Kelvin. This allows the nucleons in the fuel to overcome their mutual electrostatic repulsion and start fusing into helium nuclei, also called alpha particles.

Simulations of these experiments are computationally demanding and rely on models of material properties that are themselves uncertain. Even testing these models, using methods similar to those in quantum chemistry, is extremely computationally expensive. In some cases, such test calculations have consumed >100 million CPU hours. One of the most expensive and least accurate aspects of the simulation is the dynamics of the plasma prior to the sustained fusion stage (>10s of millions of Kelvin), when parts of the capsule and fuel are a more balmy 100k Kelvin. In this “warm dense matter” regime, quantum correlations play a larger role in the behavior of the system than in the “hot dense matter” regime when sustained fusion takes place.

In our new preprint, “Quantum computation of stopping power for inertial fusion target design”, we present a quantum algorithm to compute the so-called “stopping power” of the warm dense matter in a nuclear fusion experiment. The stopping power is the rate at which a high energy alpha particle slows down due to Coulomb interactions with the surrounding plasma. Understanding the stopping power of the system is vital for optimizing the efficiency of the reactor. As the alpha particle is slowed by the plasma around it, it transfers its energy to the plasma, heating it up. This self-heating process is the mechanism by which fusion reactions sustain the burning plasma. Detailed modeling of this process will help inform future reactor designs.

We estimate that the quantum algorithm needed to calculate the stopping power would require resources somewhere between the P450 application and the battery application. But since this is the first case study on first-principles dynamics (or any application at finite temperature), such estimates are just a starting point and we again expect to find algorithmic improvements to bring this cost down in the future. Despite this uncertainty, it is still certainly better than the classical alternative, for which the only tractable approaches for these simulations are mean-field methods. While these methods incur unknown systematic errors when describing the physics of these systems, they are currently the only meaningful means of performing such simulations.

Discussion and conclusion

The examples described above are just three of a large and growing body of concrete applications for a future error-corrected quantum computer in simulating physical systems. This line of research helps us understand the classes of problems that will most benefit from the power of quantum computing. In particular, the last example is distinct from the other two in that it is simulating a dynamical system. In contrast to the other problems, which focus on finding the lowest energy, static ground state of a quantum system, quantum dynamics is concerned with how a quantum system changes over time. Since quantum computers are inherently dynamic — the qubit states evolve and change as each operation is performed — they are particularly well suited to solving these kinds of problems. Together with collaborators at Columbia, Harvard, Sandia National Laboratories and Macquarie University in Australia we recently published a paper in Nature Communications demonstrating that quantum algorithms for simulating electron dynamics can be more efficient even than approximate, “mean-field” classical calculations, while simultaneously offering much higher accuracy.

Developing and improving algorithms today prepares us to take full advantage of them when an error-corrected quantum computer is eventually realized. Just as in the classical computing case, we expect improvements at every level of the quantum computing stack to further lower the resource requirements. But this first step helps separate hyperbole from genuine applications amenable to quantum computational speedups.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Katie McCormick, our Quantum Science Communicator, for helping to write this blog post.

Our responsible approach to building guardrails for generative AI

We’re sharing some of the ways we’re building guardrails for generative AI.Read More

New ways to get inspired with generative AI in Search

We’re testing new ways to get started on something you need to do — like creating an image that can bring an idea to life, or a written draft when you need a starting po…Read More

We’re testing new ways to get started on something you need to do — like creating an image that can bring an idea to life, or a written draft when you need a starting po…Read More

New ways we’re helping reduce transportation and energy emissions

These new product features and expansions help people, city planners and policy makers take action toward building a sustainable future.Read More

These new product features and expansions help people, city planners and policy makers take action toward building a sustainable future.Read More

Demand more from social with AI-powered ads

Learn how Demand Gen campaigns can help you drive better results across YouTube and Google. See new case studies, videos, tips, and more.Read More

Learn how Demand Gen campaigns can help you drive better results across YouTube and Google. See new case studies, videos, tips, and more.Read More

SANPO: A Scene understanding, Accessibility, Navigation, Pathfinding, & Obstacle avoidance dataset

As most people navigate their everyday world, they process visual input from the environment using an eye-level perspective. Unlike robots and self-driving cars, people don’t have any “out-of-body” sensors to help guide them. Instead, a person’s sensory input is completely “egocentric”, or “from the self.” This also applies to new technologies that understand the world around us from a human-like perspective, e.g., robots navigating through unknown buildings, AR glasses that highlight objects, or assistive technology to help people run independently.

In computer vision, scene understanding is the subfield that studies how visible objects relate to the scene’s 3D structure and layout by focusing on the spatial, functional, and semantic relationships between objects and their environment. For example, autonomous drivers must understand the 3D structure of the road, sidewalks, and surrounding buildings while identifying and recognizing street signs and stop lights, a task made easier with 3D data from a special laser scanner mounted on the top of the car rather than 2D images from the driver’s perspective. Robots navigating a park must understand where the path is and what obstacles might interfere, which is simplified with a map of their surroundings and GPS positioning data. Finally, AR glasses that help users find their way need to understand where the user is and what they are looking at.

The computer vision community typically studies scene understanding tasks in contexts like self-driving, where many other sensors (GPS, wheel positioning, maps, etc.) beyond egocentric imagery are available. Yet most datasets in this space do not focus exclusively on egocentric data, so they are less applicable to human-centered navigation tasks. While there are plenty of self-driving focused scene understanding datasets, they have limited generalization to egocentric human scene understanding. A comprehensive human egocentric dataset would help build systems for related applications and serve as a challenging benchmark for the scene understanding community.

To that end, we present the Scene understanding, Accessibility, Navigation, Pathfinding, Obstacle avoidance dataset, or SANPO (also the Japanese word for ”brisk stroll”), a multi-attribute video dataset for outdoor human egocentric scene understanding. The dataset consists of real world data and synthetic data, which we call SANPO-Real and SANPO-Synthetic, respectively. It supports a wide variety of dense prediction tasks, is challenging for current models, and includes real and synthetic data with depth maps and video panoptic masks in which each pixel is assigned a semantic class label (and for some semantic classes, each pixel is also assigned a semantic instance ID that uniquely identifies that object in the scene). The real dataset covers diverse environments and has videos from two stereo cameras to support multi-view methods, including 11.4 hours captured at 15 frames per second (FPS) with dense annotations. Researchers can download and use SANPO here.

SANPO-Real

SANPO-Real is a multiview video dataset containing 701 sessions recorded with two stereo cameras: a head-mounted ZED Mini and a chest-mounted ZED-2i. That’s four RGB streams per session at 15 FPS. 597 sessions are recorded at a resolution of 2208×1242 pixels, and the remainder are recorded at a resolution of 1920×1080 pixels. Each session is approximately 30 seconds long, and the recorded videos are rectified using Zed software and saved in a lossless format. Each session has high-level attribute annotations, camera pose trajectories, dense depth maps from CREStereo, and sparse depth maps provided by the Zed SDK. A subset of sessions have temporally consistent panoptic segmentation annotations of each instance.

Temporally consistent panoptic segmentation annotation protocol

SANPO includes thirty different class labels, including various surfaces (road, sidewalk, curb, etc.), fences (guard rails, walls,, gates), obstacles (poles, bike racks, trees), and creatures (pedestrians, riders, animals). Gathering high-quality annotations for these classes is an enormous challenge. To provide temporally consistent panoptic segmentation annotation we divide each video into 30-second sub-videos and annotate every fifth frame (90 frames per sub-video), using a cascaded annotation protocol. At each stage, we ask annotators to draw borders around five mutually exclusive labels at a time. We send the same image to different annotators with as many stages as it takes to collect masks until all labels are assigned, with annotations from previous subsets frozen and shown to the annotator. We use AOT, a machine learning model that reduces annotation effort by giving annotators automatic masks from which to start, taken from previous frames during the annotation process. AOT also infers segmentation annotations for intermediate frames using the manually annotated preceding and following frames. Overall, this approach reduces annotation time, improves boundary precision, and ensures temporally consistent annotations for up to 30 seconds.

|

| Temporally consistent panoptic segmentation annotations. The segmentation mask’s title indicates whether it was manually annotated or AOT propagated. |

SANPO-Synthetic

Real-world data has imperfect ground truth labels due to hardware, algorithms, and human mistakes, whereas synthetic data has near-perfect ground truth and can be customized. We partnered with Parallel Domain, a company specializing in lifelike synthetic data generation, to create SANPO-Synthetic, a high-quality synthetic dataset to supplement SANPO-Real. Parallel Domain is skilled at creating handcrafted synthetic environments and data for machine learning applications. Thanks to their work, SANPO-Synthetic matches real-world capture conditions with camera parameters, placement, and scenery.

SANPO-Synthetic is a high quality video dataset, handcrafted to match real world scenarios. It contains 1961 sessions recorded using virtualized Zed cameras, evenly split between chest-mounted and head-mounted positions and calibrations. These videos are monocular, recorded from the left lens only. These sessions vary in length and FPS (5, 14.28, and 33.33) for a mix of temporal resolution / length tradeoffs, and are saved in a lossless format. All the sessions have precise camera pose trajectories, dense pixel accurate depth maps and temporally consistent panoptic segmentation masks.

SANPO-Synthetic data has pixel-perfect annotations, even for small and distant instances. This helps develop challenging datasets that mimic the complexity of real-world scenes. SANPO-Synthetic and SANPO-Real are also drop-in replacements for each other, so researchers can study domain transfer tasks or use synthetic data during training with few domain-specific assumptions.

|

| An even sampling of real and synthetic scenes. |

Statistics

Semantic classes

We designed our SANPO taxonomy: i) with human egocentric navigation in mind, ii) with the goal of being reasonably easy to annotate, and iii) to be as close as possible to the existing segmentation taxonomies. Though built with human egocentric navigation in mind, it can be easily mapped or extended to other human egocentric scene understanding applications. Both SANPO-Real and SANPO-Synthetic feature a wide variety of objects one would expect in egocentric obstacle detection data, such as roads, buildings, fences, and trees. SANPO-Synthetic includes a broad distribution of hand-modeled objects, while SANPO-Real features more “long-tailed” classes that appear infrequently in images, such as gates, bus stops, or animals.

|

| Distribution of images across the classes in the SANPO taxonomy. |

Instance masks

SANPO-Synthetic and a portion of SANPO-Real are also annotated with panoptic instance masks, which assign each pixel to a class and instance ID. Because it is generally human-labeled, SANPO-Real has a large number of frames with generally less than 20 instances per frame. Similarly, SANPO-Synthetic’s virtual environment offers pixel-accurate segmentation of most unique objects in the scene. This means that synthetic images frequently feature many more instances within each frame.

|

| When considering per-frame instance counts, synthetic data frequently features many more instances per frame than the labeled portions of SANPO-Real. |

Comparison to other datasets

We compare SANPO to other important video datasets in this field, including SCAND, MuSoHu, Ego4D, VIPSeg, and Waymo Open. Some of these are intended for robot navigation (SCAND) or autonomous driving (Waymo) tasks. Across these datasets, only Waymo Open and SANPO have both panoptic segmentations and depth maps, and only SANPO has both real and synthetic data.

Conclusion and future work

We present SANPO, a large-scale and challenging video dataset for human egocentric scene understanding, which includes real and synthetic samples with dense prediction annotations. We hope SANPO will help researchers build visual navigation systems for the visually impaired and advance visual scene understanding. Additional details are available in the preprint and on the SANPO dataset GitHub repository.

Acknowledgements

This dataset was the outcome of hard work of many individuals from various teams within Google and our external partner, Parallel Domain.

Core Team: Mikhail Sirotenko, Dave Hawkey, Sagar Waghmare, Kimberly Wilber, Xuan Yang, Matthew Wilson

Parallel Domain: Stuart Park, Alan Doucet, Alex Valence-Lanoue, & Lars Pandikow.

We would also like to thank following team members: Hartwig Adam, Huisheng Wang, Lucian Ionita, Nitesh Bharadwaj, Suqi Liu, Stephanie Debats, Cattalyya Nuengsigkapian, Astuti Sharma, Alina Kuznetsova, Stefano Pellegrini, Yiwen Luo, Lily Pagan, Maxine Deines, Alex Siegman, Maura O’Brien, Rachel Stigler, Bobby Tran, Supinder Tohra, Umesh Vashisht, Sudhindra Kopalle, Reet Bhatia.