In this blog, we discuss the methods we used to achieve FP16 inference with popular LLM models such as Meta’s Llama3-8B and IBM’s Granite-8B Code, where 100% of the computation is performed using OpenAI’s Triton Language.

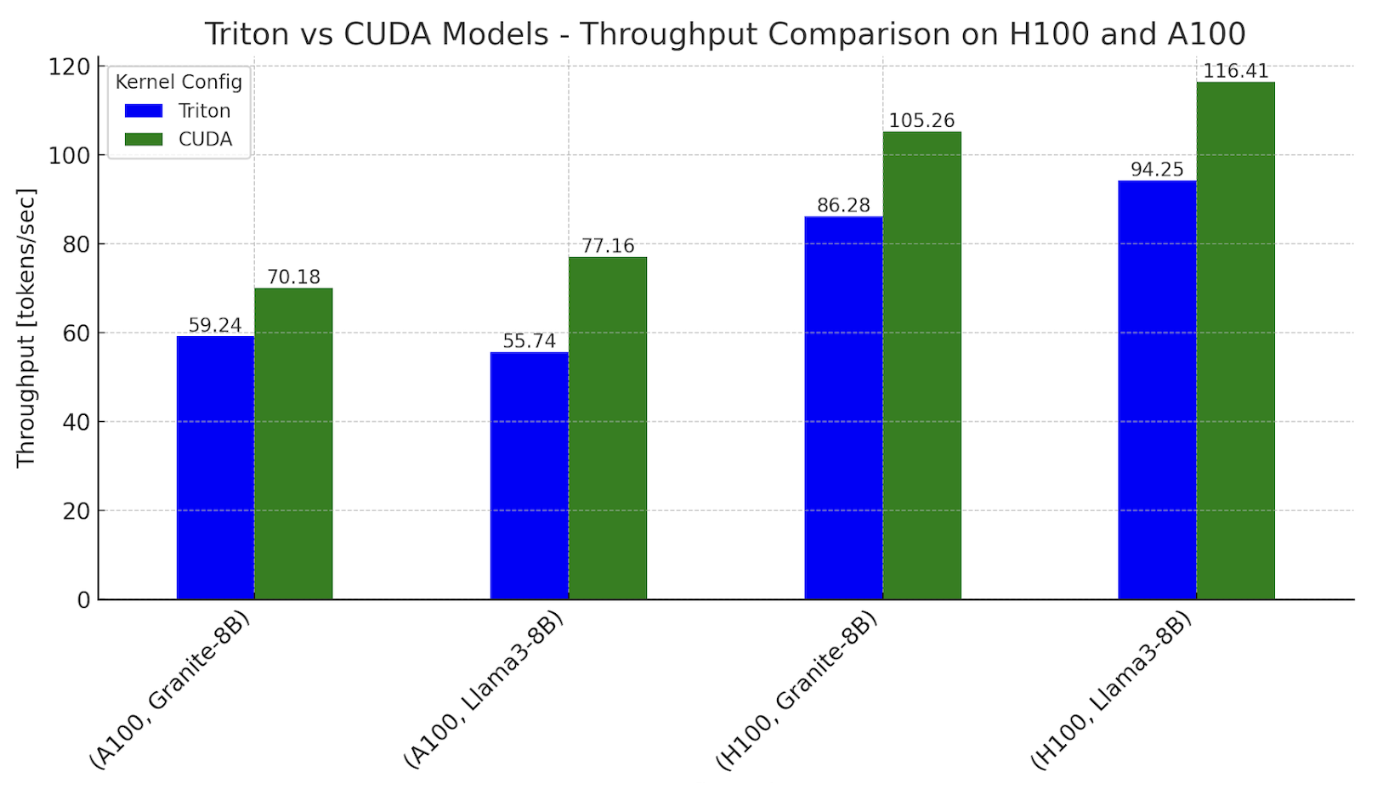

For single token generation times using our Triton kernel based models, we were able to approach 0.76-0.78x performance relative to the CUDA kernel dominant workflows for both Llama and Granite on Nvidia H100 GPUs, and 0.62-0.82x on Nvidia A100 GPUs.

Why explore using 100% Triton? Triton provides a path for enabling LLMs to run on different types of GPUs – NVIDIA, AMD, and in the future Intel and other GPU based accelerators. It also provides a higher layer of abstraction in Python for programming GPUs and has allowed us to write performant kernels faster than authoring them using vendor specific APIs. In the rest of this blog, we will share how we achieve CUDA-free compute, micro-benchmark individual kernels for comparison, and discuss how we can further improve future Triton kernels to close the gaps.

Figure 1. Inference throughput benchmarks with Triton and CUDA variants of Llama3-8B and Granite-8B, on NVIDIA H100 and A100

Settings: batch size = 2, input sequence length = 512, output sequence length = 256

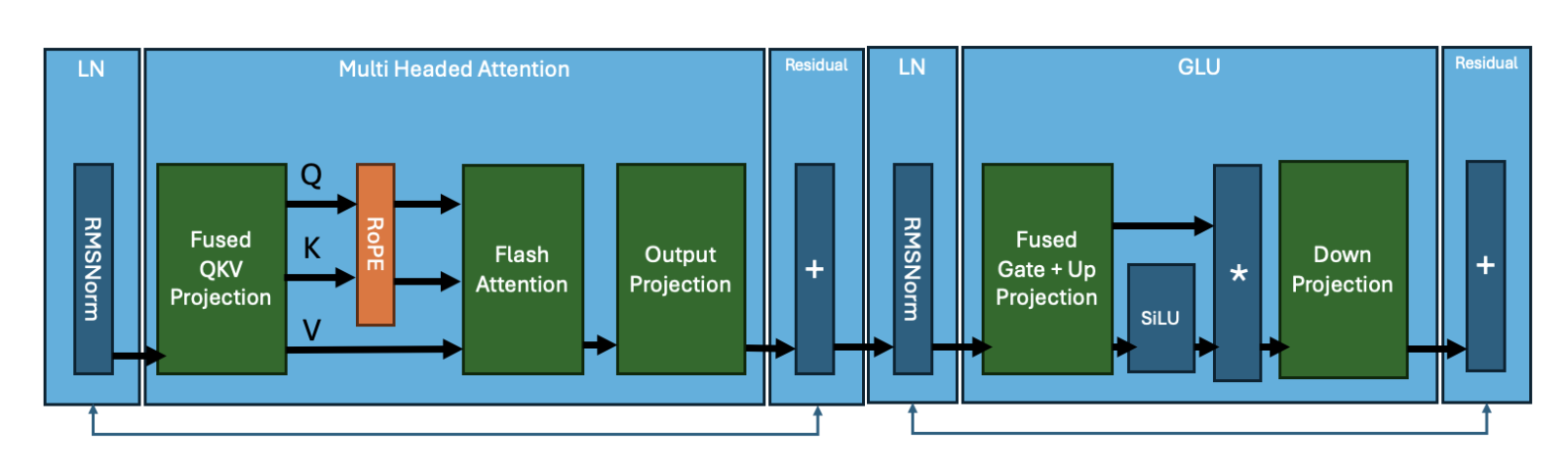

2.0 Composition of a Transformer Block

We start with a breakdown of the computations that happen in Transformer-based models. The figure below shows the “kernels” of a typical Transformer block.

Figure 2. Transformer Block by core kernels

Figure 2. Transformer Block by core kernels

The core operations for a Llama3 architecture are summarized in this list:

- RMSNorm

- Matrix multiplication: Fused QKV

- RoPE

- Attention

- Matrix multiplication: Output Projection

- RMSNorm

- Matrix multiplication: Fused Gate + Up Projection

- Activation function: SiLU

- Element Wise Multiplication

- Matrix multiplication: Down Projection

Each of these operations is computed on the GPU through the execution of one (or multiple) kernels. While the specifics of each of these kernels can vary across different transformer models, the core operations remain the same. For example, IBM’s Granite 8B Code model uses bias in the MLP layer, different from Llama3. Such changes do require modifications to the kernels. A typical model is a stack of these transformer blocks wired together with embedding layers.

3.0 Model Inference

Typical model architecture code is shared with a python model.py file that is launched by PyTorch. In the default PyTorch eager execution mode, these kernels are all executed with CUDA. To achieve 100% Triton for end-to-end Llama3-8B and Granite-8B inference we need to write and integrate handwritten Triton kernels as well as leverage torch.compile (to generate Triton ops). First, we replace smaller ops with compiler generated Triton kernels, and second, we replace more expensive and complex computations (e.g. matrix multiplication and flash attention) with handwritten Triton kernels.

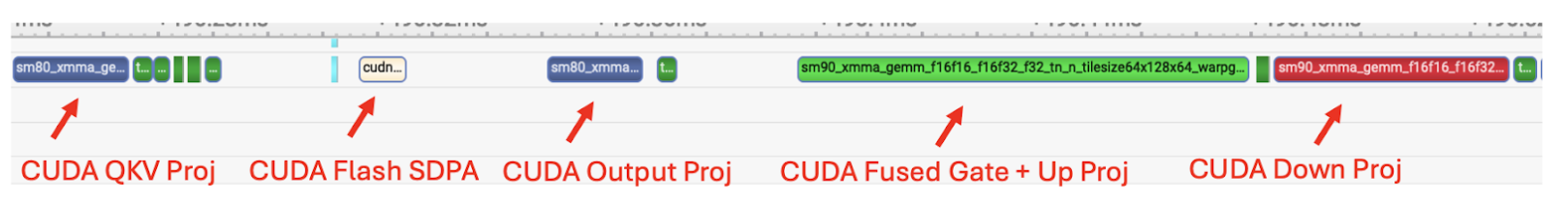

Torch.compile generates Triton kernels automatically for RMSNorm, RoPE, SiLU and Element Wise Multiplication. Using tools like Nsight Systems we can observe these generated kernels; they appear as tiny dark green kernels in-between the matrix multiplications and attention.

Figure 3. Trace of Llama3-8B with torch.compile, showing CUDA kernels being used for matrix multiplications and flash attention

Figure 3. Trace of Llama3-8B with torch.compile, showing CUDA kernels being used for matrix multiplications and flash attention

For the above trace, we note that the two major ops that make up 80% of the E2E latency in a Llama3-8B style model are matrix multiplication and attention kernels and both remain CUDA kernels. Thus to close the remaining gap, we replace both matmul and attention kernels with handwritten Triton kernels.

4.0 Triton SplitK GEMM Kernel

For the matrix multiplications in the linear layers, we wrote a custom FP16 Triton GEMM (General Matrix-Matrix Multiply) kernel that leverages a SplitK work decomposition. We have previously discussed this parallelization in other blogs as a way to accelerate the decoding portion of LLM inference.

5.0 GEMM Kernel Tuning

To achieve optimal performance we used the exhaustive search approach to tune our SplitK GEMM kernel. Granite-8B and Llama3-8B have linear layers with the following shapes:

| Linear Layer | Shape (in_features, out_features) |

|---|---|

| Fused QKV Projection | (4096, 6144) |

| Output Projection | (4096, 4096) |

| Fused Gate + Up Projection | (4096, 28672) |

| Down Projection | (14336, 4096) |

Figure 4. Granite-8B and Llama3-8B Linear Layer Weight Matrix Shapes

Each of these linear layers have different weight matrix shapes. Thus, for optimal performance the Triton kernel must be tuned for each of these shape profiles. After tuning for each linear layer we were able to achieve 1.20x E2E speedup on Llama3-8B and Granite-8B over the untuned Triton kernel.

6.0 Flash Attention Kernel

We evaluated a suite of existing Triton flash attention kernels with different configurations, namely:

We evaluated the text generation quality of each of these kernels, first, in eager mode and then (if we were able to torch.compile the kernel with standard methods) compile mode. For kernels 2-5, we noted the following:

| Kernel | Text Generation Quality | Torch.compile | Support for Arbitrary Sequence Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMD Flash | Coherent | Yes | Yes |

| OpenAI Flash | Incoherent | Did not evaluate. WIP to debug precision in eager mode first | No |

| Dao AI Lab Flash | Incoherent | Did not evaluate. WIP to debug precision in eager mode first | Yes |

| Xformers FlashDecoding | Hit a compilation error before we were able to evaluate text quality | WIP | No (This kernel is optimized for decoding) |

| PyTorch FlexAttention | Coherent | WIP | WIP |

Figure 5. Table of combinations we tried with different Flash Attention Kernels

The above table summarizes what we observed out-of-the box. With some effort we expect that kernels 2-5 can be modified to meet the above criteria. However, this also shows that having a kernel that works for benchmarking is often only the start of having it usable as an end to end production kernel.

We chose to use the AMD flash attention kernel in our subsequent tests as it can be compiled via torch.compile and produces legible output in both eager and compiled mode.

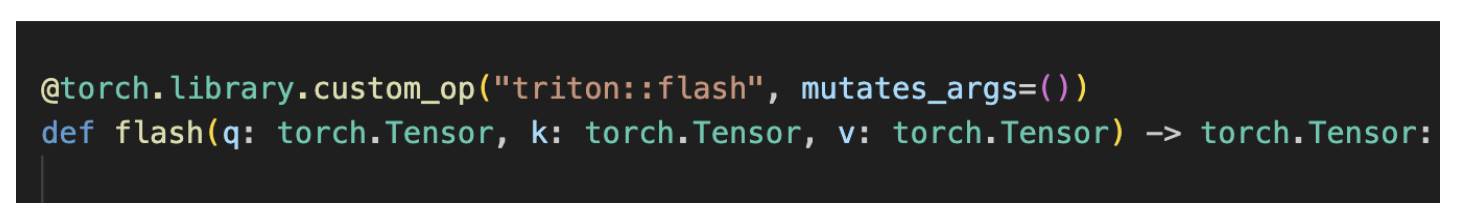

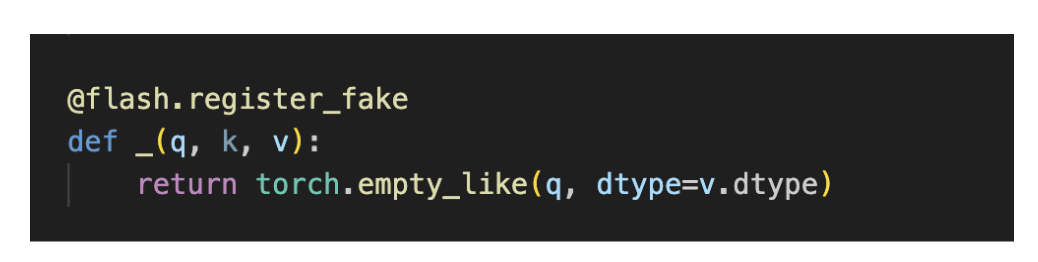

To satisfy torch.compile compatibility with the AMD flash attention kernel, we had to define it as a torch custom operator. This process is explained in detail here. The tutorial link discusses how to wrap a simple image crop operation. However, we note that wrapping a more complex flash attention kernel follows a similar process. The two step approach is as follows:

- Wrap the function into a PyTorch Custom Operator

- Add a FakeTensor Kernel to the operator, which given the shapes of the input tensors of flash (q, k and v) provides a way to compute the output shape of the flash kernel

After defining the Triton flash kernel as a custom op, we were able to successfully compile it for our E2E runs.

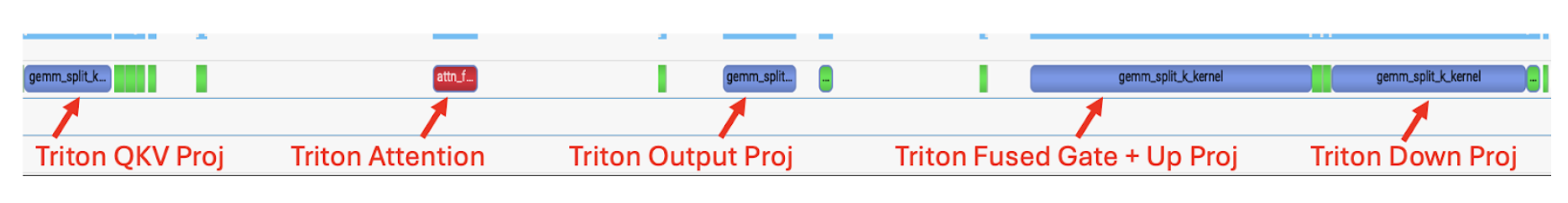

Figure 6. Trace of Llama3-8B with torch.compile, after swapping in Triton matmul and Triton flash attention kernels

From Figure 5, we note that now, after integrating both the SplitK matrix multiplication kernel, the torch op wrapped flash attention kernel, and then running torch.compile, we are able to achieve a forward pass that uses 100% Triton computation kernels.

7.0 End-to-End Benchmarks

We performed end-to-end measurements on NVIDIA H100s and A100s (single GPU) with Granite-8B and Llama3-8B models. We performed our benchmarks with two different configurations.

The Triton kernel configuration uses:

- Triton SplitK GEMM

- AMD Triton Flash Attention

The CUDA Kernel configuration uses:

- cuBLAS GEMM

- cuDNN Flash Attention – Scaled Dot-Product Attention (SDPA)

We found the following throughput and inter-token latencies for both eager and torch compiled modes, with typical inference settings:

| GPU | Model | Kernel Config | Median Latency (Eager) [ms/tok] | Median Latency (Compiled) [ms/tok] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H100 | Granite-8B | Triton | 27.42 | 11.59 |

| CUDA | 18.84 | 9.50 | ||

| Llama3-8B | Triton | 20.36 | 10.61 | |

| CUDA | 16.59 | 8.59 | ||

| A100 | Granite-8B | Triton | 53.44 | 16.88 |

| CUDA | 37.13 | 14.25 | ||

| Llama3-8B | Triton | 44.44 | 17.94 | |

| CUDA | 32.45 | 12.96 |

Figure 7. Granite-8B and Llama3-8B Single Token Generation Latency on H100 and A100,

(batch size = 2, input sequence length = 512, output sequence length = 256)

To summarize, the Triton models can get up to 78% of the performance of the CUDA models on the H100 and up to 82% on the A100.

The performance gap can be explained by the kernel latencies we observe for matmul and flash attention, which are discussed in the next section.

8.0 Microbenchmarks

| Kernel | Triton [us] | CUDA [us] |

|---|---|---|

| QKV Projection Matmul | 25 | 21 |

| Flash Attention | 13 | 8 |

| Output Projection Matmul | 21 | 17 |

| Gate + Up Projection Matmul | 84 | 83 |

| Down Projection Matmul | 58 | 42 |

Figure 8. Triton and CUDA Kernel Latency Comparison (Llama3-8B on NVIDIA H100)

Input was an arbitrary prompt (bs=1, prompt = 44 seq length), decoding latency time

From the above, we note the following:

-

Triton matmul kernels are 1.2-1.4x slower than CUDA

-

AMDs Triton Flash Attention kernel is 1.6x slower than CUDA SDPA

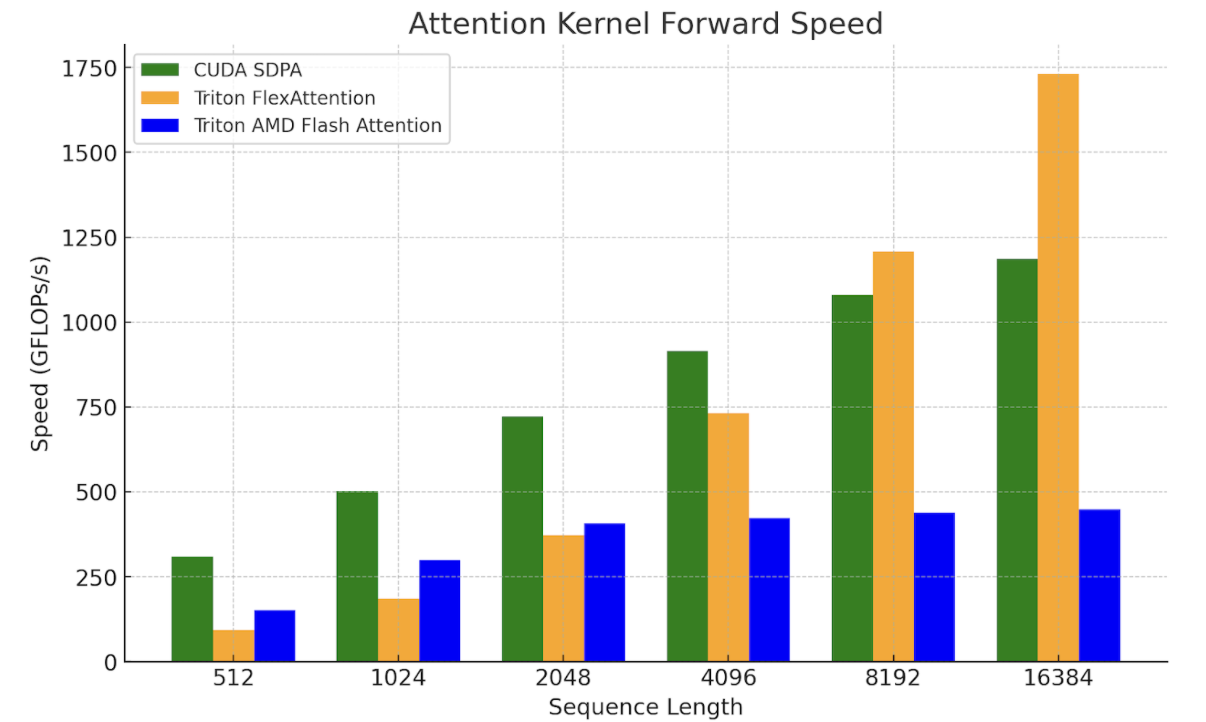

These results highlight the need to further improve the performance of kernels that are core primitives like GEMM and Flash Attention. We leave this as future research, as recent works (e.g. FlashAttention-3, FlexAttention) provide ways to leverage the underlying hardware better as well as Triton pathways that we hope to be able to build on to produce greater speedups. To illustrate this, we compared FlexAttention with SDPA and AMD’s Triton Flash kernel.

We are working to verify E2E performance with FlexAttention. For now, initial microbenchmarks with Flex show promise for longer context lengths and decoding problem shapes, where the query vector is small:

Figure 9. FlexAttention Kernel Benchmarks on NVIDIA H100 SXM5 80GB

(batch=1, num_heads=32, seq_len=seq_len, head_dim=128)

9.0 Future Work

For future work we plan to explore ways to further optimize our matmuls that leverage the hardware better, such as this blog we published on utilizing TMA for H100, as well as different work decompositions (persistent kernel techniques like StreamK etc.) to get greater speedups for our Triton-based approach. For flash attention, we plan to explore FlexAttention and FlashAttention-3 as the techniques used in these kernels can be leveraged to help further close the gap between Triton and CUDA.

We also note that our prior work has shown promising results for FP8 Triton GEMM kernel performance versus cuBLAS FP8 GEMM, thus in a future post we will explore E2E FP8 LLM inference.