[July 20, 2021] Our work was recently covered by the New York Times here. You can also find a technical preprint here.

tl;dr.

With the rise of large online computer science courses, there

is an abundance of high-quality content. At the same time, the sheer

size of these courses makes high-quality feedback to student work more

and more difficult. Talk to any educator, and they will tell you how

instrumental instructor feedback is to a student’s learning process.

Unfortunately, giving personalized feedback isn’t cheap: for a large

online coding course, this could take months of labor. Today, large

online courses either don’t offer feedback at all or take shortcuts that

sacrifice the quality of the feedback given.

Several computational approaches have been proposed to automatically

produce personalized feedback, but each falls short: they either require

too much upfront work by instructors or are limited to very simple

assignments. A scalable algorithm for feedback to student code that

works for university-level content remains to be seen. Until now, that

is. In a recent paper, we proposed a new AI system based on

meta-learning that trains a neural network to ingest student code and

output feedback. Given a new assignment, this AI system can quickly

adapt with little instructor work. On a dataset of student solutions to

Stanford’s CS106A exams, we found the AI system to match human

instructors in feedback quality.

To test the approach in a real-world setting, we deployed the AI system

at Code in Place 2021, a large online computer science course spun out

of Stanford with over 12,000 students, to provide feedback to an

end-of-course diagnostic assessment. The students’ reception to the

feedback was overwhelmingly positive: across 16,000 pieces of feedback

given, students agreed with the AI feedback 97.9% of the time, compared

to 96.7% agreement to feedback provided by human instructors. This is,

to the best of our knowledge, the first successful deployment of machine

learning based feedback to open-ended student work.

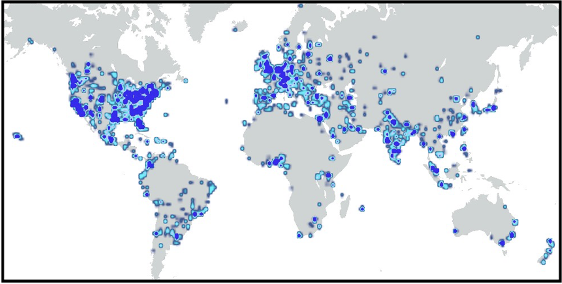

In the middle of the pandemic, while everyone is forced to social

distance in the confines of their own homes, thousands of people across

the world were hard at work figuring out why their code was stuck in an

infinite loop. Stanford CS106A, one of the university’s most popular

courses and its largest introductory programming offering with nearly

1,600 students every year, grew even bigger. Dubbed Code in Place,

CS106A instructors Chris Piech, Mehran Sahami and Julie Zelenski wanted

to make the curriculum and teaching philosophy of CS106A publicly

available as an uplifting learning experience for students and adults

alike during a difficult time. In its inaugural showing in April ‘20,

Code in Place pulled together 908 volunteer teachers to run an online

course for 10,428 students from around the world. One year later, with

the pandemic still in full force in many areas of the world, Code in

Place kicked off again, growing to over 12,000 students and 1,120

volunteer teachers.

While crowd-sourcing a teaching team did make a lot of things possible

for Code in Place that usual online courses lack, there are still limits

to what can be done with a class of this scale. In particular, one of

the most challenging hurdles was providing high-quality feedback to

10,000 students.

What is feedback?

Everyone knows high quality content is an important

ingredient for learning, but another equally important but more subtle

ingredient is getting high quality feedback. Knowing the breakdown of

what you did well and what the areas for improvement are, is fundamental

to understanding. Think back to when you first got started programming:

for me, small errors that might be obvious to someone more experienced,

cause a lot of frustration. This is where feedback comes in, helping

students overcome this initial hurdle with instructor guidance.

Unfortunately, feedback is something online code education has struggled

with. With popular “massively open online courses” (MOOCs), feedback on

student code boils down to compiler error messages, standardized

tooltips, or multiple-choice quizzes.

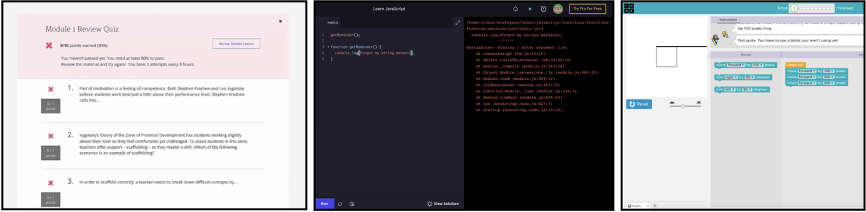

You can find an example of each below. On the left, multiple choice

quizzes are simple to grade and can easily assign numeric scores to

student work. However, feedback is limited to showing the right answer,

which does little to help students understand their underlying

misconceptions. The middle picture shows an example of an opaque

compiler error complaining about a syntax issue. As a beginner learning

to code, error messages are very intimidating and difficult to

interpret. Finally, on the right, we see an example of a standardized

tooltip: upon making a mistake, a pre-specified message is shown.

Pre-specified messages tend to be very vague: here, the tooltip just

tells us our solution is wrong and to try something different.

It makes a lot of sense why MOOCs settle for subpar feedback: it’s

really difficult to do otherwise! Even for Stanford CS106A, the teaching

team is constantly fighting the clock in office hours in an attempt to

help everyone. Outside of Stanford, where classes may be more

understaffed, instructors are already unable to provide this level of

individualized support. With large online courses, the sheer size makes

any hope of providing feedback unimaginable. Last year, Code in Place

gave a diagnostic assessment during the course for students to summarize

what they have learned. However, there was no way to give feedback

scalably to all these student solutions. The only option was to release

the correct solutions online for students to compare to their own work,

displacing the burden of feedback onto the students.

Code in Place and its MOOC cousins are examples of a trend of education

moving online, which might only grow given the lasting effects of the

pandemic. This shift surfaces a very important challenge: can we provide

feedback at scale?

The feedback challenge.

In 2014, Code.org, one

of the largest online platforms for code education, launched an

initiative to crowdsource thousands of instructors to provide feedback

to student solutions [1,2]. The hope of the initiative was to tag enough

student solutions with feedback so that for a new student, Code.org

could automatically provide feedback by matching the student’s solution

to a bank of solutions already annotated with feedback by an instructor.

Unfortunately, Code.org quickly found that even after thousands of

aggregate hours spent providing feedback, instructors were only

scratching the surface. New students were constantly coming up with new

mistakes and new strategies. The initiative was cancelled after two

years and has not been reproduced since.

We might ask: why did this happen? What is it about feedback that makes

it so difficult to scale? In our research, we came up with two parallel

explanations.

First, providing feedback to student code is hard work. As an

instructor, every student solution requires me to reason about the

student’s thought process to uncover what misconceptions they might have

had. If you have ever had to debug someone else’s code, providing

feedback is at least as hard as that. In a previous research paper, we found that producing

feedback for only 800 block-based programs took a teaching team a

collective 24.9 hours. If we were to do that for all of Code in Place,

it would take 8 months of work.

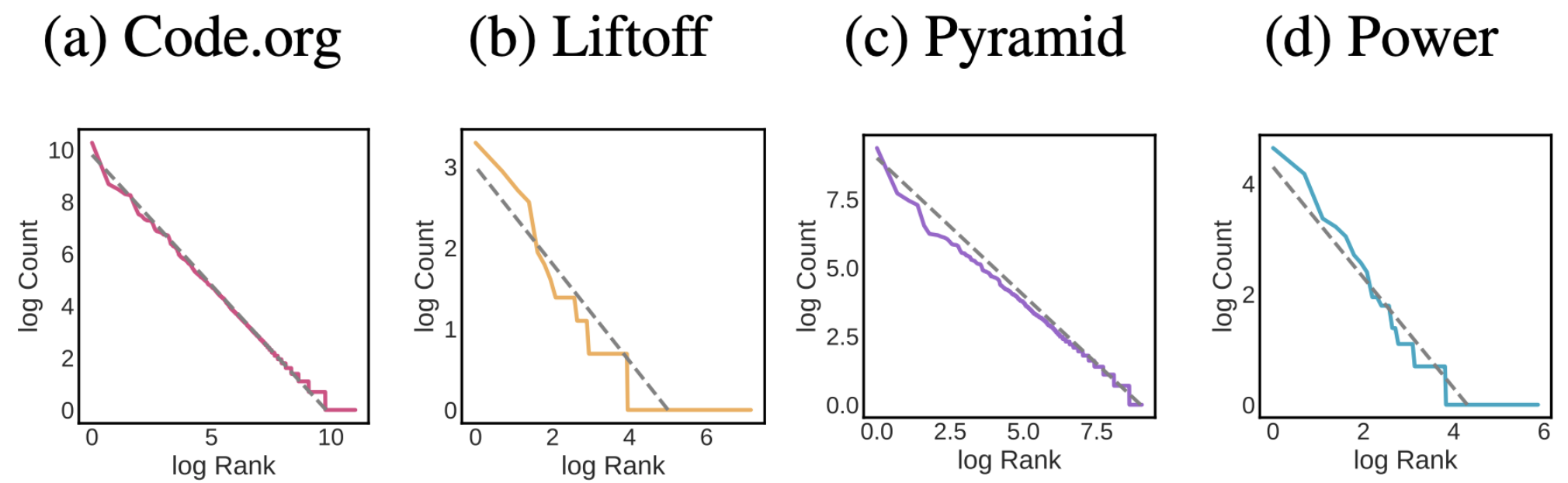

Second, students approach the same programming problem in an exponential

number of ways. Almost every new student solution will be unique, and a

single misconception can manifest itself in seemingly infinite ways. As

a concrete example, even after seeing a million solutions to a Code.org

problem, there is still a 15% chance that a new student generates a

solution never seen before. Perhaps not coincidentally, it turns out the

distribution of student code closely follows the famous Zipf

distribution, which reveals an extremely “long tail” of rare solutions

that only one student will ever submit. Moreover, this close

relationship to Zipf doesn’t just apply to Code.org; it is a much more

general phenomenon. We see similar patterns for student work for

university level programming assignments in Python and Java, as well as

free response solutions to essay-like prompts.

So, if asking instructors to manually provide feedback at scale is

nearly impossible, what else can we do?

Automating feedback.

“If humans can’t do it, maybe machines

can” (famous last words). After all, machines process information a lot

faster than humans do. There have been several approaches applying

computational techniques to provide feedback, the simplest of which is

unit tests. An instructor can write a collection of unit tests for the

core concepts and use them to evaluate student solutions. However, unit

tests expect student code to compile and, often, student code does not

due to errors. If we wish to give feedback on partially complete

solutions, we need to be able to handle non-compiling code. Given the

successes of AI and deep learning in computer vision and natural

language, there have been attempts of designing AI systems to

automatically provide feedback, even when student code does not compile.

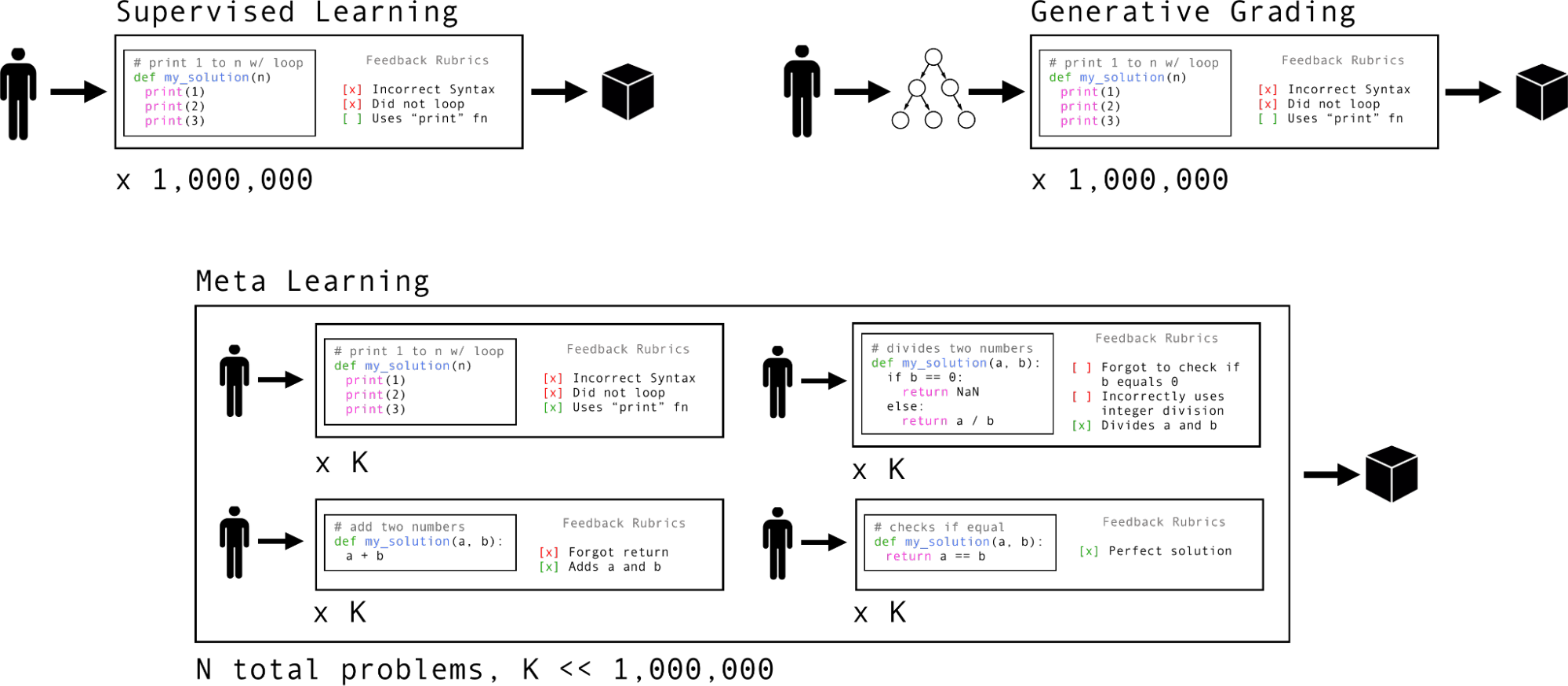

Supervised Learning

Given a dataset of student code, we can ask an

instructor to provide feedback for each of the solutions, creating a

labeled dataset. This can be used to train a deep learning model to

predict feedback for a new student solution. While this is great in

theory, in practice, compiling a sufficiently large and diverse dataset

is difficult. In machine learning, we are accustomed to datasets with

millions of labeled examples since annotating an image is both cheap and

requires no domain knowledge. On the other hand, annotating student

code with feedback is both time-consuming and needs expertise, limiting

datasets to be a few thousand examples in size. Given the Zipf-like

nature of student code, it is very unlikely that a dataset of this size

can capture all the different ways students approach a problem. This is

reflected in practice as supervised attempts perform poorly on new

student solutions.

Generative Grading

While annotating student code is difficult work,

instructors are really good at thinking about how students would tackle

a coding problem and what mistakes they might make along the way.

Generative grading [2,3] asks instructors to distill this intuition

about student cognition into an algorithm called a probabilistic

grammar. Instructors specify what misconceptions a student might make

and how that translates to code. For example, if a student forgets a

stopping criterion resulting in an infinite loop, their program likely

contains a “while” statement with no “break” condition. Given such an

algorithm, we can run it forward to generate a full student solution

with all misconceptions already labeled. Doing this repeatedly, we

curate a large dataset to train a supervised model. This approach was

very successful on block-based code, where performance rivaled human

instructors. However, the success of it hinges on a good algorithm.

While tractable for block-based programs, it became exceedingly

difficult to build a good algorithm for university level assignments

where student code is much more complex.

The supervised approach requires the instructor to curate a dataset of

student solutions with feedback where as the generative grading approach

requires the instructor to build an algorithm to generate annotated

data. In contrast, the meta-learning approach requires the instructor to

annotate feedback for K examples across N programming problems. K is

typically very small (~10) and N not much larger (~100).

Meta-learning how to give feedback.

So far, neither approach is quite

right. In different ways, supervised learning and generative grading

both expect too much from the instructor. As they stand, for every new

coding exercise, the instructor would have to put in days, if not weeks

to months of effort. In an ideal world, we would shift more of the

burden of feedback onto the AI system. While we would still like

instructors to play a role, the AI system should bear the onus of

quickly adapting to every new exercise. To accomplish this, we built an

AI system to “learn how to learn” to give feedback.

Meta-learning is an old idea from the 1990s [9, 10] that has seen a

resurgence in the last five years. Recall that in supervised learning a

model is trained to solve a single task; in meta-learning, we solve many

tasks at once. The catch is that we are limited to a handful of labeled

examples for every task. Whereas supervised learning gets lots of labels

for one task, we spread the annotation effort evenly across many tasks,

leaving us with a few labels per task. In research literature, this is

called the few-shot classification problem. The upside to meta-learning

is that after training, if your model is presented with a new task that

it has not seen before, it can quickly adapt to solve it with only a

“few shots” (i.e., a few annotations from the new task).

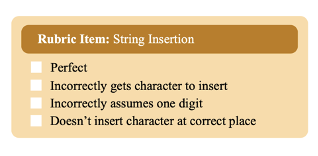

So, what does meta-learning for feedback look like? To answer that, we

first need to describe what composes a “task” in the world of

educational feedback. Last year, we compiled a dataset of student

solutions from eight CS106A exams collected over the last three academic

years. Each exam consists of four to six programming exercises in which

the student must write code (but is unable to run or compile it for

testing). Every student solution is annotated by an instructor using a

feedback rubric containing a list of misconceptions tailored to a single

problem. As an example, consider a coding exercise that asks the student

to write a Python program that requires string insertion. A potential

feedback rubric is shown in the left image: possible misconceptions are

inserting at the wrong location or inserting the wrong string. So, we

can treat every misconception as its own task. The string insertion

example would comprise of four tasks.

One of the key ideas of this approach is to frame

the feedback challenge as a few-shot classification problem. Remember

that the reasons why previous methods for automated feedback struggled

were the (1) high cost of annotation and (2) diversity of student

solutions. Casting feedback as a few-shot problem cleverly circumvents

both challenges. First, meta-learning can leverage previous data on old

exams to learn to provide feedback to a new exercise with very little

upfront cost. We only need to label a few examples for the new exercise

to adapt the meta-learner and importantly, do not need to train a new

model from scratch. Second, there are two ways to handle diversity: you

can go for “depth” by training on a lot of student solutions for a

single problem to see different strategies, or you can go for “breadth”

and get sense of diverse strategies through student solutions on a lot

of different problems. Meta-learning focuses its efforts on capturing

“breadth”, accumulating more generalizable knowledge that can be shared

across problems.

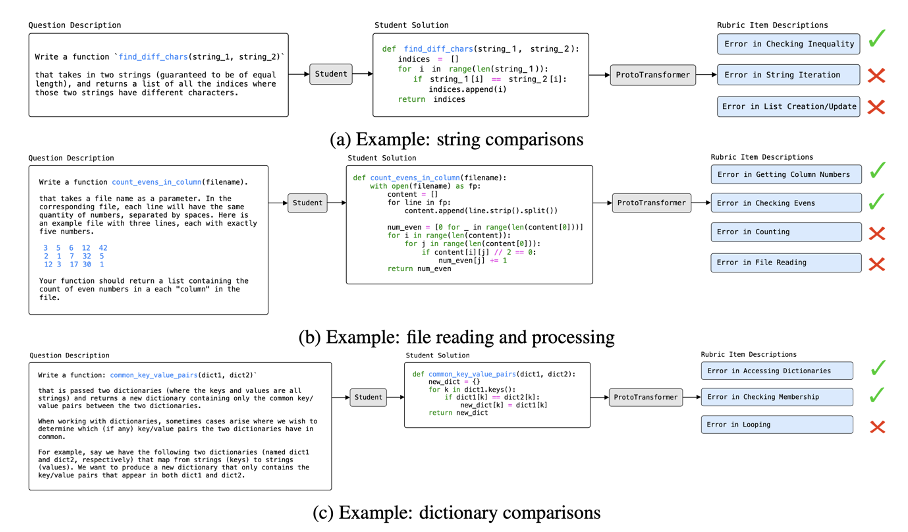

We will leave the details of the meta-learner to the technical report.

In short, we propose a new deep neural network called a ProtoTransformer

Network that combines the strengths of BERT from natural language

processing and Prototypical Networks from few-shot learning literature.

This architecture, in tandem with technical innovations – creating

synthetic tasks for code, self-supervised pretraining on unlabeled code,

careful encoding of variable and function names, and adding question and

rubric descriptions as side information – together produce a highly

performant AI system for feedback. To help ground this in context, we

include three examples on the bottom of the last page of the AI system

predicting feedback to student code. The predictions were taken from

actual model output on student submissions.

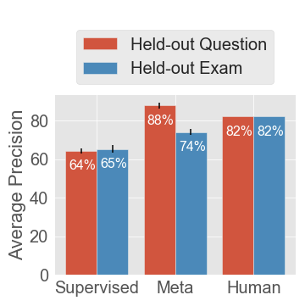

Main Results

Aside from looking at qualitative examples, we can

measure its performance quantitatively by evaluating the correctness of

the feedback an AI system gave on exercises not used in training. A

piece of feedback is considered correct if a human instructor annotated

the student solution with it.

We consider two experimental settings for evaluation:

-

Held-out Questions: we randomly pick 10% of questions across all exams

to evaluate the meta-learner. This simulates instructors providing

feedback for part of every exam, leaving a few questions for the AI to

give feedback for. -

Held-out Exams: we hold out an entire exam for evaluation. This is a

much harder setting as we know nothing about the new exam but also most

faithfully represents an autonomous feedback system.

We measure the performance of human instructors by asking several

teaching assistants to grade the same student solution and recording

agreement. We also compare the meta-learner to a supervised baseline. As

shown in the graph on the previous page, the meta-learner outperforms

the supervised baseline by up to 24 percentage points, showcasing the

utility of meta-learning. More surprisingly, we find that the

meta-learner surpasses human performance by 6% in held-out questions.

However, there is still room for improvement as we fall short 8% to

human performance on held-out exams – a harder challenge. Despite this,

we find these results encouraging: previous methods for feedback could

not handle the complexity of university assignments, let alone approach,

or match the performance of instructors.

Automated feedback for Code in Place.

Taking a step back, we began

with the challenge of feedback, an important ingredient to a student’s

learning process that is frustratingly difficult to scale, especially

for large online courses. Many attempts have been made towards this,

some based on crowdsourcing human effort and others based on

computational approaches with and without AI, but all of which have

faced roadblocks. In late May ‘21, we built and tested an approach based

on meta-learning, showing surprisingly strong results on university

level content. But admittedly, the gap between ML research and

deployment can be large, and it remained to be shown that our approach

can give high quality feedback at scale in a live application. Come

June, Code in Place ‘21 was gearing up for its diagnostic assessment.

In an amazing turnout, Code in Place ‘21 had 12,000 students. But

grading 12,000 students each solving 5 problems would be beyond

intractable. To put it into numbers, it would take 8 months of human

labor, or more than 400 teaching assistants working standard

nine-to-five shifts to manually grade all 60,000 solutions.

The Code in Place ‘21 diagnostic contained five new questions that were

not in the CS106A dataset used to train the AI system. However, the

questions were similar in difficulty and scope, and correct solutions

were roughly the same length as those in CS106A. Because the AI system

was trained with meta-learning, it could quickly adapt to these new

questions. Volunteers from the teaching team helped annotate a small

portion of the student solutions that the AI meta-learning algorithm

requires.

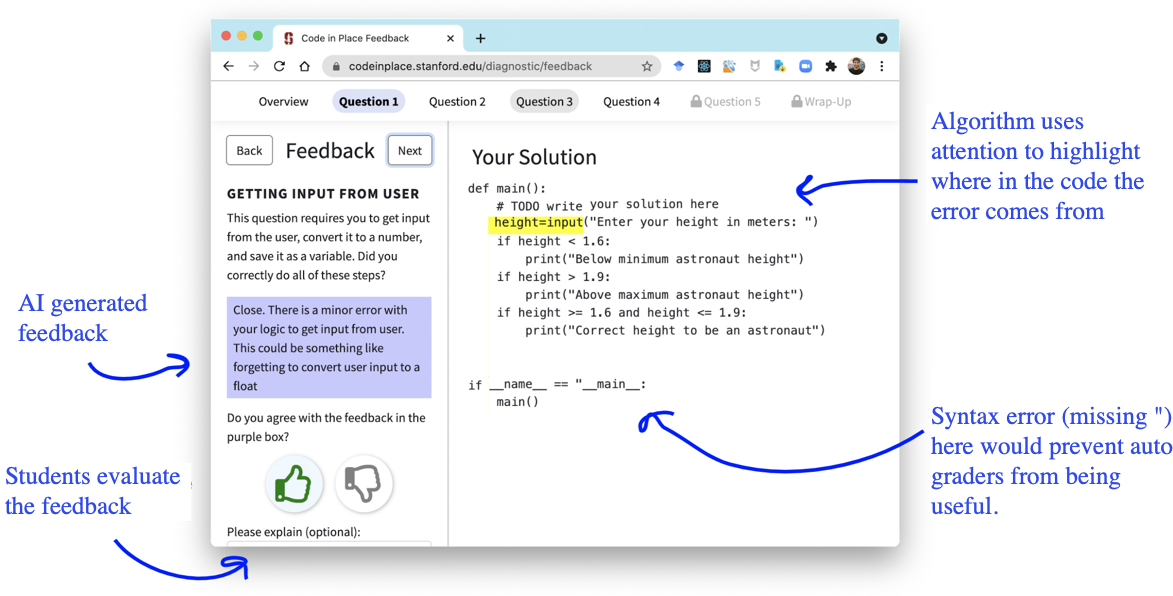

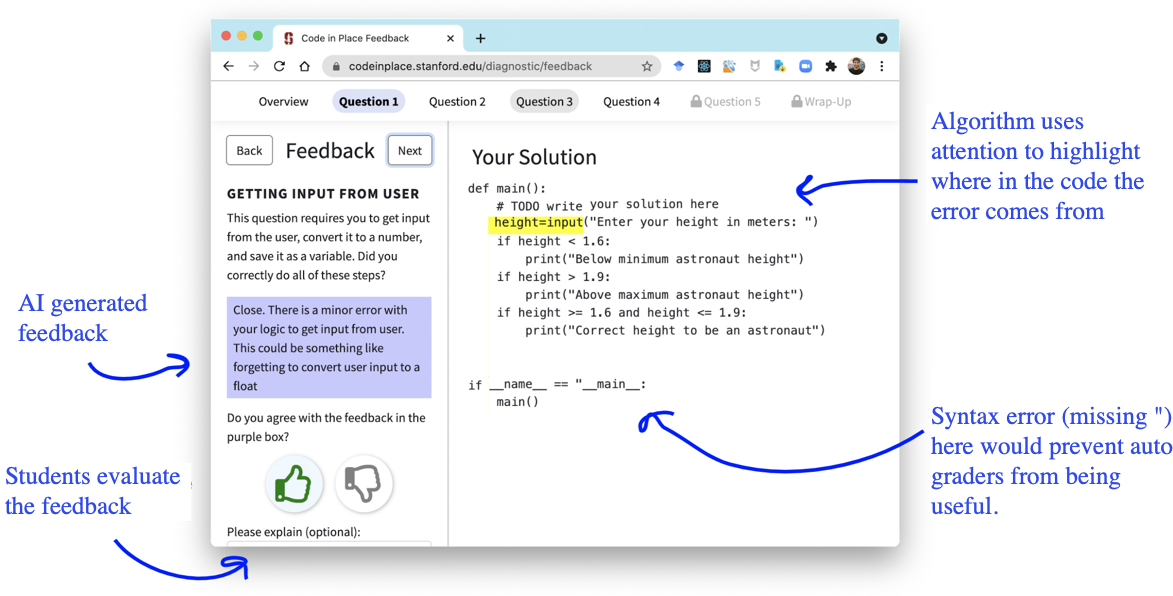

To showcase feedback to students, we were joined by Alan Chang and together we built an application for students

to see their solutions and AI feedback (see image above). We were

transparent in informing students that an AI was providing feedback. For

each predicted misconception, we associated it with a message (shown in

the blue box) to the student. We carefully crafted the language of these

messages to be helpful and supportive of the student’s learning. We also

provided finer grained feedback by highlighting portions of the code

that the AI system weighted more strongly in making its prediction. In

the image above, the student forgot to cast the height to an integer. In

fact, the highlighted line should be height = int(input(…)), which the

AI system picked up on.

Human versus AI Feedback

For each question, we asked the student to

rate the correctness of the feedback provided by clicking either a

“thumbs up” or a “thumbs down” before they can proceed to the next

question (see lower left side of the image above). Additionally, after a

student reviewed all their feedback, we asked them to rate the AI system

holistically on a five-point scale. As part of the deployment, some of

the student solutions were given feedback by humans but students did not

know which ones. So, we can compare students’ holistic and per-question

rating when given AI feedback versus instructor feedback.

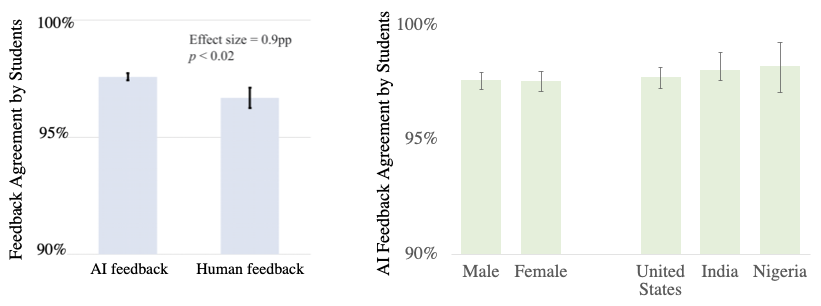

Here’s what we found:

- 1,096 students responded to a survey after receiving 15,134 pieces

of feedback. The reception was overwhelmingly positive: Across all

15k pieces of feedback, students agreed with AI suggestions 97.9% ±

0.001 of the time. - We compared student agreement with AI feedback against agreement

with instructor feedback, where we surprisingly found the AI system

surpass human instructors: 97.9% > 96.7% (p-value 0.02). The

improvement was driven by higher student ratings on constructive

feedback – times when the algorithm suggested an improvement. - On the five-point scale, the average holistic rating of usefulness

by students was 4.6 ± 0.018 out of 5. - Given the wide diversity of students participating in Code in Place,

we segmented the quality of AI feedback by gender and country, where

we found no statistically significant difference across

groups.

To the best of our knowledge, this was both the first successful

deployment of AI-driven feedback to open-ended student work and the

first successful deployment of prototype networks in a live application.

With promising results in both a research and a real-world setting, we

are optimistic about the future of artificial intelligence in code

education and beyond.

How could AI feedback impact teaching?

A successful deployment of an

automated feedback system raises several important questions about the

role of AI in education and more broadly, society.

To start, we emphasize that what makes Code in Place so successful is

its amazing teaching team made up of over 1,000 section leaders. While

feedback is an important part of the learning experience, it is one

component of a larger ecosystem. We should not incorrectly conclude from

our results that AI can automate teaching or replace instructors – nor

should the system be used for high-stakes grading. Instead, we should

view AI feedback as another tool in the toolkit for instructors to

better shape an amazing learning experience for students.

Further, we should evaluate our AI systems with a double bottom line of

both performance and fairness. Our initial experiments suggest that the

AI is not biased but our initial results are being supplemented by a

more thorough audit. To minimize the chance of providing incorrect

feedback to student work, future research should encourage AI systems to

learn to say: “I don’t know”.

Third, we find it important that progress in education research be

public and available for others to critique and build upon.

Finally, this research opens so many directions moving forward. We hope

to use this work to enable teachers to better reach their potential.

Moreover, an AI feedback makes it scalable to study not just students’

final solutions, but the process of how students solve their

assignments. Finally, there is a novel opportunity for computational

approaches towards unraveling the science of how students learn.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Chelsea Finn, Chris Piech, and Noah

Goodman for their guidance. Special thanks to Chris for his support the

last three years through the successes and failures towards AI feedback

prediction. Also, thanks to Alan Cheng, Milan Mosse, Ali Malik, Yunsung

Kim, Juliette Woodrow, Vrinda Vasavada, Jinpeng Song, and John Mitchell

for great collaborations. Thank you to Mehran Sahami, Julie Zelenki,

Brahm Capoor and the Code in Place team who supported this project.

Thank you to the section leaders who provided all the human feedback

that the AI was able to learn from. Thank you to the Stanford Institute

for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (in particular the Hoffman-Yee Research Grant) and the Stanford

Interdisciplinary Graduate Fellowship for their support.