Deep reinforcement learning (RL) has achieved superhuman performance in

problems ranging from data center cooling to video games. RL policies

may soon be widely deployed, with research underway in autonomous driving,

negotiation and automated trading. Many potential applications are

safety-critical: automated trading failures caused Knight Capital to lose

USD 460M, while faulty autonomous vehicles have resulted in loss of

life.

Consequently, it is critical that RL policies are robust: both to naturally

occurring distribution shift, and to malicious attacks by adversaries.

Unfortunately, we find that RL policies which perform at a high-level in normal

situations can harbor serious vulnerabilities which can be exploited by an

adversary.

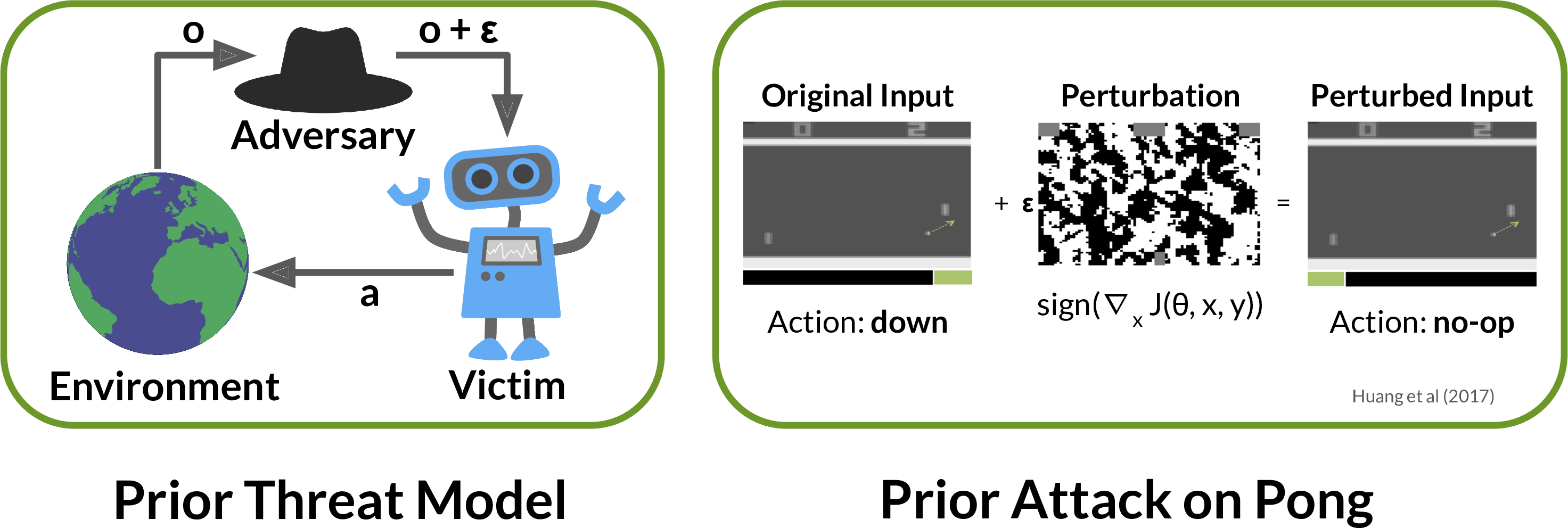

Prior work has shown deep RL policies are vulnerable to small

adversarial perturbations to their observations, similar to adversarial

examples in image classifiers. This threat model assumes the adversary can

directly modify the victim’s sensory observation. Such low-level access is

rarely possible. For example, an autonomous vehicle’s camera image can be

influenced by other drivers, but only to a limited extent. Other drivers cannot

add noise to arbitrary pixels, or make a building disappear.

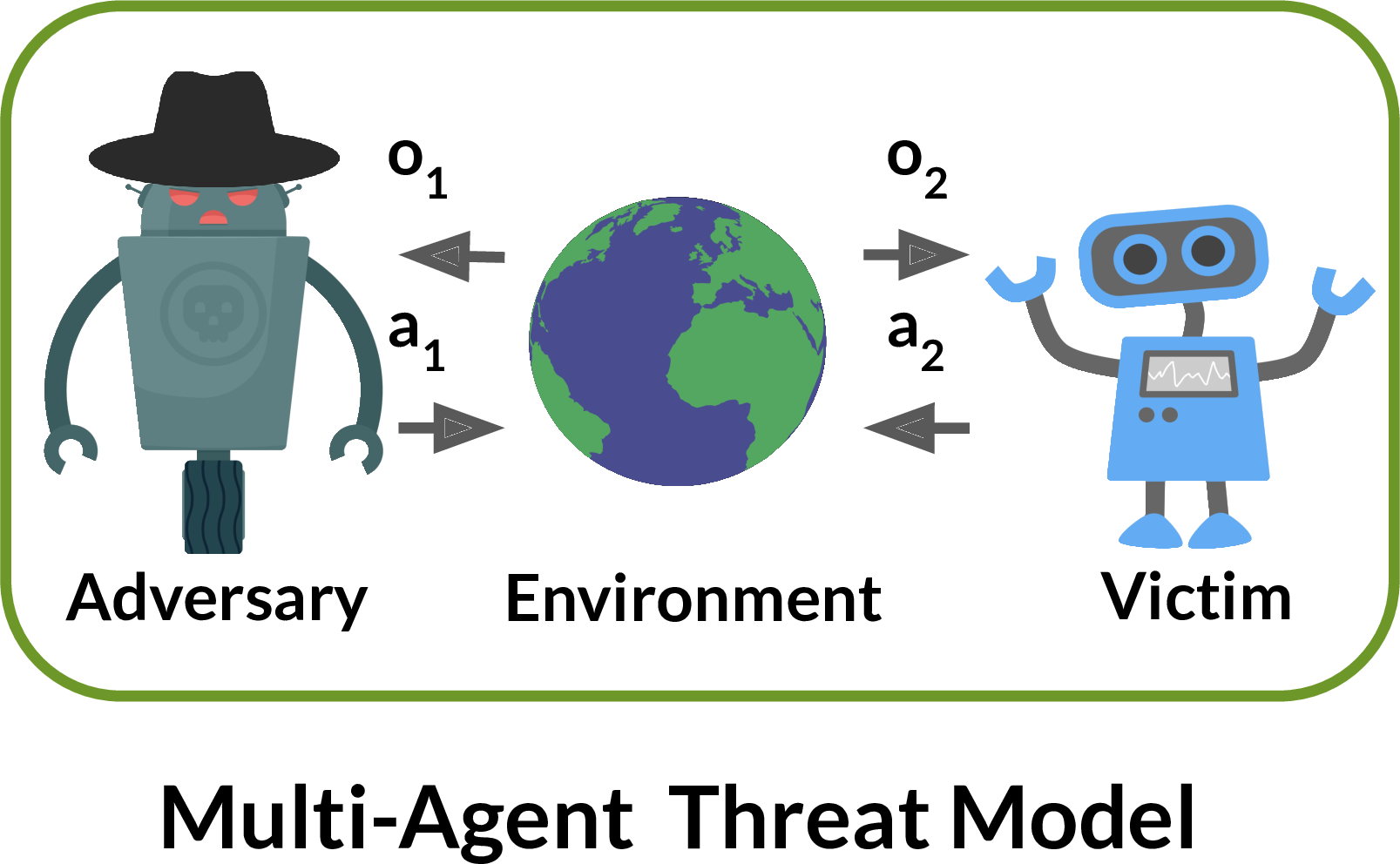

By contrast, we model the victim and adversary as agents in a shared

environment. The adversary can take a similar set of actions to the victim.

These actions may indirectly change the observations the victim sees, but only

in a physically realistic fashion.

Note that if the victim policy were to play a Nash equilibria, it would

not be exploitable by an adversary. We therefore focus on attacking victim

policies trained via self-play, a popular method that approximates Nash

equilibria. While it is known self-play may not always converge, it has

produced highly capable AI systems. For example, AlphaGo and OpenAI

Five have beaten world Go champions, and a professional Dota 2 team.

We find it is still possible to attack victim policies in this more realistic

multi-agent threat model. Specifically, we exploit state-of-the-art policies

trained by Bansal et al from OpenAI in zero-sum games between simulated

Humanoid robots. We train our adversarial policies against a fixed victim

policy, for less than 3% as many timesteps as the victim was trained for. In

other respects, it is trained similarly to the self-play opponents: we use the

same RL algorithm, Proximal Policy Optimization, and the same sparse

reward. Surprisingly, the adversarial policies reliably beat most victims,

despite not standing up and instead flailing on the ground.

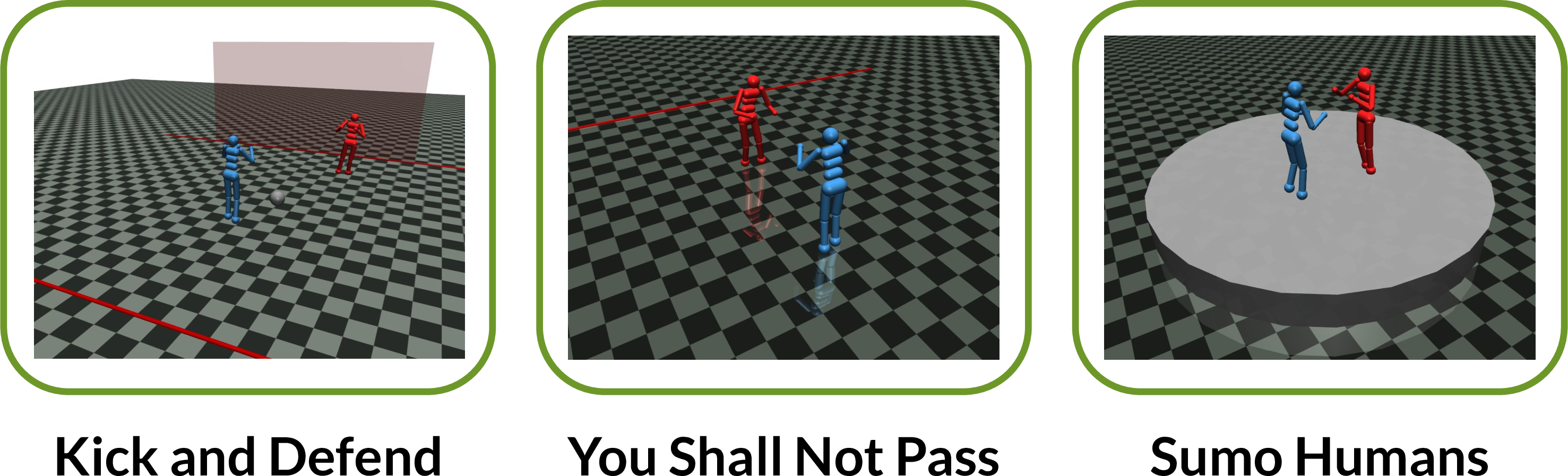

In the video at the top of the post, we show victims in three different

environments playing normal self-play opponents and adversarial policies. The

Kick and Defend environment is a penalty shootout between a victim kicker and

goalie opponent. You Shall Not Pass has a victim runner trying to cross the

finish line, and an opponent blocker trying to prevent them. Sumo Humans has

two agents competing on a round arena to knock out their opponent.

In Kick and Defend and You Shall Not Pass, the adversarial policy never

stands up nor touches the victim. Instead, it positions its body in such a way

to cause the victim’s policy to take poor actions. This style of attack is

impossible in Sumo Humans, where the adversarial policy would immediately

lose if it fell over. Instead, the adversarial policy learns to kneel in the

center in a stable position, which proves surprisingly effective.

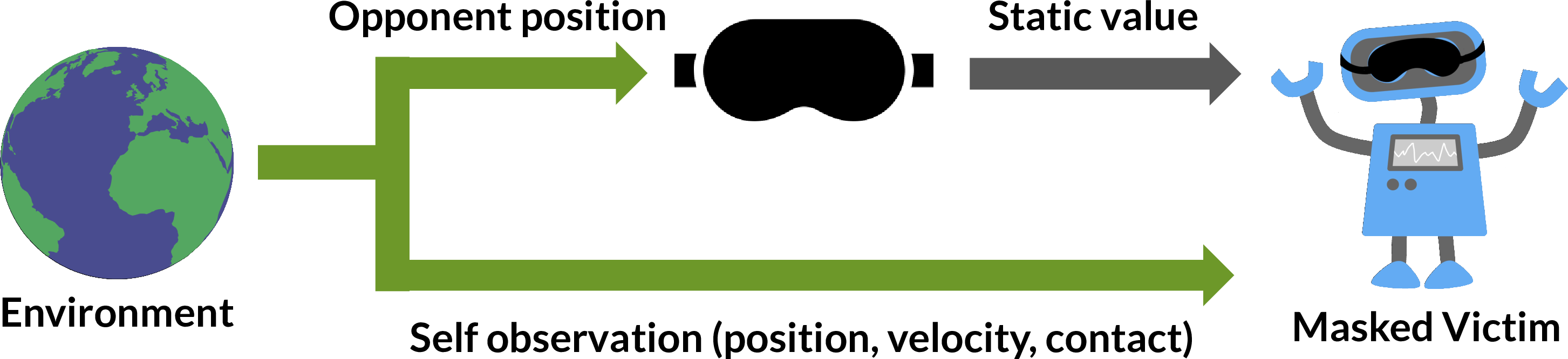

To better understand how the adversarial policies exploit their victims, we

created “masked” versions of victim policies. The masked victim always observes

a static value for the opponent position, corresponding to a typical initial

starting state. This doctored observation is then passed to the original victim

policy.

One would expect performance to degrade when the policy cannot see its

opponent, and indeed the masked victims win less often against normal

opponents. However, they are far more robust to adversarial policies. This

result shows that the adversarial policies win by taking actions to induce

natural observations that are adversarial to the victim, and not by

physically interfering with the victim.

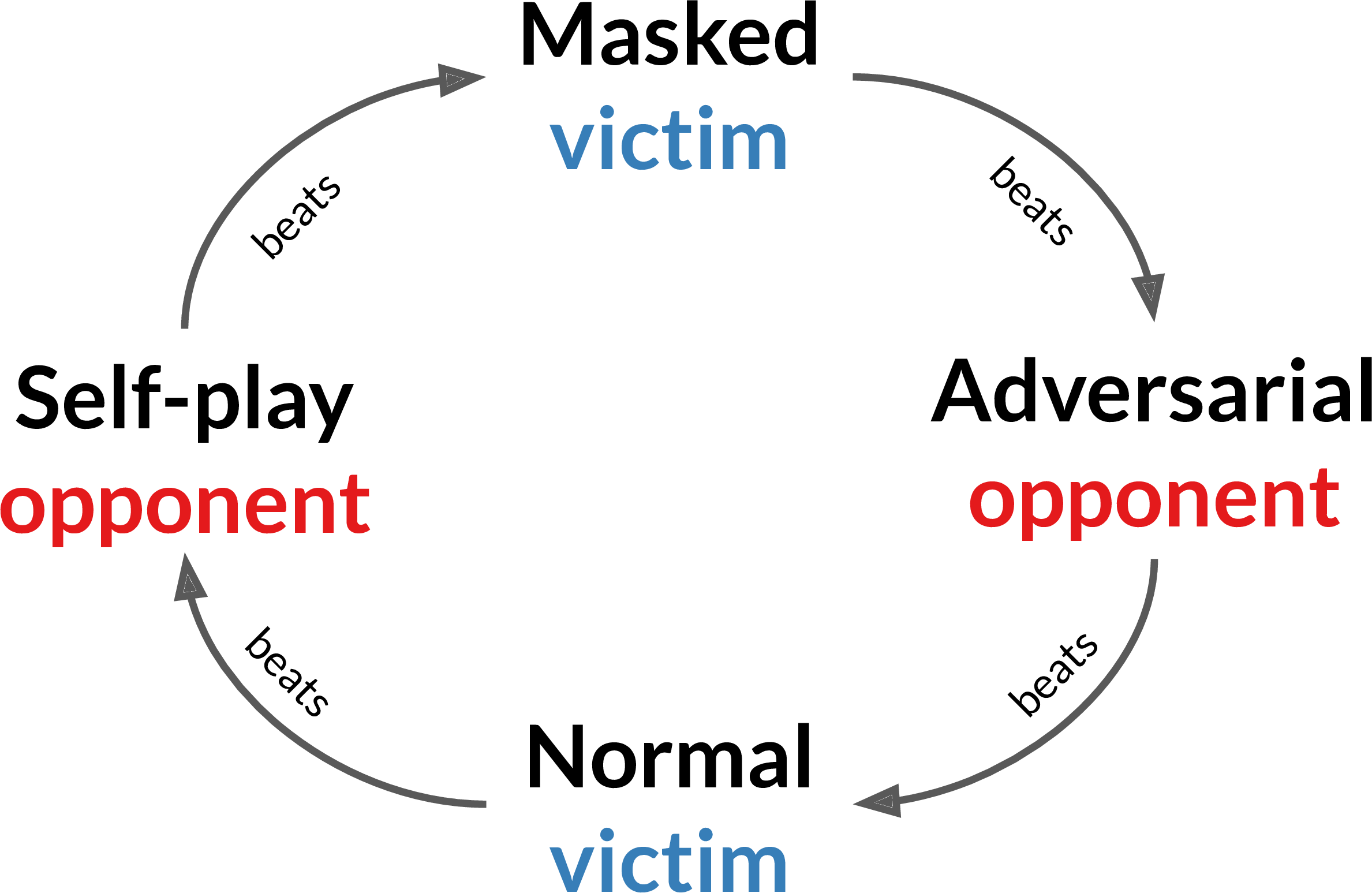

Furthermore, these results show there is a cyclic relationship between the

policies. There is no overall strongest policy: the best policy depends on the

other player’s policy, like in rock-paper-scissors. Technically this is

known as non-transitivity: policy A beats B which beats C, yet C beats A.

This is surprising since these environments’ real-world analogs are

(approximately) transitive: professional human soccer players and sumo

wrestlers can reliably beat amateurs. Self-play assumes

transitivity and so this may be why the self-play policies are vulnerable

to attack.

Of course in general we don’t want to completely blind the victim, since this

hurts performance against normal opponents. Instead, we propose adversarial

training: fine-tuning the victim policy against the adversary that has been

trained against it. Specifically, we fine-tune for 20 million timesteps, the

same amount of experience the adversary is trained with. Half of the episodes

are against an adversary, and the other half against a normal opponent. We find

the fine-tuned victim policy is robust to the adversary it was trained against,

and suffers only a small performance drop against a normal opponent.

However, one might wonder if this fine-tuned victim is robust to our attack

method, or just the adversary it was fine-tuned against. Repeating the attack

method finds a new adversarial policy:

Notably, the new adversary trips the victim up rather than just flailing

around. This suggests our new policies are meaningfully more robust (although

there may of course be failure modes we haven’t discovered).

The existence of adversarial policies has significant implications for the

training, understanding and evaluation of RL policies. First, adversarial

policies highlight the need to move beyond self-play. Promising approaches

include iteratively applying the adversarial training defence above, and

population-based training which naturally trains against a broader range

of opponents.

Second, this attack shows that RL policies can be vulnerable to adversarial

observations that are on the manifold of naturally occurring data. By contrast,

most prior work on adversarial examples has produced physically unrealistic

perturbed images.

Finally, these results highlight the limitations of current evaluation

methodologies. The victim policies have strong average-case performance against

a range of both normal opponents and random policies. Yet their worst-case

performance against adversarial policies is extremely poor. Moreover, it would

be difficult to find this worst-case by hand: the adversarial policies do not

seem like challenging opponents to human eyes. We would recommend testing

safety-critical policies by adversarial attack, constructively lower bounding

the policies’ exploitability.

To find out more, check out our paper or visit the project website

for more example videos.