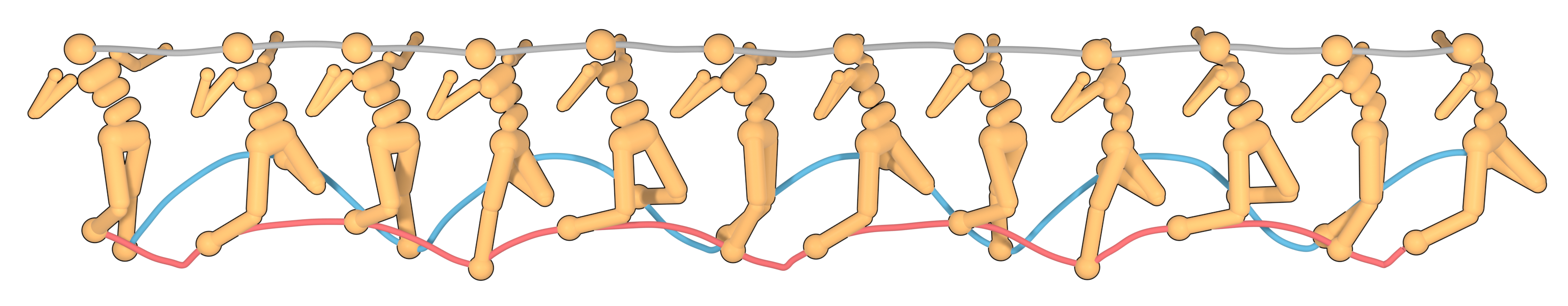

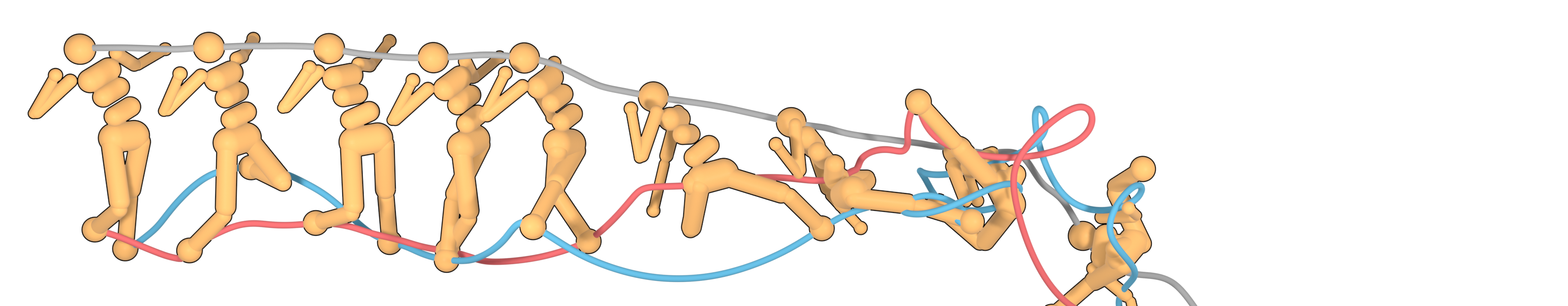

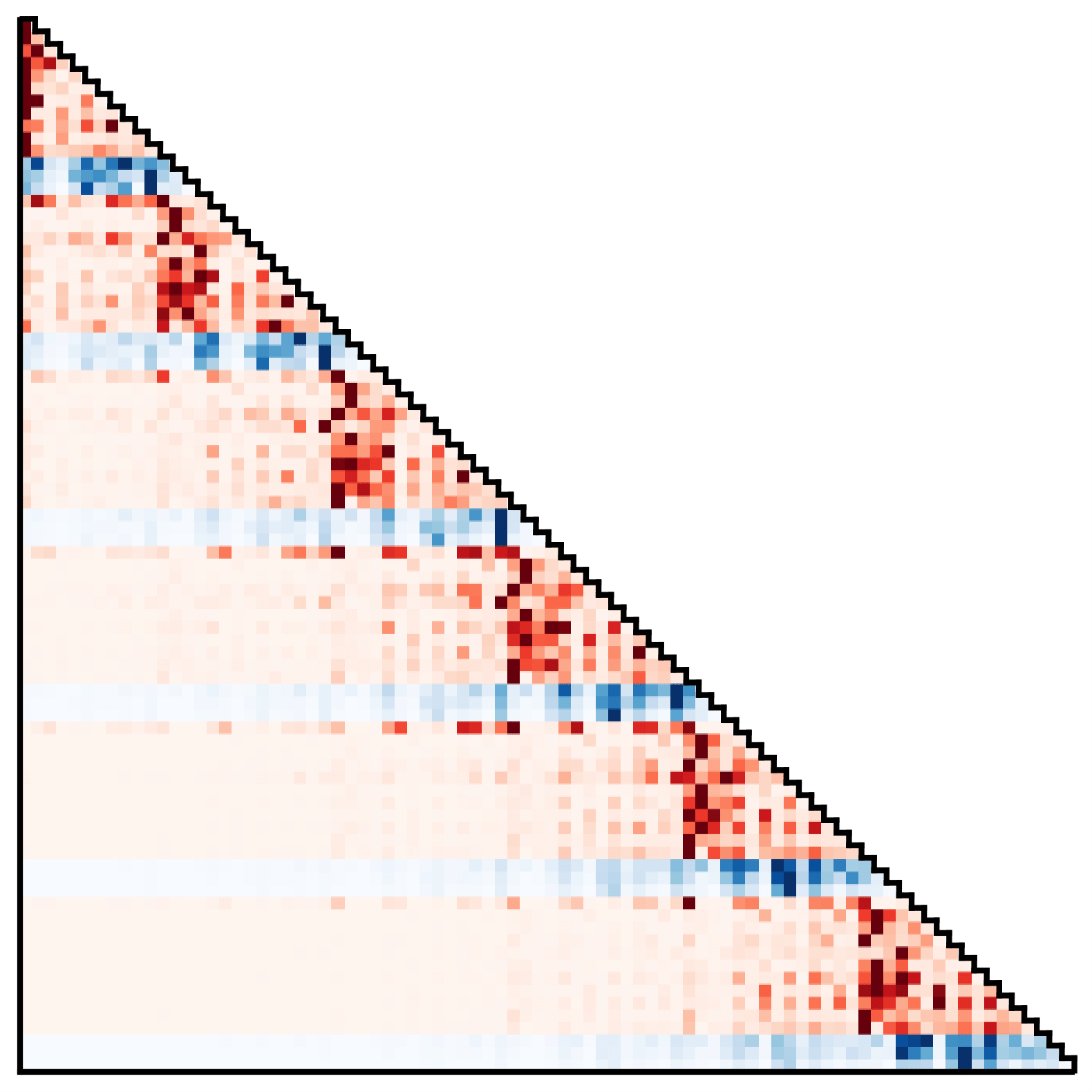

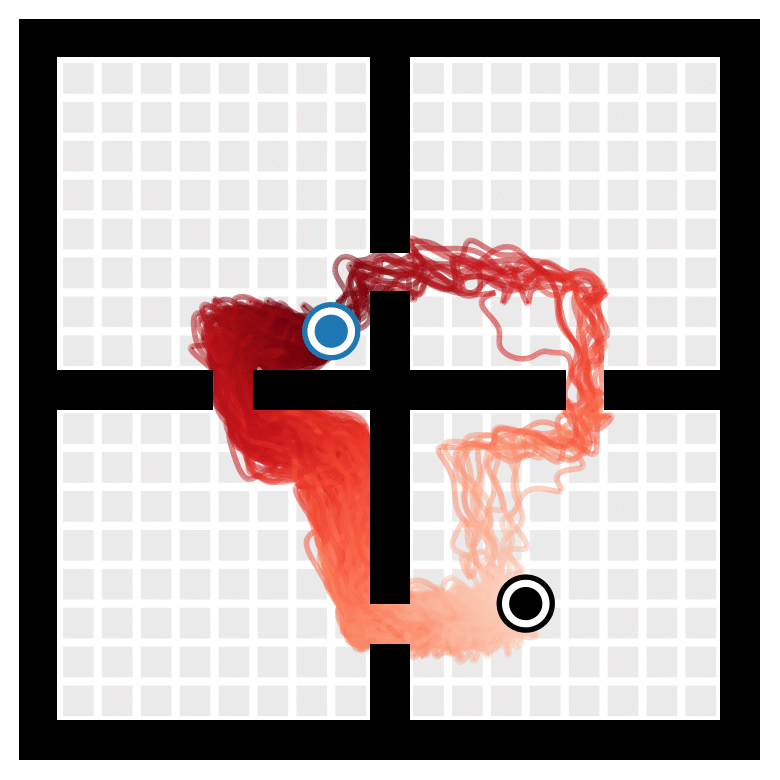

Long-horizon predictions of (top) the Trajectory Transformer compared to those of (bottom) a single-step dynamics model.

Modern machine learning success stories often have one thing in common: they use methods that scale gracefully with ever-increasing amounts of data.

This is particularly clear from recent advances in sequence modeling, where simply increasing the size of a stable architecture and its training set leads to qualitatively different capabilities.1

Meanwhile, the situation in reinforcement learning has proven more complicated.

While it has been possible to apply reinforcement learning algorithms to large–scale problems, generally there has been much more friction in doing so.

In this post, we explore whether we can alleviate these difficulties by tackling the reinforcement learning problem with the toolbox of sequence modeling.

The end result is a generative model of trajectories that looks like a large language model and a planning algorithm that looks like beam search.

Code for the approach can be found here.

The Trajectory Transformer

The standard framing of reinforcement learning focuses on decomposing a complicated long-horizon problem into smaller, more tractable subproblems, leading to dynamic programming methods like $Q$-learning and an emphasis on Markovian dynamics models.

However, we can also view reinforcement learning as analogous to a sequence generation problem, with the goal being to produce a sequence of actions that, when enacted in an environment, will yield a sequence of high rewards.

Taking this view to its logical conclusion, we begin by modeling the trajectory data provided to reinforcement learning algorithms with a Transformer architecture, the current tool of choice for natural language modeling.

We treat these trajectories as unstructured sequences of discretized states, actions, and rewards, and train the Transformer architecture using the standard cross-entropy loss.

Modeling all trajectory data with a single high-capacity model and scalable training objective, as opposed to separate procedures for dynamics models, policies, and $Q$-functions, allows for a more streamlined approach that removes much of the usual complexity.

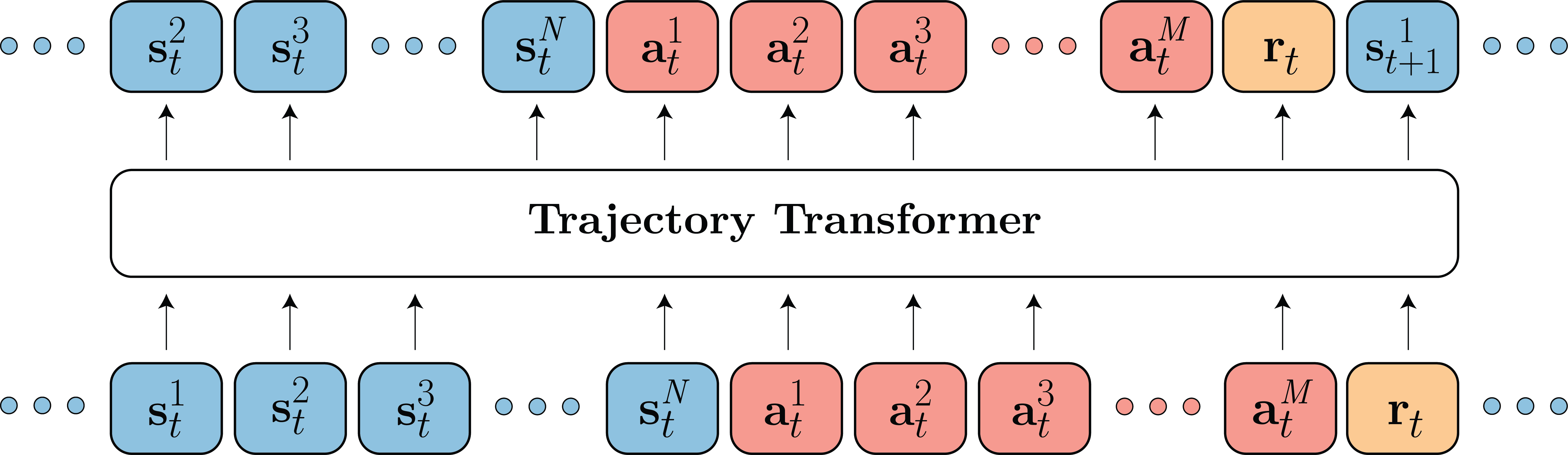

We model the distribution over $N$-dimensional states $mathbf{s}_t$, $M$-dimensional actions $mathbf{a}_t$, and scalar rewards $r_t$ using a Transformer architecture.

Transformers as dynamics models

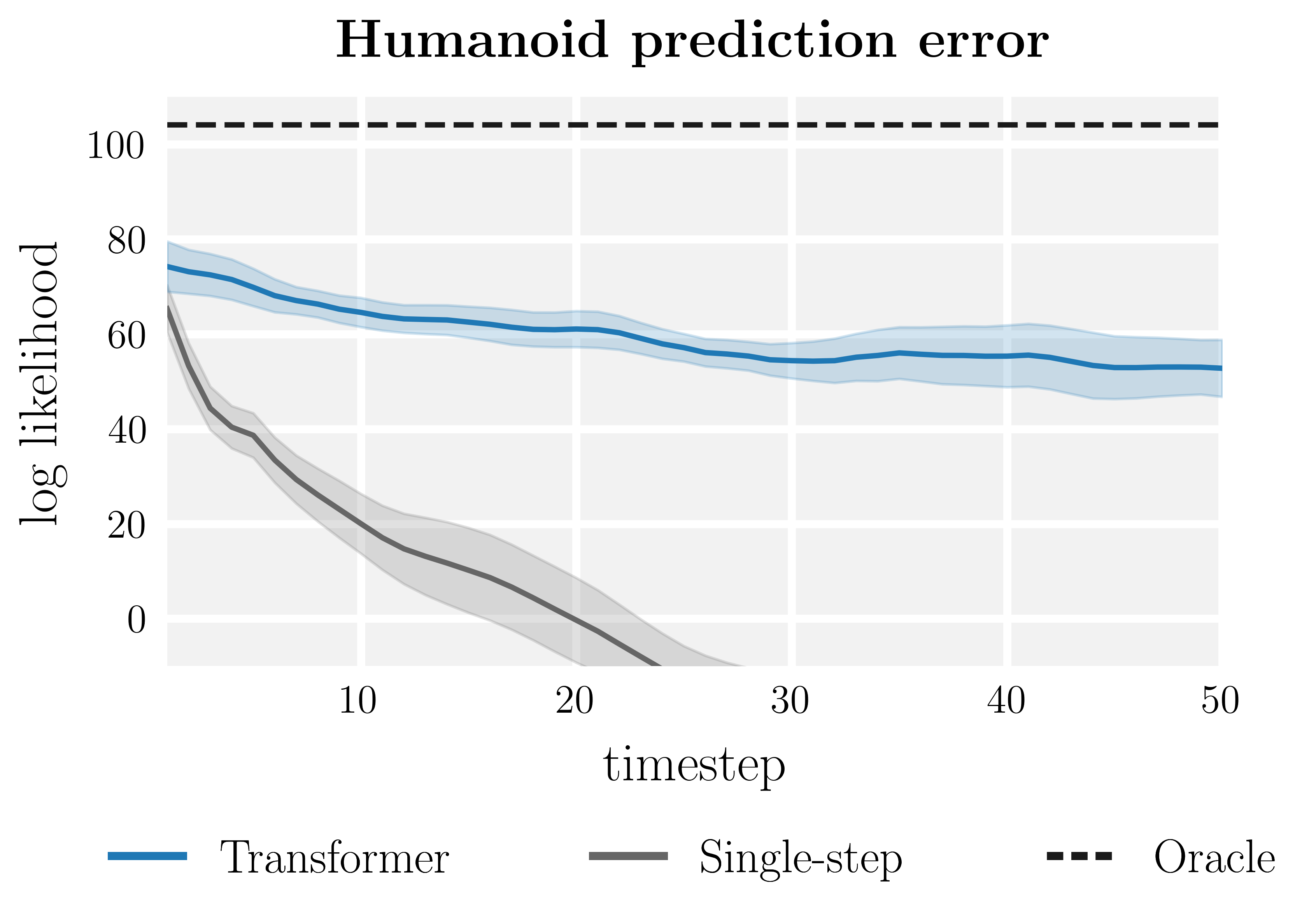

In many model-based reinforcement learning methods, compounding prediction errors cause long-horizon rollouts to be too unreliable to use for control, necessitating either short-horizon planning or Dyna-style combinations of truncated model predictions and value functions.

In comparison, we find that the Trajectory Transformer is a substantially more accurate long-horizon predictor than conventional single-step dynamics models.

|

Transformer Single-step  |

|---|

Whereas the single-step model suffers from compounding errors that make its long-horizon predictions physically implausible, the Trajectory Transformer’s predictions remain visually indistinguishable from rollouts in the reference environment.

This result is exciting because planning with learned models is notoriously finicky, with neural network dynamics models often being too inaccurate to benefit from more sophisticated planning routines.

A higher quality predictive model such as the Trajectory Transformer opens the door for importing effective trajectory optimizers that previously would have only served to exploit the learned model.

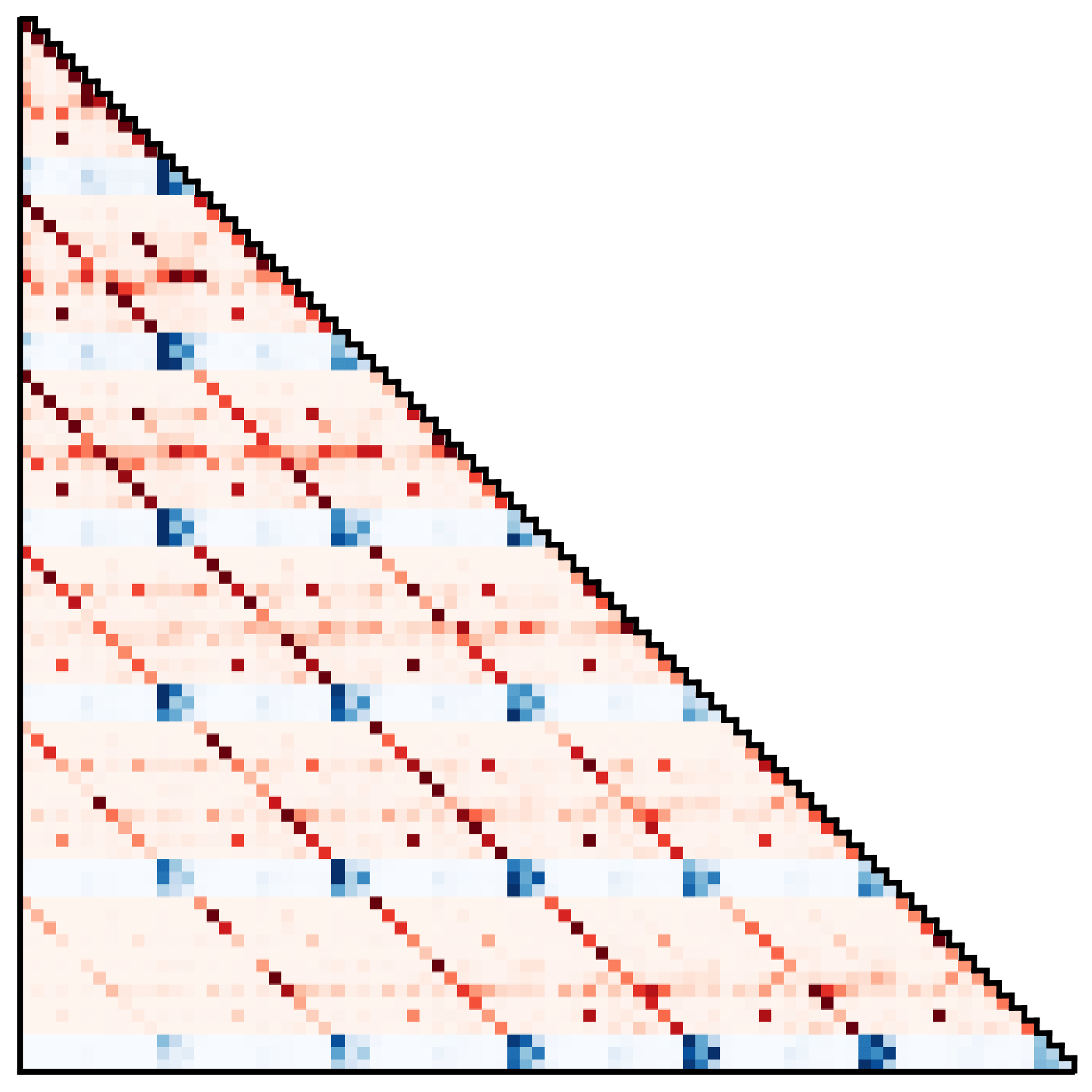

We can also inspect the Trajectory Transformer as if it were a standard language model.

A common strategy in machine translation, for example, is to visualize the intermediate token weights as a proxy for token dependencies.

The same visualization applied to here reveals two salient patterns:

Attention patterns of Trajectory Transformer, showing (left) a discovered Markovian stratetgy and (right) an approach with action smoothing.

In the first, state and action predictions depend primarily on the immediately preceding transition, resembling a learned Markov property.

In the second, state dimension predictions depend most strongly on the corresponding dimensions of all previous states, and action dimensions depend primarily on all prior actions.

While the second dependency violates the usual intuition of actions being a function of the prior state in behavior-cloned policies, this is reminiscent of the action smoothing used in some trajectory optimization algorithms to enforce slowly varying control sequences.

Beam search as trajectory optimizer

The simplest model-predictive control routine is composed of three steps: (1) using a model to search for a sequence of actions that lead to a desired outcome; (2) enacting the first2 of these actions in the actual environment; and (3) estimating the new state of the environment to begin step (1) again.

Once a model has been chosen (or trained), most of the important design decisions lie in the first step of that loop, with differences in action search strategies leading to a wide array of trajectory optimization algorithms.

Continuing with the theme of pulling from the sequence modeling toolkit to tackle reinforcement learning problems, we ask whether the go-to technique for decoding neural language models can also serve as an effective trajectory optimizer.

This technique, known as beam search, is a pruned breadth-first search algorithm that has found remarkably consistent use since the earliest days of computational linguistics.

We explore variations of beam search and instantiate its use a model-based planner in three different settings:

-

Imitation: If we use beam search without modification, we sample trajectories that are probable under the distribution of the training data. Enacting the first action in the generated plans gives us a long-horizon model-based variant of imitation learning.

-

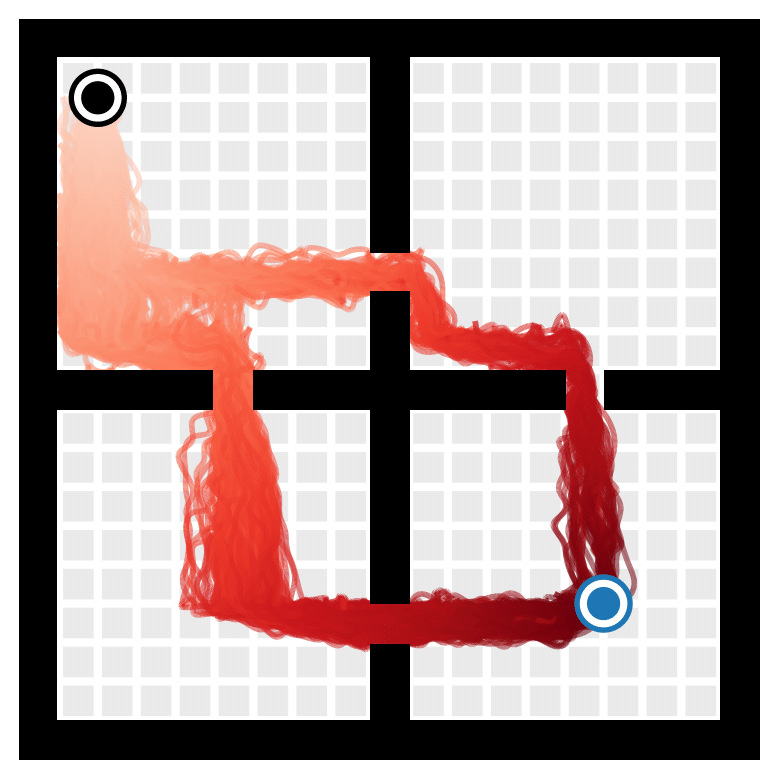

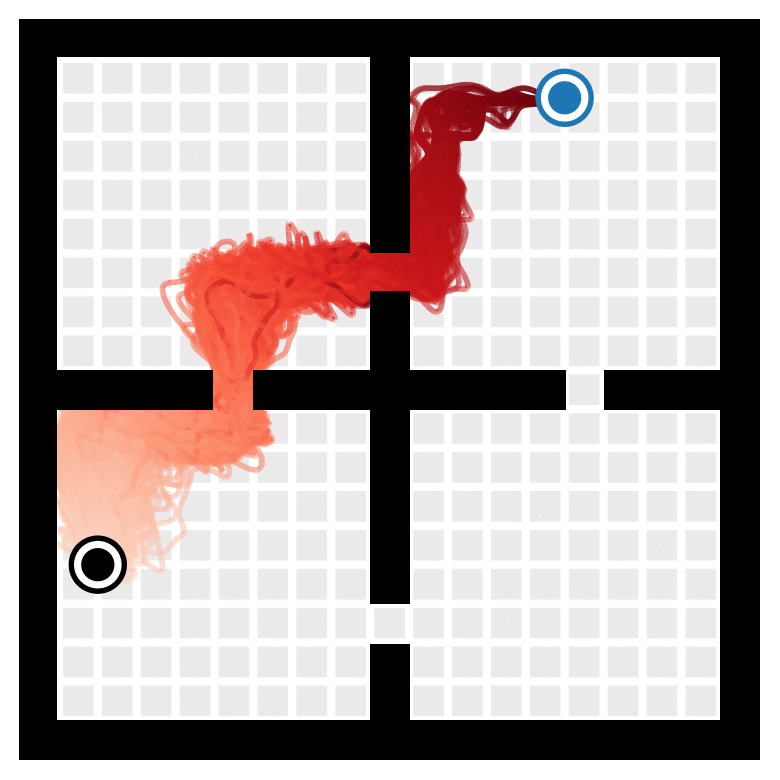

Goal-conditioned RL: Conditioning the Transformer on future desired context alongside previous states, actions, and rewards yields a goal-reaching method. This works by recontextualizing past data as optimal for some task, in the same spirit as hindsight relabeling.

Start

Goal

Paths taken by the goal-conditioned beam-search planner in a four-rooms environment.

-

Offline RL: If we replace transitions’ log probabilities with their rewards (their log probability of optimality), we can use the same beam search framework to optimize for reward-maximizing behavior.

We find that this simple combination of a trajectory-level sequence model and beam search decoding performs on par with the best prior offline reinforcement learning algorithms without the usual ingredients of standard offline reinforcement learning algorithm: behavior policy regularization or explicit pessimism in the case of model-free algorithms, or ensembles or other epistemic uncertainty estimators in the case of model-based algorithms. All of these roles are fulfilled by the same Transformer model and fall out for free from maximum likelihood training and beam-search decoding.

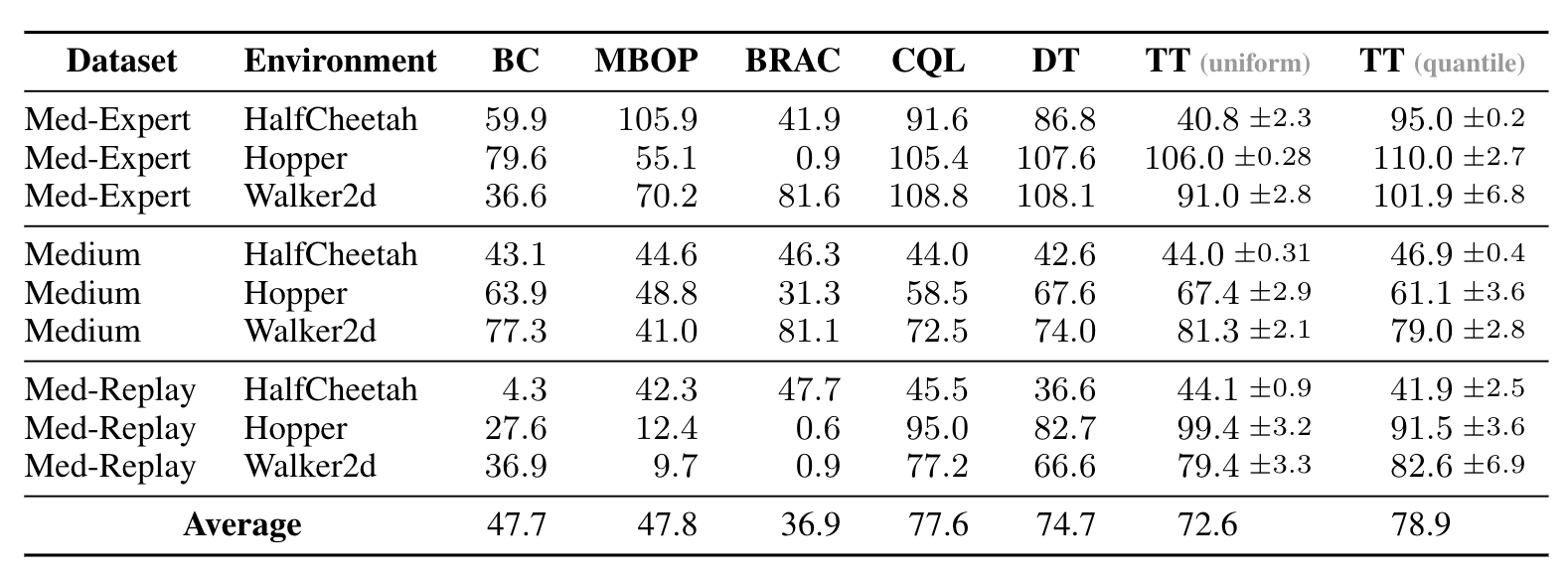

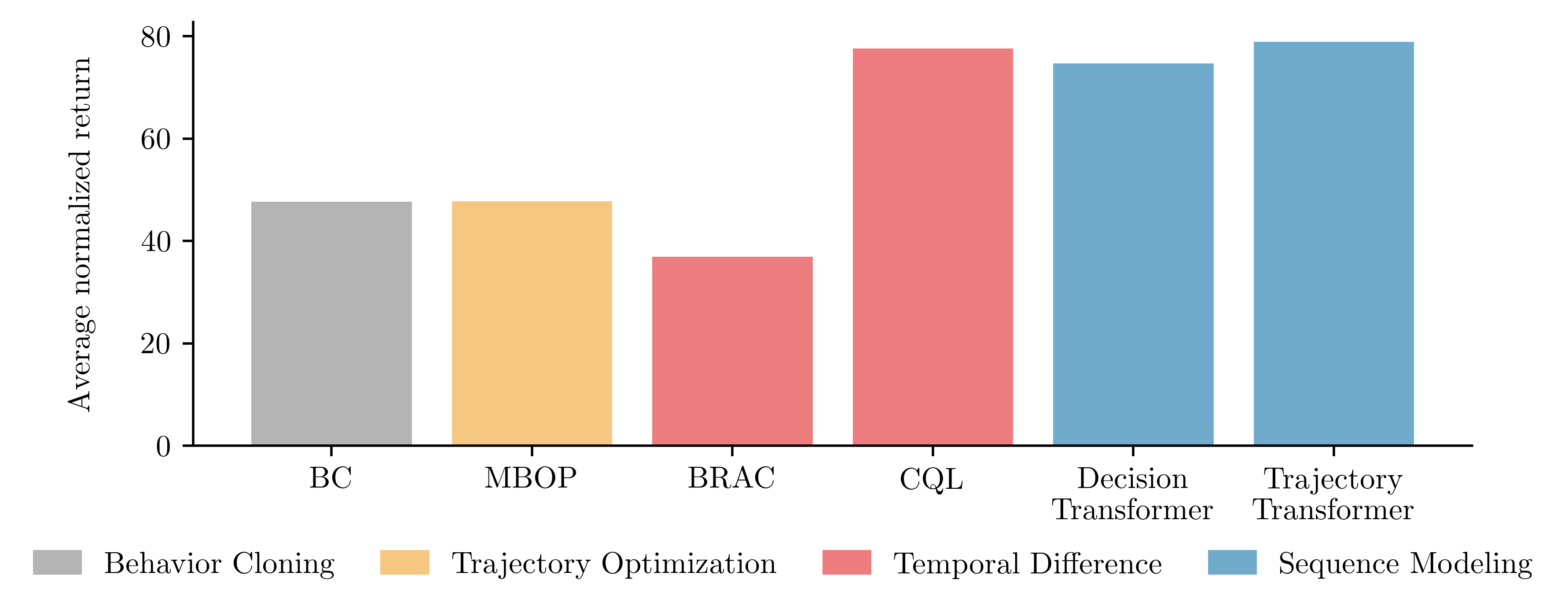

Performance on the locomotion environments in the D4RL offline benchmark suite. We compare two variants of the Trajectory Transformer (TT) — differing in how they discretize continuous inputs — with model-based, value-based, and recently proposed sequence-modeling algorithms.

What does this mean for reinforcement learning?

The Trajectory Transformer is something of an exercise in minimalism.

Despite lacking most of the common ingredients of a reinforcement learning algorithm, it performs on par with approaches that have been the result of much collective effort and tuning.

Taken together with the concurrent Decision Transformer, this result highlights that scalable architectures and stable training objectives can sidestep some of the difficulties of reinforcement learning in practice.

However, the simplicity of the proposed approach gives it predictable weaknesses.

Because the Transformer is trained with a maximum likelihood objective, it is more dependent on the training distribution than a conventional dynamic programming algorithm.

Though there is value in studying the most streamlined approaches that can tackle reinforcement learning problems, it is possible that the most effective instantiation of this framework will come from combinations of the sequence modeling and reinforcement learning toolboxes.

We can get a preview of how this would work with a fairly straightforward combination: plan using the Trajectory Transformer as before, but use a $Q$-function trained via dynamic programming as a search heuristic to guide the beam search planning procedure.

We would expect this to be important in sparse-reward, long-horizon tasks, since these pose particularly difficult search problems.

To instantiate this idea, we use the $Q$-function from the implicit $Q$-learning (IQL) algorithm and leave the Trajectory Transformer otherwise unmodified.

We denote the combination TT$_{color{#999999}{(+Q)}}$:

Guiding the Trajectory Transformer’s plans with a $Q$-function trained via dynamic programming (TT$_{color{#999999}{(+Q)}}$) is a straightforward way of improving empirical performance compared to model-free (CQL, IQL) and return-conditioning (DT) approaches.

We evaluate this effect in the sparse-reward, long-horizon AntMaze goal-reaching tasks.

Because the planning procedure only uses the $Q$-function as a way to filter promising sequences, it is not as prone to local inaccuracies in value predictions as policy-extraction-based methods like CQL and IQL.

However, it still benefits from the temporal compositionality of dynamic programming and planning, so outperforms return-conditioning approaches that rely more on complete demonstrations.

Planning with a terminal value function is a time-tested strategy, so $Q$-guided beam search is arguably the simplest way of combining sequence modeling with conventional reinforcement learning.

This result is encouraging not because it is new algorithmically, but because it demonstrates the empirical benefits even straightforward combinations can bring.

It is possible that designing a sequence model from the ground-up for this purpose, so as to retain the scalability of Transformers while incorporating the principles of dynamic programming, would be an even more effective way of leveraging the strengths of each toolkit.

This post is based on the following paper:

-

Offline Reinforcement Learning as One Big Sequence Modeling Problem

Michael Janner, Qiyang Li, and Sergey Levine

Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2021.

Open-source code

-

Though qualitative capabilities advances from scale alone might seem surprising, physicists have long known that more is different.

↩ -

You could also enact multiple actions from the sequence, or act according to a closed-loop controller until there has been enough time to generate a new plan.

↩